“I am still hearing the same complaints,” bemoans Amundi Alternative Investments’ new deputy CEO and head of Business Development, Michael Hart (pictured above), who THFJ met at the firm’s City of London offices. The grumbles are about client servicing, responsiveness and client reporting – at hedge fund managers – where Hart is well qualified to gauge client sentiment. Over his 11 years as a founding partner of investment consultant bfinance, Hart sat through thousands of presentations and lent his ear to hundreds of pension funds and many sovereign wealth funds. “Many hedge funds that want to be viewed as mainstream have upped their game and become institutional, but most are not at the same level as long only where we rarely hear complaints,” Hart judges, and he reckons long-only managers have an advantage as their more extensive experience has given them more time to hone their skills.

Modular client reporting

But Hart has no sympathy with those who have not raised their game to the requisite level. “Client servicing is the one and only area where you have complete control so there is no excuse for sending out late or incorrect data,” he insists, and goes on to admonish those managers who churn out the same “one-size-fits-all data dump” for all clients. Although some regulators and some consultants are pushing for standardization – through AIFMD leverage calculations or the Open Protocol Enabling Risk Aggregation for instance – Hart maintains that client reporting should be granular enough to offer “a modular level of reporting tailored to the audience and the user.” Hart’s close discourse with pension fund trustees continually recurs in our conversation, and they are a group that require a more accessible format for reporting.

Fortunately Hart has been “pleasantly surprised that Amundi reporting is modular enough to take account of the end user” – and credit for this goes to head of Marketing and Client Servicing, Sophie Dupuy, who has been developing the reporting at Amundi for eight years. In his eight months at Amundi since November 2014, Hart has already ascended a steep learning curve, discovering that internal clients can be very technical and demanding, but reports designed perhaps for French rocket scientists, are not foisted upon different clients who may be content with a bigger-picture level of reporting. Having seen the best and worst of client reporting over his career – which recently included stints at managed account platform Sciens and at Aberdeen Asset Management – Hart has a clear vision of what hedge funds must do to win and retain more business.

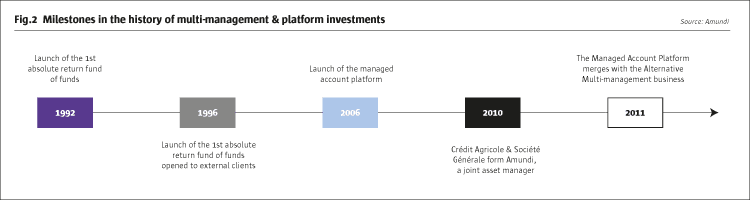

One ingredient is providing appropriate portfolio transparency. Amundi takes pride in a culture of transparency around its Managed Account Platform (MAP) – but this is attuned to hedge funds’ sensitivities over the use of confidential data. “We always ask end users where the data will go,” stresses Hart, and although Amundi itself naturally has full, position level, portfolio transparency, this is not passed on to clients. “We have to simplify everything for clients and less sophisticated investors so the data gets aggregated in accordance with what the client wants,” he explains. MSCI RiskMetrics does produce a batch of standard reports, but Amundi manipulates the package to generated dedicated reports for specific clients. This is nothing new for Amundi, which has always customized everything for in-house mandates for corporate parent and 80% owner Credit Agricole (CA), and other CA entities, recalls Dupuy, who thinks that Amundi obtained an early mover advantage, from having “entered the MAP business in 2005, which was very early compared with other players.” She harks back even further to the origins of Amundi’s hedge fund business in the early 1990s, when customization capabilities were part of the DNA from the start. Amundi’s MAP was originally created to support its structured investment solutions business and its structure appeals to insurers today. Amundi’s look-through transparency permits the construction of risk-aggregated reports that help insurers to economize on their Solvency 2 risk weightings, which dis-incentivizes insurers from allocating to opaque funds.

Customized investment mandates

The data can be sliced and diced over any axes. Recently a Korean institution wanted a specific reporting focus on exposure to Asia, and this was not a problem for Amundi, which also customizes investment mandates, finding it “easy to carve out and exclude certain sectors or stocks for specific mandates,” Hart says. The Alternatives business benefits from synergies with the experience of giant long-only unit at Amundi – Europe’s largest asset manager, with assets of €954 billion as of the end of June, making it the only European asset manager belonging to the world’s largest 10. Amundi Alternative Investments is a specialist investment centre of Amundi, running just over $8 billion, (as of the end of June), with separate staff, but knowledge transfer from Amundi’s 30 global offices can be useful for to garner insights from the wealth of macroeconomic research inside Amundi, and for tailoring investment strategies.

Amundi has four business units (shown in Table 1) that the company describes as a “One-Stop Shop”: the Managed Account Platform, Open Ended Fund of Funds, Dedicated Mandates and Advisory. Hart recognizes that this offering is competing with the large investment consultants, including his former firm, that also cover hedge funds but he thinks “the size of our teams and the length of our experience gives us an edge over the consultants.” The Amundi Alternative Investments team contains nine on investment due diligence, three in each of portfolio management and operational due diligence, four in risk management, and one in quantitative research, adding up to 16 investment professionals (with the total Amundi Alternative Investments headcount numbering around 55). Some of the team have been acclaimed – the chief investment officer of Amundi Alternative Investments, Sylvie Dehove, was selected as one of The Hedge Fund Journal’s “Leading 50 Women In Hedge Funds” in the biannual 2015 survey sponsored by EY, while Amundi’s head of Equity and Event Strategies Jeannine Daniel, recently hired from Kedge, was recognised in the annual Financial News “40 Under 40” Hedge Fund Awards in 2014. Amundi has been augmenting the team for some time, and Hugh Burnaby-Atkins was recruited in 2013 as a director of Hedge Fund Manager Search and Selection for fixed income, credit, convertible, distressed debt, structured credit and volatility strategies. Having historically been split between Chicago, New York and London, hedge fund research has been centralized in London since 2013 as Hart says it is easier for consultants to meet all of the staff at one location.

Consultants who rate Amundi are of course both appraising the firm and potentially competing with it, but Hart does not feel threatened by this. He acknowledges that Amundi should learn from the consultants’ success in listening to client concerns and tailoring portfolios. Tail-risk protection mandates are one example of what could be offered, but Amundi is ultimately “agnostic as to what the client wants,” says Hart, who wants to ensure that “clients can make the most fully informed decision, in their interests.” Hart is not necessarily wedded to hedge funds – “we always look at best of breed and would look at other products such as ETFs if we found net-of-fees performance was better. In fact, these products are marginally used for overlay purposes. We aretrusted advisors with no conflicts or potential conflicts,” he says.

On fees, customization (of advisory, dedicated mandates or the MAP) can lead to different fee structures, whether Amundi is advising advisory clients on how to negotiate fees or devising structures for the dedicated mandates or the MAP. Here Hart still sees some pressure on hedge fund fees, but he puts this into the context of “pressure on fees for active management across the board, including for long-only managers.” But he does find that more experienced trustees involved with larger pension schemes are more willing to accept hedge fund fees. And concerns may have migrated from the level of fees to their structure. Hart reports pension funds in Australia and the Middle East accept hedge fund management fees, but are seeking modifications to the periodicity of performance fees. Apparently funds accustomed to a rolling three-year performance fee on the long-only side may balk at being asked to lock in a calendar year performance fee in year one, after which performance may reverse. “Deferrals and clawbacks are sought after to mitigate the potential for a great year followed by a give back,” he says.

Managed account platform differentiators

Advisory services, or dedicated portfolio mandates are sufficient for some clients. But either of these can also be the first stage in a dialogue that can result in clients allocating directly to the MAP, where the approach is also customized – “we are plug and play so a dedicated fund of one is fine,” says Hart, though the platform also offers comingled vehicles. Hart became familiar with all of the MAPs whilst at bfinance and Amundi’s MAP, which was created in 2005, has many differentiating features that appeal to Hart.

Operational Due Diligence (ODD) is prerequisite for Hart. Amundi had to pass muster on this and it did: “ODD has power of veto, which is very important and relatively rare in the industry,” according to Hart.

Deal-breakers for Amundi’s ODD teams could include business risk, insufficiently experienced fund directors, or an absence of independent fund directors for investments outside of the MAP. Background checks are the only part of the process that is outsourced, and here Amundi carries out “extremely thorough checks on key investment and business staff.” This gives potential clients “a huge degree of comfort,” says Hart, who also ascertained that Amundi’s MAP had never been a victim of fraud before he decided to join the firm. “We all need to sleep at night,” says Hart and the ODD process does not stop after investments are made.

Strict criteria on the investment as well as ODD side may explain why the MAP still houses just 23 funds, albeit up from 21 two years ago when THFJ last profiled Amundi. Hart claims the turnover of managers on the platform is low – as is the turnover of client assets per manager, although the platform facilitates seamless and simultaneous transfers between funds to help clients tactically rebalance allocations without having to await redemption proceeds or use bridge finance. Fig.1 shows how Amundi’s daily, weekly and monthly dealing vehicles are amenable to various styles of investing that can range from shorter-term, tactical rebalancing to longer-term, more strategic shifts in portfolios.

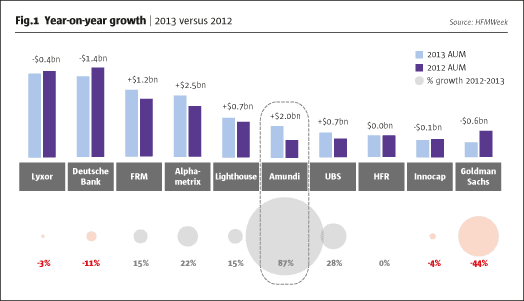

With $3.3 billion of assets as of the end of June, the MAP is ranked as the seventh largest but does not seem to aspire to be the biggest – quality rather than quantity is key. “Amundi’s MAP exists to serve clients and is not just a distribution platform,” says Hart. Investor demand is the driver of new funds, and the platform does not host empty shells opportunistically hoping to raise assets. Amundi’s clients and fund of funds always co-invest in funds so the majority of assets are internal and “our interests are completely aligned with those of external investors,” asserts Hart. The fact that Amundi staff also invest in the funds reassures the trustees that Hart talks to.

The business model is to charge a flat fee and Hart claims that one of the global investment consultants carried out a confidential global manager search and concluded that Amundi’s MAP had the lowest costs amongst a peer group of MAPs surveyed. Hart says that some managers on the platform will forego some of their own fees to accommodate Amundi’s layer of fees, so as to keep overall costs competitive.

Tracking error of MAP funds versus flagship or sibling funds/feeders from the same manager, can be a source of frustration for allocators – and negative tracking error can outweigh any savings on fees or costs. It is seldom straightforward to quantify any tracking error that may apply to feeders on Amundi’s MAP as some of the strategies have been customized to Amundi or client requirements. But Hart does know of one case where a client has migrated to Amundi from another platform that had far higher tracking error for particular managers.

Open architecture means that none of the 23 funds on the MAP, (nor the 60 on Amundi’s advisory buy list), are, or need to be, Amundi-managed products; though in theory they could be. Amundi has been running open-ended funds of hedge funds since 1992 and still offers comingled products such as Luxembourg AIF Amundi Absolute Return Harmony. This is a high conviction fund of funds allocated to between 15 and 20 “best of class” managers, with names including Pentwater, TIG, Paulson, Jana, Boussard & Gavaudan and Aristeia disclosed in its pitch book. All of these have to be drawn from Amundi’s advisory buy list of 60 funds and some of them are also on the MAP. This product comes under the alternatives unit but single-strategy Amundi funds in areas such as volatility arbitrage, macro and FX, containing the word “absolute” in the name are not part of Amundi Alternative Investments; nor are those Amundi products branded as “total return.”

Onshore only

Onshore domiciles are universal throughout Amundi Alternative Investments, which has been wholly onshore since 2012, and this has been driven by “demand from large institutions that want to be more regulated so that trustees feel more comfortable,” says Hart. He is acutely conscious of headline risk when talking to trustees, who are particularly sensitive to media coverage. Some trustees, including less experienced ones and those at smaller funds, “need to be constructively informed and educated, to have a realistic view that that hedge funds do have a place and can offer value for money,” he says, and being onshore helps.

Recently “a large private bank with no desire to go offshore approached Amundi because AIFMD appeals to them and their clients,” Hart explains, and he does think a lot of education is still required on AIFMD. Amundi became an AIFM in 2013 – seven months before the deadline – and is steadily adding marketing passports throughout Europe, focusing on countries where there is the most demand. “We are not going to passport if a country is not ready for hedge funds yet,” says Hart, once again illustrating the customized approach.

Presently the MAP is populated by AIFs (Alternative Investment Funds) as these afford sufficient flexibility for the full spectrum of hedge fund strategies. “AIFs can use the full range of investment instruments and do not face investment restrictions that apply to some fund structures,” says Dupuy. AIFs must disclose a leverage cap, which also has to be calculated in a prescribed manner, but AIFMD does not impose any over-riding ceiling on the level of leverage in the way that some fund structures can do, Dupuy adds. Nonetheless Amundi always has its ears to the ground and investors should watch this space for some possible UCITS launches in 2016, inspired by reverse enquires from European private banks. Adding UCITS could also allow Amundi Alternative Investments to raise more assets from retail investors, having hitherto focused mainly on institutions. Amundi Alternative Investments is not, however, jumping on the US mutual fund ’40 Act bandwagon, and the group no longer has a US presence; though many managers on the platform are US-based.

Global talent hunting

Hart began the interview with client reporting, which lies at the end of the investment process, and ended it with sourcing investment managers, at the start of the process. Customization is one source of differentiation, and Amundi’s relationships with leading hedge fund managers have also led to some unique offerings. “Our double-levered Paulson feeder is the only MAP product replicating the doubled-levered Paulson flagship fund,” says Dupuy, and this feeder won The Hedge Fund Journal’s 2014 award for “Best Performing Event Driven fund.” Two other Amundi funds were also honoured – the Amundi Alternative Investments TIG Arbitrage Associates Enhanced won the award for “best performing merger arbitrage” while the Amundi Alternative Investments Tremblant Long-Short Equity got the gong for being the “best performing long-short equity fund.” “We are very happy with the performance of these funds and they have been on the platform for a long while,” says Dupuy.

Paulson is the largest by assets on the platform and investors should not assume all funds have to be multi-billion in size to meet Amundi criteria. Amundi does not currently provide seed capital but will look at smaller-sized, mid-cycle managers, and may well set the assets bar somewhat lower than some big institutions. “Realistically we want to see at least a three-year track record and minimum assets of 300 million in a strategy,” says Hart and this is not an arbitrary number plucked out of thin air. It is simply a consequence of institutional investors’ dual desires to avoid being above 10% of a vehicle, and to put meaningful allocations to work. Given that most institutions want to allocate at least $25 million and don’t want to go over 8%, the $300 million is customized to these constraints. There is clear evidence that Amundi is sincere about allocating to smaller managers: in 2015 Amundi has on-boarded a medium-sized US manager: FrontFour Capital Group, which manages $500 million in an event-driven, small and mid-cap focused, equity and credit strategy it has run since 2006. Amundi is creating an AIFMD-compliant version of the strategy for the MAP.

Smaller and medium-sized managers in the US, such as FrontFour, are seeking marketing routes into what is being dubbed “Fortress Europe” in light of ESMA’s decision in July 2015 to initially restrict full third-country AIFMD passports to Switzerland, Jersey and Guernsey. Amundi is not mainly a distribution platform but the MAP may offer a solution that Hart thinks could be “much more cost effective from a regulatory and legal standpoint” and this is making it easier for Amundi to open dialogues with smaller managers outside the EU.

Many of the names mentioned are US-based but Boussard and Gavaudan, and indeed Brummer’s Lynx CTA, are European and Hart insists there is no preconceived geographic bent. “We have no bias to the US, Europe or Asia, we just want the best managers and so long as they have a robust setup it does not matter where they are based,” says Hart.

Strategy views

Event driven has been amongst Amundi’s favourite strategiesamid record-breaking volumes of M&A activity and the large number of 13D filings indicating a strong opportunity set for activist managers. But Amundi has been selective because plain-vanilla merger arbitrage deals still have historically tight spreads, so more complex deals or events entailing corporate restructuring can generate better returns. In 2014 Amundi accurately anticipated that volatility would move higher in the bond markets, improving opportunities for fixed income arbitrage.

Hart thinks that the pickup in volatility may help to accelerate the growth in hedge fund assets. “Volatility coming back plays to hedge fund strengths and we do not see volatility going any lower. Pension funds fear changes in US monetary policy, stability in the Eurozone, and the Chinese stock market,” he adds. In response to these concerns, Hart points out that investment consultants such as Mercer and Cambridge are recommending that their clients use hedge funds for de-risking. In particular “Investors sought equities for growth but might not get that now. They want to lock in gains and think they are in for a bumpy ride – so look to Amundi to reduce volatility,” he is hearing.

Since 2010, hedge fund returns have come down to single digit annual percentages on average, whilst continuing to offer a spread over the risk-free rate that is broadly consistent with historical patterns. Hart’s network of institutional investors seem to be reconciled to this level of return: “Pension funds may be happy with a 4-5% return net of all fees with low correlation to dampen the volatility and manage the downside if markets dislocate and get bumpy again,” he says. “As volatility normalizes we expect alpha to replace beta as the driver of returns,” Hart envisions.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical