Financial markets have had a rather turbulent time in 2016 to date, to say the least. The nature of this volatility has been surprising and difficult to understand for many investors. In the early weeks of the year there were steep declines in the prices of many equities and corporate bonds, as concerns mounted over the significance and implications of falling commodity prices, especially for the financial system and the broader economy. There were clear echoes of the trauma of 2008, which made many investors fearing the worst. In combination with a move to negative official interest rates from a number of central banks, this dynamic was very supportive of government bonds, the “safety asset” of choice for many years now. Correspondingly, sovereign bond yields in the larger developed economies fell sharply, and made new lows in many cases.

From mid-February, there was a quite dramatic and equally surprising reversal of these asset price moves, with oil and resource assets leading the way, and emerging market currencies appreciating. Not all prices have recovered completely, but there has been a quite remarkable change in investors’ perception of risk. Again, the precise rationale for this recovery is far from clear, especially if looking for explanations based on improving economic or corporate data.

So now, it would appear, we are in a position where some sense of calm has been restored. This calmness has, however, what RBA Governor Glenn Stevens referred to as a certain ‘eeriness’ about it, and feels fragile. The reality is that the concerns that investors focused on in the early part of the year remain largely unresolved. In addition, these phases of turbulence are highly unsettling, and can have a negative impact on psychology that persists for an extended period, leaving investors nervous and with fickle emotions and beliefs in which they have little conviction. This suggests volatility could easily re-emerge.

Furthermore, there are significant macroeconomic policy questions that remain unanswered, and there is a sense that we could be approaching an ideological crossroads in several key economies. Discussions around “helicopter money” and “limits to monetary policy” highlight this. The uncertainty about which path will be taken and whether there is divergence in policy solutions between economies is also damaging to market confidence. This has played a role in most of the recent phases of volatility and nervousness, and it is likely that it will again in the period ahead.

These “episodes” in market behaviour, which have occurred rather frequently in recent years, highlight the important role that human behaviour and emotions play in asset price determination. The analysis and understanding of the human element in market behaviour is something on which we have focused for a very long time, and is right at the heart of our investment thinking. Accordingly, our market views are always couched in terms of an assessment of how emotions and human biases have impacted the pricing and valuation of assets, and whether such impacts are likely to persist or change course over time.

What we observe is that rapid price action, of both a positive and negative nature, provokes a powerful emotional response from investors. In good times, joy and euphoria have a strong impact on people’s confidence, their perceptions of their own knowledge and skills, and their attitudes towards risk. For those not participating, or on the wrong side of things, the stigma of being wrong, jealousy and envy, or an irritation about having missed out, produce lower self-esteem and embarrassment. Phases of negative returns and performance have an obvious opposite impact on people and, because of the asymmetry in how we feel losses more than gains, these phases can be deeply and more profoundly traumatic. Shorting can change these emotions, but not necessarily in a helpful manner!

Our thesis is, that it is this emotional dynamic of the investing experience that leads to many of the wild movements seen in markets, and that shifts in how investors actually feel about taking risk can drive valuations to extreme levels, swamping economic fundamentals on which most investors seem to focus almost exclusively.

So, if we are right about this, how would we assess the emotional make-up of investors today and what signals would we look at?

A quick look at a range of conventional valuation metrics instantly reveals the current situation as being unusual, and quite extreme, relative to longer run history, or a sense of what we might normally see. It suggests that within the investor community, there prevails a deep scepticism and pessimism about the durability of economic growth and future returns on capital, with a resulting preference for assets with higher degrees of certainty about a return of capital over those with some degree of hope of future growth. In addition, investors continue to exhibit a myopic focus on the desire to avoid volatility and the risk of short-term loss with an intensity that did not exist in earlier decades. This aversion to short-term loss and volatility is prioritised over the potential for material upside and strong positive returns. There has always been a tension between these goals, but it seems today that investors in aggregate now view low volatility as the latest “holy grail” and are willing to sacrifice the possibility of stronger returns in order to achieve it. Both theory and history tell us that this situation will change – eventually!

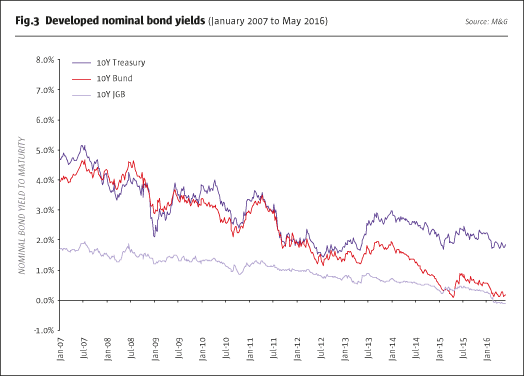

This preference for “safety” and capital preservation manifests itself clearly in the very low or even negative yields on sovereign bonds in many economies. Investors have significantly reduced the rates of return they require to lend money to governments, as inflation behaviour and growth concerns have prompted central banks to maintain official interest rates at levels close to or below zero. In the last year or so, these rates of return have fallen below zero, with investors effectively paying for the privilege of lending money to governments; something most people saw as highly improbable only a year or so ago.

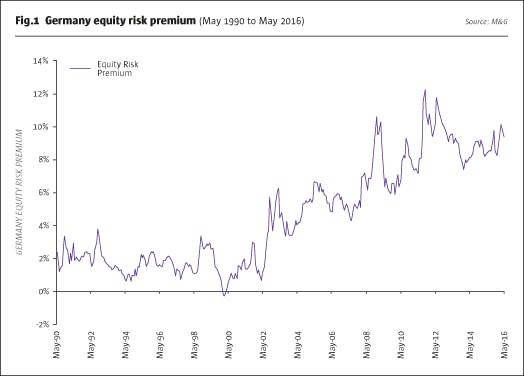

The flip side of extremely low levels of return on cash and “safety” assets is elevated prospective returns on “risky” assets. It is no surprise, then, that selected equities and corporate bonds sit at valuations that look more normal or even abnormally attractive. This is especially true ofthose assets in sectors or industries that have seen stress, or are seen as vulnerable to a weaker global growth environment. The equity risk premium and credit spreads over “safety” assets look elevated in many cases. Lower yields on higher quality or more secure equities and corporate bonds further emphasise the point.

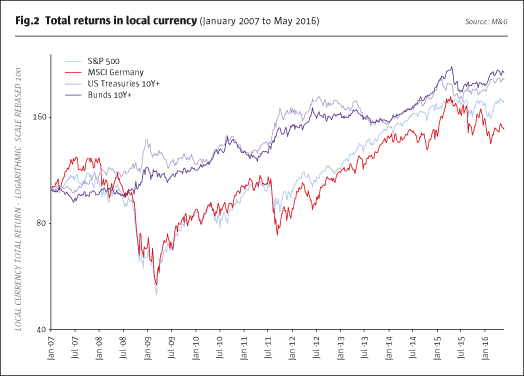

It is worth pointing out however that in the post-2008 environment, this “volatility averse” behaviour has not been an expensive behavioural trait. In fact, it has proved highly profitable to maintain a cautious or negative view, so long as this has manifested itself in a tendency to own exposure to sovereign bonds of longer duration. Interestingly, a cautious perspective that was represented merely by shorting, or avoiding equity, has not been beneficial. This simultaneous strong performance from both bond and selected developed equity markets has been a surprise and a source of much confusion.

So, biasing portfolios towards being long of government bonds has been a rewarding strategy since 2009. Longer-dated bonds in the US, Europe and Japan have produced substantial multi-year capital gains of the type more often associated with riskier assets such as equities, as yields have trended lower. In addition, they have continually behaved like insurance policies, as they have responded most positively in phases of stress for risk assets, thereby cushioning portfolios in downdrafts.

This pattern of behaviour has been hugely beneficial to portfolios that have had a pro-bond disposition. Importantly though, the magnitude and durability of this phase has been a surprise to most, including those who have benefited from it! More importantly, the reality is that this a finite game. Strong capital gains from bonds come at the expense of future returns – as yields fall, prospective returns decline as you effectively take some of the future returns up front.

Interestingly, from a behavioural perspective, it never “feels” like that. The satisfaction resulting from gains associated with a transition to lower future returns can distract investors and cause them to want to continue to enjoy the journey, even if they actually know it to be unsustainable! This emotional dynamic has been very clear in this latest phase. Discussion about “bond bubbles” and an expectation of an imminent “great rotation” have become strangely absent, especially given how mainstream they were in the recent past. Indeed, many investors appear to have forgotten that they even discussed the ideas.

These dynamics have intensified in the last twelve months as we have witnessed a capitulation on the idea that economies will return to “normal” some time soon, and that they “will get out of the woods”. In the period since 2009, this sub-conscious or neutral assumption that things would go back “to how they were before” underpinned investors’ economic forecasts and their interest rate and corporate profit assumptions. This assumption was the “path of least resistance” option for most investors attempting to assess the medium-term economic outlook. Importantly, a sense of “normal” was characterised by the type of conditions that prevailed, and “how things felt” prior to 2008. It persisted, in spite of ongoing disappointment in certain economies, as markets assumed that the inevitable had been merely delayed and that the recovery process was just taking longer than usual.

By early 2016, however, this sense of “getting out of the woods” and the certainty of an eventual return to “normal” had shifted. Discussion of secular stagnation, the limits to the effectiveness of monetary policy, and the burden of debt at the global level are all a reflection of a gradual, or occasionally marked erosion in confidence about a return to higher levels of economic growth. For many commentators and investors there is a concern that a sense of “normal” should shift to an expectation of a continuation of the recent weaker economic situation and trends. There is a suspicion that this might be “as good as it gets” – unless some more profound macro and microeconomic policy changes are forthcoming.

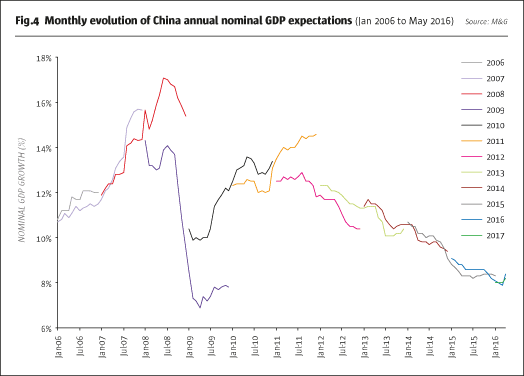

This deterioration and erosion in confidence in global economic growth can be seen in consensus forecasts. There has been a marked reduction in expectations for growth into the medium term over the last 12 months. This extends to expectations for the longer run as well. Some of this is a reduction in forecasts for real economic growth, but importantly, some of it is a function of lower inflation expectations. The combination has produced a significant decline in expectations for nominal GDP, as can be seen in Fig.4. This is significant for profits, interest rates and concerns over debt levels.

So where does all of this leave us as we assess the investment landscape and the outlook for returns from here?

Our assessment is that we have arrived at a pivotal and potentially critical moment in time, where a material change in investor thinking and behaviour is needed. The reality is that with valuations at current levels, a continuation of existing attitudes and behaviour is highly likely to lead to disappointing and possibly very negative nominal and real returns. The strategies that have been successful for the last decade are now destined to struggle. As ever, conclusions such as these, based on valuation signals as they are, do not tell us much about the immediate future. It is possible that current behaviours persist or even intensify, with valuations becoming even more extended. We have seen similar things before, where valuations become highly stretched and investors suspend all normal beliefs about the pricing of risk. Ultimately, though, gravity re-asserts itself and the results can be disastrous. We believe the time is near.

Given the evolution of economic beliefs towards a much more negative, concerned view of the world, together with the elevated levels of return on offer for various “riskier” assets, the most appropriate strategy must surely be to take on and accept some of the volatility associated with these assets and avoid exposure to “safer”, less volatile assets. Valuations suggest that these riskier assets are the only ones capable of delivering attractive real returns on a sustained basis. Additionally, a willingness to short some of the “safe haven” assets that have provided such an enjoyable experience in recent years, whilst emotionally challenging, is something that ought to be at the front of investors’ minds.

This perspective relies on our long-held belief that volatility is not equal to risk. In our view, true risk is a function of the possibility of more protracted or permanent loss. We believe that the current obsession with volatility is counter-productive and misses the point about what actually matters on a multi-year view. Owning assets that have in the past delivered good returns and had attractive risk characteristics but now stand at valuations that imply this cannot be repeated, is a very dangerous strategy.

We believe that many of the negative economic arguments are now well rehearsed, and that we would need to see far more problematic outcomes to offset the impact of more attractive valuations. These are, of course, possible but, then again, so are more positive outcomes, which could have a dramatic impact on markets, given prevailing valuations.

So to conclude, it is our belief that volatility aversion, extrapolation of recent abnormal trends and a significant deterioration in economic beliefs have produced a valuation mis-alignment and an extreme dis-equilibrium in market pricing that have taken us to a pivotal moment. This situation could yet persist or intensify, but we strongly believe it will correct and will produce significant surprises when it does. In order to exploit this situation, investors must change course and focus less on short-run volatility, and more on sustainable attractive returns. They will also need to embrace the idea of ownership and exposure to assets that have been viewed as “risky” and not attractive as part of alternative investment strategies. This may feel uncomfortable and emotionally challenging, but we believe the payoffs for doing so will prove highly worthwhile. The costs of not changing course could be significant.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

A Pivotal Moment?

Assessing the emotional make up of investors

DAVE FISHWICK, CIO, MACRO INVESTMENT BUSINESS, M&G INVESTMENTS

Originally published in the issue