When analysing hedge funds, many investors have questions, or concerns, which are beyond the ability of traditional forms of hedge fund research. While many of these questions look to address aspects of risk management and mitigation, investors are now seeking more quantitative measures which can differentiate a fund’s strategy, risk and returns from those of its competitors, be they conventional peers within the same strategy bucket or indeed peers the manager themselves may not be aware of.

Rather than relying on analytics which look backwards, investors are increasingly looking forwards, worried about the possible future properties and behaviour of funds, about potential future returns and future risks.

In this article, I wanted to provide some insights for forward-looking investors (and managers) that might further inform their analysis of funds. I used Axicorda’s Aulexo technology and consulting platform to investigate the main industry strategy benchmarks through simulation: the objective being to cast some light on different aspects of what investors might be able to expect from these strategies in the next five years.

“Simulation is not prediction, but it is a powerful and flexible technique for exploring different future scenarios of a fund’s possible performance and risk, and provides a useful complement to traditional, retrospective analytics,” says Grant Fuller, co-founder of Axicorda.

The distinction between simulation and prediction is an important one: rather than providing a single, clear statement of the future (as one would expect with prediction), simulations provide a large number (in our examples 50,000) of possible outcomes and provides an impression of the likelihood of the future rather than a prediction of it.

Of course, any simulation has assumptions about the future, and for this article Aulexo was asked to make assumptions that over a five-year period an individual fund’s manager would be seeking to adhere to a particular strategy or mandate, and the fund’s performance would be influenced by factors similar to those it has experienced in the past. This article’s fundamental assumptions are, therefore, derived from historical performance but as will be discussed later, these assumptions can be changed to explore a range of ‘what if’ scenarios an investor might be interested in.

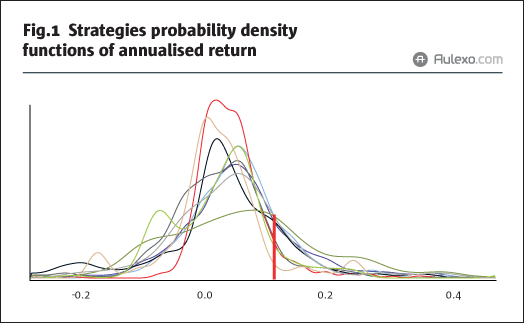

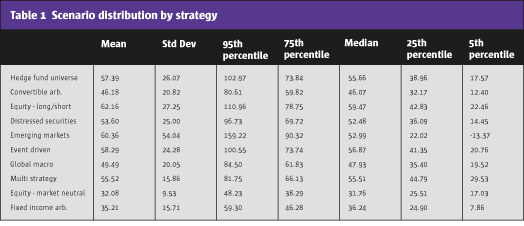

Applying these assumptions to a 60-month simulation of the hedge fund universe as a whole generates a diverse range of possible future outcomes (see Fig.1 and Table 1). This illustrates, based upon the assumptions discussed and the universe’s previous performance, a distribution of possible returns after an arbitrary time horizon of the next five years. For clarity, Aulexo was used to summarise the 50,000 scenarios showing the 5th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th and 95th percentiles, and based upon this the universe of funds provides a compelling picture for hedge fund allocation, with 95% of scenarios (or 95% confidence) generating returns above 17% in five years’ time, and 75% of scenarios (or 75% confidence) generating returns in excess of 38%.

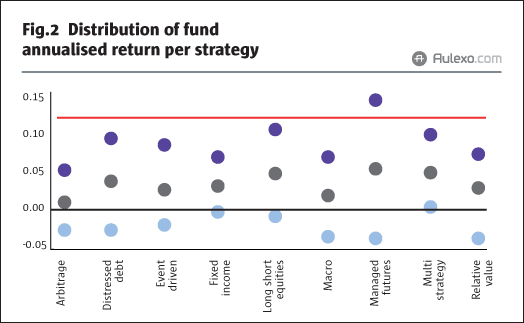

While this aggregate perspective will certainly be of interest to investors in hedge funds, greater insight comes from drilling down into the universe by strategy (and ultimately individual funds). Fig.2 illustrates the dispersal of possible returns from a five-year simulation for each strategy, and clearly shows Emerging Markets funds have much greater deviation in possible future returns compared to, for example, Multi-Strategy or Global Macro funds.

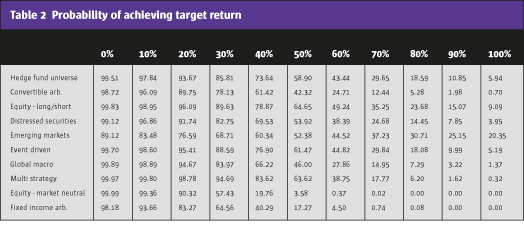

Further insights can be obtained from these simulations to aid both investors and fund managers. We can begin to explore strategies (and ultimately individual funds) in terms of target-return expectations and risk appetites over these five years. Questions that are reasonable for an investor to ask can now have a quantifiable answer and allow investors to compare strategies and funds against these new criteria. For example, it is reasonable to consider the likelihood that Distressed Securities, as a strategy, will exceed a target return of 30% during this five-year period, or how this compares with Fixed Income Arbitrage, as a strategy.

Table 2 shows 82.8% of simulations for Distressed Securities (as a strategy) produced a return in excess of 30% after five years, compared to 64.6% of scenarios for Fixed Income Arbitrage. Similarly, a minimum target return of 40% is mostly likely to be achieved by the Multi-Strategy universe of funds (83.6%), and least likely to be achieved by Equity Market Neutral funds (19.8%).

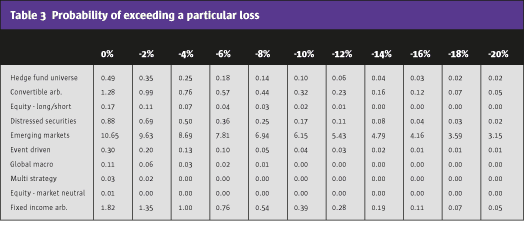

In addition to looking at potential gains, an investor might reasonably be interested in simulating the likelihood of losses associated with strategies (or funds). Table 3 illustrates this for Aulexo’s five-year simulation of the main strategies, and shows the three strategies least likely to experience losses over five years are Global Macro (0.11% of scenarios), Multi-Strategy (0.03%) and Equity Market Neutral (0.01%). Conversely, the three strategies most likely to experience losses greater than 10% are Convertible Arbitrage (0.32% of scenarios), Fixed Income Arbitrage (0.39%) and Emerging Markets (6.15%).

Earlier I drew attention to the assumptions that underpinned Aulexo’s simulations and while the analysis has not challenged these assumptions so far, the flexibility of simulation means the findings can be taken in new directions to explore various ‘what-if’ scenarios. For example, an investor could modify, or stress, simulation assumptions applied to a fund. Rather than simply applying conventional market metrics – e.g., the impact of a fall in the S&P 500 or the oil price – one could explore how long a fund may take to reach a total drawdown of 25%, or how great a drawdown might be expected from a sustained period of losses, for example, over a 12 month period? Here again, it is possible to quantitatively explore questions that previously have solely been the speculative remit of qualitative discussions between managers and investors.

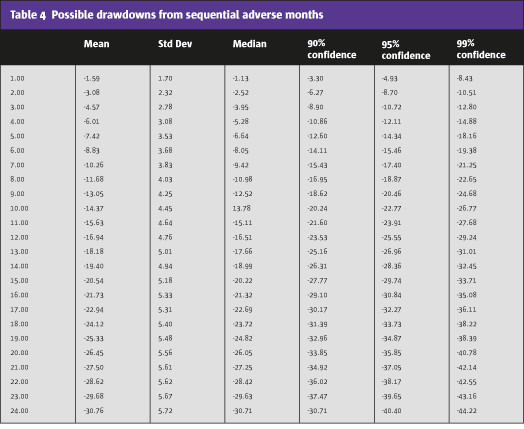

To illustrate this, I wanted to take a look at the effect disproportionate periods of sequential losses might have and to understand the likely drawdowns that might be expected from such adverse events. Table 4 shows the result of Aulexo’s simulations, inflicting the entire hedge fund universe with sequential losses. The results of these stress assumptions show, as would be expected, that as an ever-increasing number of months fail to generate positive returns, the drawdowns associated with these increase. Crucially, the simulations are able to quantitatively measure the magnitude of these drawdowns and provide investors the opportunity for a like-for-like comparison between funds.

However, the simulation can also improve understanding by providing insight into the possible distribution of scenarios. For example, should the hedge fund universe undergo sustained losses for a period of 12 months (similar to that experienced in late 2008), the mean drawdown is 16.9%, while 95% of scenarios did not have a drawdown larger than 25.6% and 99% of scenarios did not experience a drawdown greater than 29.2%. This additional level of quantitative detail helps investors grasp the relative merits and risks of any particular fund and also allows comparison between funds.

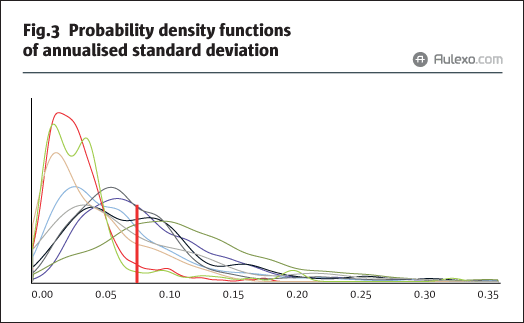

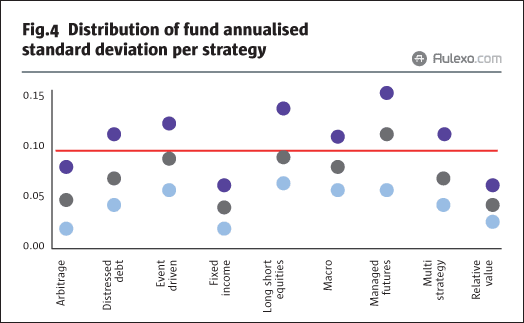

Having looked at possible scenarios associated with drawdowns, the next logical step would be to consider the ‘come back factor,’ namely how long would it take for a strategy, or fund to recover from a particular drawdown? Fig.3 illustrates the recovery rates for the hedge fund universe associated with some arbitrary drawdowns, and shows the probability (y-axis) of the universe recovering from the drawdown within a period of time (x-axis). The simulation shows there is a 50% chance that a fund will recover from a 15% drawdown within 18 months. Fig.4 extends this and allows a direct comparison of recovery rates for each of the main strategies associated with an arbitrary 15% drawdown.

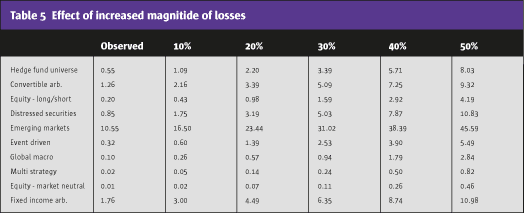

Another way to stress our simulations is to modify, or bias, the magnitude of losses. In this type of simulation, investors may be interested in understanding what future scenarios might look like if losses (or gains for that matter) were greater (or less) than had been observed historically. This type of stressed simulation is especially useful for emerging managers with limited performance history.

Table 5 shows the likelihood of each of our strategies incurring a loss as we increase the magnitude of historical losses by an arbitrary amount. For example, if the losses experienced by the Global Macro strategy were 20% greater than they have been historically, the simulation shows the number of scenarios incurring a loss after five years increases a little under six-fold, from 0.10% to 0.57%. By contrast, the same losses experienced by the Convertible Arbitrage strategy increase a little under three-fold from 1.26% to 3.39%.

By enhancing the potential losses, and biasing our assumptions of the future in this way, we have used Aulexo to provide funds with a statistically rougher ride and measured how we might expect them to respond. This can provide very useful data to assist in fund screening and selection, but also to help articulate and explain allocation between managers and, indeed, between strategies.

Apply these techniques to individual funds then, and a powerful new risk metric emerges, one that allows investors to leverage computationally-intensive calculations of past returns and performance figures and apply their own unique bias assumptions to shape and explore scenarios. The adoption of this technology is growing amongst the investor and manager communities.

“Investors are increasingly sophisticated as they look to uncover new opportunities and risks, and simulation provides some unique perspectives,” says Leah Cox, Managing Director of Apex Capital Introduction Services (ACIS), adding, “Managers are under significant pressure to demonstrate their uniqueness, their differentiation. Those with insights from simulation have a clear advantage, and ACIS work with investors and managers alike to help maximize their benefit from it.”

Axicorda’s Fuller agrees: “Use of simulation-based analytics has become part of the investor toolbox for fund screening, selection and monitoring as well as part of their quantitative due-diligence. Aulexo’s technology and consulting has been helping a wide range of investors and managers make the best use of these advances.”

While Fuller himself is quick to point out simulation is not prediction, it is reasonable to suggest that analytics of this nature provide investors and indeed managers with the statistical food for an interesting discussion, and can only help improve the quality and substance of dialogue between investor and manager.

A manager who can tangibly demonstrate his fund’s uniqueness and resilience under harsher market conditions has an additional selling point.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical