Investors who focus on the most recent month, quarter or even year of performance for hedge funds should take a step back and consider the perspective of Dixon Boardman, a seasoned pro who has spent nearly three decades investing in alternatives. According to his long experience, “just when the crowd counts an asset class as out is when it often turns around.” The catalyst for such a sea change? Boardman expects markets to become increasingly driven by fundamentals rather than excess liquidity. “We are on the cusp of a resurgence for stock picking. Good hedge fund managers have the potential to outperform by identifying the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in sectors undergoing secular change.”

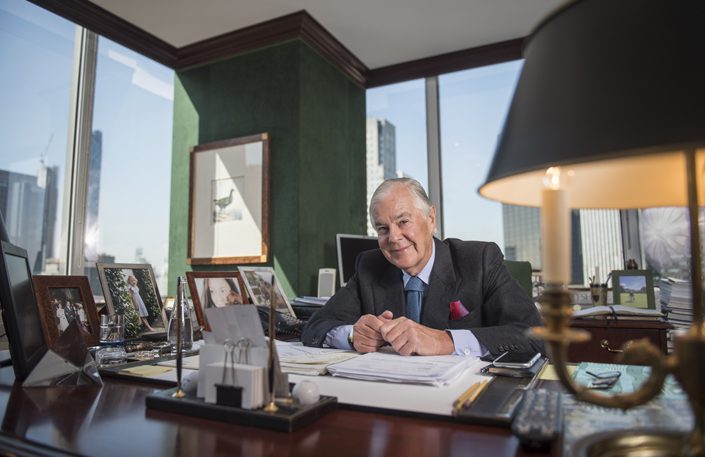

As Optima enters its 30th year of operations, the characteristic bonhomie of Boardman, its founder, is not impaired by the perception that the recent performance of the hedge fund, and fund of funds, strategies, has been lacklustre. Industry performance for 2016 was 5.48%, according to The Hedge Fund Journal Hedge Fund Index, as calculated by Blue Lion Research; various other indices were one or two percent either side of this. When expressed as a spread over risk free rates near zero, these levels of returns do in fact match the targets of certain institutional investors, including some pension funds. European investors in general, and insurance companies in particular, may have relatively undemanding benchmarks. However, the social circles in which Boardman moves include the great and the good of the United States, for whom hedge fund returns have latterly lagged expectations. US pension funds and other US institutional investors tend to have absolute return targets of 7% or 8% that hedge funds, on average, have not met post-crisis. The Preqin All-Strategies Hedge Fund Benchmark made 7.4% in 2016 – but that was its best year since 2013.

The comparatively steady tempo of hedge fund returns has met with a lukewarm reception and, as Boardman observes, “everyone questions fees right across the active investment management industry. There is a total focus on passive management. But whenever a ship tilts all the way to one side, it goes back to the middle or the other side.” He reiterates the ubiquitous disclaimer that “past performance is no guide to future performance” and says that “this is one of the eternal truths of investing”. Colour-coded annual league tables of asset class returns look like a patchwork quilt – the same strategy seldom hangs onto the top spot for more than one or two years in a row – and sometimes last year’s worst sector can be this year’s best.

Indeed “it is often darkest before the dawn,” Boardman points out. If hedge funds are out of favour in some quarters, this may be an opportune moment to invest. Though mean reversion in relative returns is a powerful force, Boardman’s arguments are more compelling than statistical patterns. “Clever people do not become stupid overnight and really clever people run hedge funds,” Boardman contends. He also holds the conviction that “the investment environment is undergoing a radical regime change that will be highly favourable for alternative strategies, including long/short equity and macro.” Optima focuses on these discretionary, fundamental, strategies rather than systematic and quantitative approaches.

A sea change in the market regime?

In macro terms, Boardman thinks that “animal spirits have been reignited for the first time in eight years.” This sentiment is shared by business leaders, including JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon, and is corroborated by synchronised global economic growth. Boardman also sees some prospect of the new US administration pushing through its tax and infrastructure spending proposals, at least in part, by year end. “Even if the US government accomplishes half of its aims, there could be a big impact on growth,” he expects. Boardman further relishes the prospect of monetary policy normalisation – “once artificial manipulation by QE has ended, and the reliance on excess liquidity and central banks has gone, equity markets should be very fertile ground.”

Boardman cites the views of legendary hedge fund investor Stanley Druckenmiller, who seems to have swivelled from being something of a Cassandra at the May 2016 Sohn Conference – when he fretted about equity valuations and corporate accounting – to being a hearty cheerleader, six months later, at a Robin Hood Foundation dinner in November 2016. Druckenmiller envisages that US corporate and individual tax cuts, combined with fiscal stimulus, should promote capital and consumer spending, boosting both nominal and real GDP with inflation and growth. The possibility of ten year Treasury yields reaching 6% by 2018 – levels not seen in a decade – may seem outlandish, but Druckenmiller thinks it is possible (as does esteemed bond manager, and DoubleLine Capital founder, Jeffrey Gundlach). Higher interest rates are feared by many but could, if they increase differentiation between stocks and sectors, be good for hedge funds. In particular, higher rates could prompt “rotation between sectors and reward higher growth and higher quality balance sheets,” Boardman predicts. Greater dispersion between companies, sectors and asset classes increases potential for alpha generation and Druckenmiller therefore expects hedge funds could outperform over the next few years. He is not alone. The latest data from eVestment suggests that the slight net outflows seen in 2016 were an aberration – and not a reversal of the persistent inflows seen every year since 2009. Net inflows into hedge funds have resumed, to the tune of $23.32 billion in the first five months of 2017.

Already, some of Optima’s investee funds have profited from “long positions in banks and infrastructure firms, which could be beneficiaries of higher interest rates, a steeper yield curve and fiscal spending. At the same time hedge funds have profited from the huge trend away from physical retailing and towards internet retailing, by shorting shopping centres and department stores,” points out Boardman.

Optima STAR: Can stock-picking alpha be consistent with low fees?

Optima offers a number of single hedge fund strategies, thus far all in long only, or long/short equity. Optima’s newest strategy, Optima STAR, is available as a daily dealing UCITS and responds to investor concerns over fees by only charging a 1% management fee and no performance fee. The strategy is deceptively simple. Anybody can piggy back on managers’ 13D and 13F filings of stock holdings, and several ETFs do so. “The secret sauce comes in knowing which managers to follow. The Optima STAR strategy comes from a massive amount of work the firm has done on tracking US regulatory filings of managers’ long equity holdings,” says Boardman. These quarterly filings are subject to a time lag of around six weeks so the information might be of little or no use for shorter term traders, or for some activists where a significant part of the move can be seen in an “announcement effect” that occurs almost as soon as the filing is made. However, for some of those managers who tend to hold positions for two years or more, delayed notification of their holdings may have only a marginal impact, according to Optima’s research. Optima does not disclose the names of the managers whose holdings are being heeded. The top five holdings of Optima STAR, as of April 28, 2017, were Amazon, Activision, Facebook, Alphabet and Charter Communications.

Boardman insists that the strategy neither cannibalises, nor dis-intermediates, hedge fund managers’ businesses. After all, this is a long only product and it remains to be seen whether alpha derived from hedge funds’ short books can be accessed at low cost in a similar fashion. Individual managers’ shorts need not normally be disclosed in the US. Though the disclosure threshold in Europe is, ordinarily, a short position of only 0.5% of a company’s equity, many managers who do not want to alert the market to their stance take care to stay under this radar. And regulator ESMA has confirmed, in June 2017, that short positions associated with some offshore vehicles fall outside of the scope of the disclosure rules. Meanwhile, aggregated data, showing overall levels of short interest, is not likely to be useful as the provenance of, and rationale for, the short is not known. Some shorts may be hedging convertibles or other derivatives, rather than expressing outright views, for instance. Overall Boardman finds “those hedge fund managers who have been told about the strategy think it is a good idea.”

Equity valuations

Though Boardman’s case seems to be at least selectively bullish on stocks, partly due to a perceived absence of euphoria increasing potential for stocks to continue climbing, he is cognisant that valuations are full. Not only are PE ratios high, but the profit share of the economy might also be at record levels. Measures such as the cyclically-adjusted Shiller PE ratio make equities look expensive (though this conclusion is disputed by those who have doubts about the comparability of historical accounting data). The possibility that valuations do turn out to have been on the high side, increases the case for a hedge fund approach that can batten down the hatches and even profit from a bear market.

Optima has thrived through at least three equity bear markets: the early 1990s, the TMT bubble bursting in 2001-2002 and the credit crisis of 2008, while Boardman has witnessed many more stock market reversals in his career. Optima’s multi-manager strategies boast some of the industry’s longest track records, which are also unblemished by blow-ups. “We have never attended any funerals of funds and have never invested in a bust fund,” says Boardman. More recently “we have done better than most in the space, but did see challenging performance numbers in early 2016,” he admits. Optima has four long standing multi-manager strategies: US hedged equity, global hedged equity, concentrated hedged equity and discretionary macro. The firm manages around $2.5 billion, of which nearly $1 billion is in a range of customised accounts, including funds of one, comingled funds, ‘40 Act funds, managed accounts and hedge fund platforms. Optima also acts as a consultant, catering for advisory mandates or proffering buy lists.

Fund of funds consolidation

In common with the rest of the multi-manager industry, Optima sees fee pressures and more demand for funds of one and managed accounts, which often involve negotiating lower fees than apply on comingled vehicles. This is one reason why consolidation continues unabated in the fund of funds industry. Optima has naturally been approached about wholesale mergers but Boardman feels “valuations have diminished immensely so it would be foolish to sell now.” (Some years ago, Optima sold a passive 17% stake to BNY Mellon Wealth Management and Mellon Financial Corp, and Optima provides hedge fund recommendations to the latter’s high net worth investor base on an exclusive basis.) In today’s buyer’s market, Boardman has had designs on other firms, but did not do a deal owing to different cultures, which may help to explain why Optima remains resolutely independent. Many corporate combinations are motivated by a desire to cut headcounts. Optima’s organisation is distinguished by its 35-person headcount, which includes a crack “SWAT” team in research and risk management. The bulk of the headcount are in business development, client service, legal and compliance, technology and proprietary systems and operations. “I have always run the firm as a complete risk hypochondriac and have not cut staff unduly,” Boardman is pleased to say. Indeed, the due diligence process requires sign offs by the CIO, CFO, COO, Chief Risk Officer and General Counsel. Particularly noteworthy is that the CFO, Geoffrey Lewis, has been with the firm since its beginnings, a rarity of continuity and experience in the fund of funds business.

Divorces and golf clubs

Ongoing monitoring of funds also entails techniques that might be viewed as unconventional – or even intrusive – by some allocators and managers. Optima’s hawk-like eye on funds goes well beyond analysis of portfolios and regulatory filings. The firm’s unashamedly thorough surveillance reaches into the personal lives of managers, sometimes with the aid of private detectives, but often simply through Boardman and his colleagues’ social lives. For instance, a divorce can be a sufficient reason to redeem if it is messy and stressful but a judgement call always has to be made – so a smooth and amicable divorce might not be any cause for concern. Golf handicaps in contrast can be a contrary indicator. A suspiciously large improvement in a manager’s golfing prowess may mean he or she is frittering away too much time on the green, and this is something that can easily be verified by those with their fingers on the pulse of the social circuit.

Boardman was among the pioneers of the fund of funds industry. In its early days, rolodexes of business cards conferring access to managers were an important source of competitive edge. Managers did not then have websites nor public regulatory filings. Nowadays, it is much less often heard that fund of funds can offer exclusive access to sought after funds. Nonetheless, Optima vehicles do have exposure to luminaries of the industry, such as Philippe Laffont’s Coatue; Chase Coleman’s Tiger Global, Larry Robbins’ Glenview; and Stephen Mandel’s Lone Pine, all of which are currently closed to investors, according to Boardman. He has spent decades rubbing shoulders with the founding fathers of the hedge fund industry. Boardman’s age – he has just turned 70 – is not particularly unusual for a professional or businessperson in the US but his longevity is highly distinguished in the dynamic hedge fund industry (and still more so in the multi-manager space). Boardman’s call for a turning point in the performance of the industry should therefore be lent credence.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical