After starting his career during the Asian crisis, when Jakarta was overrun by tanks in the late 1990s and confining him to a hotel room, Chenavari founder and Co-CIO, Loïc Féry was unfazed by seeing street riots from his taxi in Athens a few years ago. As he and his Chenavari colleagues conducted due diligences on Greek properties and other investment opportunities, they were happy to dress down in casual clothes. Féry had been waiting for some years for the right moment to initiate a pure play Greek vehicle.

For at least eight years, various mainly US-based hedge funds, real estate and private equity managers have launched equity, credit and private equity strategies containing the words “Greek recovery” in the name. European credit specialist Chenavari is distinguished by launching its strategy with a rather narrower focus.

Greece’s peak to trough GDP contraction of 27%, between 2008 and 2016, was one of the deepest ever seen in a hard currency economy in the postwar period.

Loïc Féry, Founder and Co-CIO, Chenavari

Chenavari, which is one of The Hedge Fund Journal’s ‘Europe 50’ managers, has been closely monitoring Greece for the past decade, but has been very selective about when to make opportunistic excursions into certain niches, and when to remain on the sidelines awaiting factors including deeper value, stabilizing macroeconomic fundamentals or political clarity at EU and local levels. “Back in 2011, senior asset-backed securities with Greek residential mortgages as underlying traded as low as single digits (below 10% of par value of 100) on fears that a Grexit would herald a return to the drachma currency,” says Féry.

These bonds were ultimately redeemed at par, generating the same kind of multi-bagger return similar to more esoteric instruments like Bosnian GDP warrants bought after the Bosnian War in the 1990s.

Between 2011 and 2015, with hindsight there were opportunities in Greece, particularly in sovereign debt, but also pitfalls where some notorious hedge fund managers saw their repeated investments in bank recapitalisations drastically diluted.

Chenavari had a hiatus from making fresh investments but the manager kept its finger on the pulse by staying in contact with CEOs, CFOs, bankers, real estate firms and of course politicians. In 2016, this led Chenavari to pursue several investments and some hybrid financing for the famous shipping industry which was emerging from a period of global distress.

In early 2020, Féry finds the opportunity set compelling enough to warrant rolling out a dedicated vehicle for the first time, since an extended economic depression has created markedly undervalued assets. “Greece’s peak to trough GDP contraction of 27%, between 2008 and 2016, was one of the deepest ever seen in a hard currency economy in the postwar period,” says Féry. “Prime real estate prices dropped by close to 50% and the bank-dominated equity market lost 95% of its value. Now the economy, property and equities are all making some recovery against a backdrop of supportive macroeconomics and politics.”

Economics and politics

Longer term investors are demonstrating some degree of renewed confidence in Greece. Since 2016, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which plunged during the crisis between 2010-2012, has increased every year and in 2017 it surpassed the previous peak of c €3bn seen in 2008. In 2018, the total reached €3.36bn, which is close to two per cent of GDP. FDI is increasing, but from a low base and it falls far short of some other EU countries with comparable GDP per head: Hungary has seen FDI as high as six per cent of GDP recently, while Portugal has often registered numbers of four per cent or more. Greece could catch up as there is plenty of dry powder poised for deployment. Where the previous Syriza Government delayed €10bn of foreign investment in an airport, port renovation, gold mine and property development (according to the Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research) the New Democracy government, along with Enterprise Greece, is embracing FDI more wholeheartedly. Privatisation of ports, marinas, real estate and energy projects should continue to attract more FDI.

FDI is one driver of accelerating economic growth. “The Greek government forecasts growth to pick up to at least 2.8% in 2020 from two per cent in 2019. In its recent upgrade, Fitch expects 2020 GDP growth to increase to 2.5% and the IMF expects GDP growth to also increase to 2.2%. The rating agencies and IMF have been conservative in the past. The new government is pursuing policies to promote higher private investment and if it can sustain the goodwill with its creditors to promote fiscal loosening we believe that the government’s ambitious growth targets are within reach,” says Ahmed El Mahi, senior investment analyst at Chenavari working closely with Féry on the Greek vehicle

Indeed, government finances need no longer hinder growth and might even help it. “After a multi-year phase of austerity measures, and sovereign debt reprofiling, Greece is now one of the few EU countries with a budget surplus. Its cash buffer of c €30bn provides a cushion from having to tap credit markets. But the country is doing so anyway, raising fifteen-year debt at c 1.9%. In February 2020, its ten-year yields dipped below one per cent. Greece has fiscal headroom even within the framework agreed with the EU to raise spending and cut taxes,” adds El Mahi. Income tax, corporation tax, property taxes and VAT have already been cut. Any renegotiation of its 3.5% budget surplus target for 2021 and 2022 could unleash further fiscal stimulus.

Chenavari resumed investing in Greece in 2015, with the help of a local partner, George Elliott from Orasis Capital, when the Syriza Government was in power and enacting severe austerity policies. Now the election of New Democracy and Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, widens the opportunity set. New Democracy was born out of the 1974 revolution that overthrew the military junta, and now has aspirations for an economic rejuvenation and a bold reform program in Greece. These policies not only make FDI more attractive but also have a direct impact on real estate, where lower transfer taxes make it more appealing, and have increased transaction volumes.

€3.36bn

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has increased every year since 2016. In 2018, the total reached €3.36bn, which is close to two per cent of GDP.

Property discount

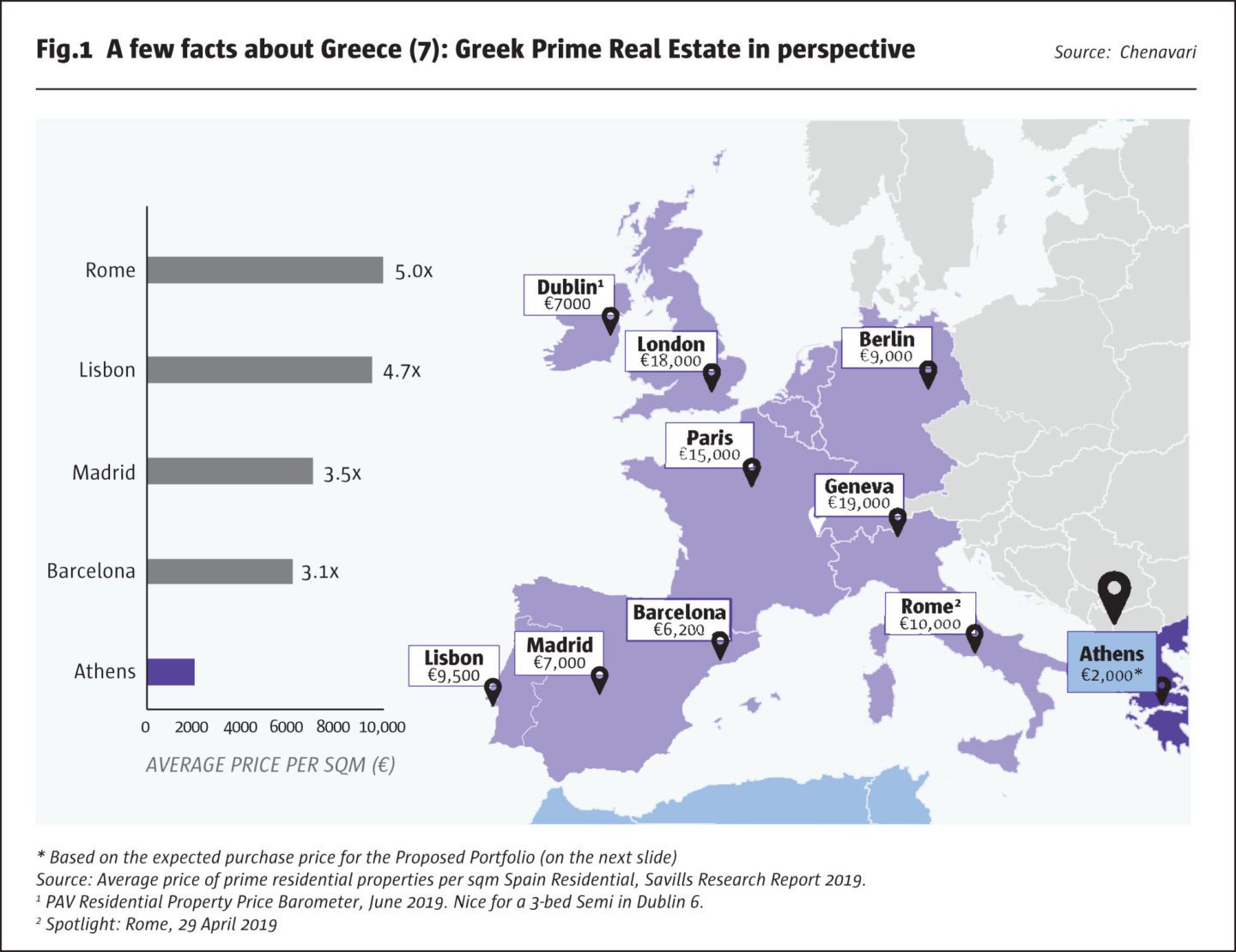

Property could be a key beneficiary of tax reductions, and anyway appears to be deeply undervalued relative to other southern European capitals in Western Europe. Prime real estate values of c €2K per square metre in Athens are at least 70% below the next most inexpensive major city – Madrid at €7K, (and are 85% below London or Geneva), according to data from Savills. Athens property values are closer to those in much lower income countries – Bucharest in Romania or Sofia in Bulgaria – than they are to middle income countries in Western or Eastern Europe. Levels of rents on grade A offices have dropped from a maximum of €30 per square metre, pre-crisis, to €20 today, approximately tracking the decline in GDP.

Yield compression could be one driver of capital growth in property values, where prime office values have already increased eight per cent in the past year according to Savills. The yield pickup in Greece is about 1 –1.5% above the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, which are also in the Eurozone, and about three per cent higher than in Poland. “Yields on prime CBD are being reported at c 7 – 7.5% but we are seeing transactions for specific assets happen at significantly lower yields as the market expects strong rental growth following almost a decade of decline.” says El Mahi. There is a scarcity of Grade A office space in Athens as real estate and private equity investors vie for prize assets. If property yields eventually mimic government debt yields in converging towards European norms, there could be substantial upside based simply on applying a higher multiple to current rental income, which should also grow as the economy recovers.

Chenavari has already agreed to buy several whole buildings in central Athens and envisages end uses that could include hotels, offices, residential flats or student accommodation. Now Féry’s vision is that Athens could become a hub between the near East and Middle East and Eastern and Western Europe, sitting equidistant between London and Abu Dhabi, and halfway between North Africa and Moscow. Greece has long been a popular destination for Russians, including orthodox Christian pilgrims, and Russian tourists do not require a visa during the summer months.

Chenavari has experience of real estate investment in a number of European countries, including the UK, Spain, and Germany. “Longer term, packaging assets into a REIT is one possible exit route, seen in the experience of Spain with Merlin Properties: a sale and leaseback deal of banks’ property exposures where Chenavari acted as an anchor investor” points out Féry.

Yet local banks preoccupied with their non-performing loans – still around 60% of the total – have little appetite for financing lending, while most private foreign banks are also reluctant to lend in Greece. (Development bank the EBRD is active to some degree but it has a limited budget of a few hundred million euros a year spread over a wide variety of projects.)

The other main opportunity in Greece pursued by Chenavari could come from the legacy issues in the banking sector. The Greek banking sector is highly concentrated amongst four banks which makes up of 95% of loans and they are preoccupied with their non-performing loans and have very little appetite to originate new loans. This provides a window of opportunity for challenger banks to capture market share and build a high-quality loan portfolio.

Chenavari has entered into a strategic partnership with AB Bank, the 6th largest bank in Greece, a specialized bank focused on asset-backed loans. Chenavari bought a small stake in the bank back in December 2017 and is now awaiting regulatory approval to acquire a controlling stake in the bank.

Greek’s GDP recovery and growth could trigger high demand for asset-backed secured loans and Chenavari’s strategy is to capture loan demand from under-supplied segments by originating loans with attractive pricing and low LTV (on asset valuations that have severely declined and are in recovery mode).

Credit opportunities

The Greek recovery strategy is also active in a range of traditional and alternative credit assets. “Though the Greek sovereign yields would now require substantial leverage to generate interesting returns, some local authority paper can be worth buying,” says Féry.

In mortgages, the approach is relatively conservative. “We have bought performing mortgage loans acquired at 50-60 cents on the dollar, which continued paying interest throughout the eight-year recession. Part of the edge here comes from partnerships with local servicers.”

In contrast, non-performing loans (whether they are mortgages or corporate loans) are not currently being invested in. “There is still some uncertainty on how long the legal workout process might take. It can take a long time to repossess property, so we would rather just invest directly into real estate at this stage. However, a number of structural reforms have been put in place, so we may revisit it,” says El Mahi.

Investors in the Greek recovery strategy include family offices, insurance companies, other institutions, who are taking a four to six year view on the opportunity.

Kirstie Sumarno, Director of Investor Relations, Chenavari

Unique focus for Greece

Indeed, Chenavari’s Greek exposure remains rather different to its strategies in other parts of Europe. Chenavari’s understanding of Greek assets is informed by having been active elsewhere in the periphery of Europe – in Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Italy, where there are definite parallels in terms of bank deleveraging. For instance, banks’ deferred tax assets form an important part of the assets underlying securitisations. In other countries, including Belgium and the Netherlands, Chenavari will sometimes securitise deals, typically retaining the junior or mezzanine slice and selling on the senior part, but in Greece, El Mahi “expects securitisations to really take off when the sovereign returns to investment grade. The Hercules initiative to securitise the banks’ bad debts could be very positive for Greece.” Similarly, in other countries, Chenavari has been active in various regulatory capital relief trades for banks, but these have not been pursued in Greece in any of Chenavari’s strategies.

Greek corporate debt could be investible by some more liquid Chenavari strategies, such as its Lyxor Chenavari Credit Fund. Although our UCITS vehicle cannot buy Greek bank paper currently due to rating constraints, our team occasionally find attractive relative value trades amongst Greek HY corporate paper such as Wind Hellas, but the Greek recovery dedicated investment vehicle is focused more on opportunities to make two to three times investors’ money,” says Féry.

Chenavari’s vehicles include this liquid alternative credit UCITS strategy, on the Lyxor platform, that was among the top performers in 2017, 2018 and 2019, and has received The Hedge Fund Journal’s ‘UCITS Hedge’ performance awards for best performing European credit long/short strategy. Chenavari also has an active London Stock Exchange listed fund called Chenavari Toro Income Fund and its own CLOs programmes. Expertise spans distressed debt, risk transfer transactions involving regulatory capital and obviously specialty finance private credit where Chenavari is one of the main market participants. As one of the first credit hedge funds that expanded in the private credit space in 2011, the manager also runs c $2.3bn in a growing spectrum of illiquid credit strategies that encompass a wide range of European private credit investments: consumer finance, specialty finance, direct lending, real estate lending, and trade finance.

Investors and co-investors

“Investors in the Greek recovery strategy include family offices, insurance companies, other institutions, who are taking a four to six year view on the opportunity,” says Kirstie Sumarno, Director of Investor Relations, who has featured in The Hedge Fund Journal’s ‘50 Leading Women in Hedge Funds’ report in association with EY. Féry expects capacity of €250 to €300m, and there are also co-investment opportunities for investors. Time is of the essence for potential investors however as end of April will see the end of the first close subscriptions.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical