In today’s world it’s fair to say launching a hedge fund is not as simple as it once was. Gone are the days of one or two people, in a room with a small amount of their own cash and some more from family and so-called friends, trading away with little or no infrastructure.

Prime brokers were willing to accept them as clients, there were no minimum revenue requirements, and the Regulator was at arm’s length at best, providing light touch regulation. Some of those firms have gone on to become the so-called “Titans” of the hedge fund industry. Winton Capital for example launched from a small office in Kensington in 1997 with $1.6m under management and now manages some $28bn.

What does the landscape look like now? Very different is the answer and it doesn’t appear to be getting any easier for the entrepreneur money manager.

Figures this year show a global trend which has seen the lowest levels of hedge fund launches in the opening quarter of a year since 2004. In fact, more hedge funds managed in Europe closed than opened during 2015 – a first. At the same time however allocations to hedge funds still increase year on year.

So where does the money go? Well typically it goes to the “Titan” managers whose assets under management are in the multiple billions and whose owners frequently feature in the Forbes or Sunday Times Rich Lists.

Yet performance for most of the world’s hedge funds hasn’t been great and some of these managers have succumbed to the pressures of it all, returned capital to outside investors and turned themselves into quasi family offices, essentially running their own monies and those of their partners. This trend is likely to continue for the next few years at least or until the regulatory pendulum swings back, but that does not look likely to happen.

Indeed it is the increasing regulatory burden that is holding back the emerging manager. This has been inescapable since the financial crisis. The laws have led to lay-offs, cut off important sources of lending and increased costs for investors without significant concomitant benefit, managers’ claim.

In the European Union, there is wave upon wave of regulatory reform, whether it be the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID), the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR), the Securities Financing Transaction Regulation (SFTR) or the one which has caused the most consternation and debate, the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD).

The AIFMD is considered to be the single most restrictive barrier to entry for an emerging manager. It is seen as costly for investor and manager alike, involving the need for funds to have compliance officers and/or subject matter experts who truly understand the documentation. While several institutional service providers – Maitland included – have developed AIFMD compliant solutions for hedge fund managers, such solutions are generally only cost-efficient for more established managers.

Lack of capital

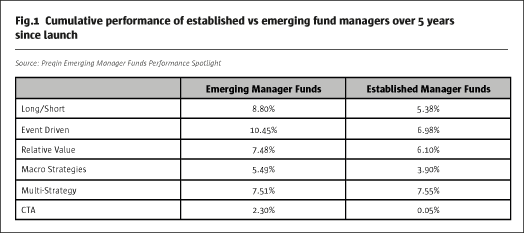

In my opinion, the single most significant reason why there is such a dearth of hedge fund launches is the lack of capital going into emerging managers. The investor wants so much more now than he previously did. Early or seed capital is just not there as it once was and that, coupled with poor overall performance from the sector, just doesn’t make it easy for an allocation to be made to the smaller guys. However, on the positive side there have been fewer liquidations than ever before and the emerging, smaller firms with lower AUM have on average in the first three to five years always performed better than the established, large “Titan” funds, as shown in Fig.1.

New and relatively inexperienced managers find it challenging to raise capital. The lack of a longer track record can make it difficult to attract investors. There are two sides to the operation – running the fund and running the business – and often two very different skill sets are required. New managers these days, along with the regulatory obligations, are required to have a robust and operational infrastructure which obviously increases cost but does reduce the business risk, which of course is a good thing.

If an investor can stomach the volatility of an emerging manager, whilst it tries to raise capital, attract staff, run a business, and run a fund, there is enough evidence that investors who dare to invest with the so-called start-up, are often rewarded with better returns than if they had allocated to a new fund with an established manager. A more volatile level of returns means that start-up funds offer the so-called risk-reward trade off.

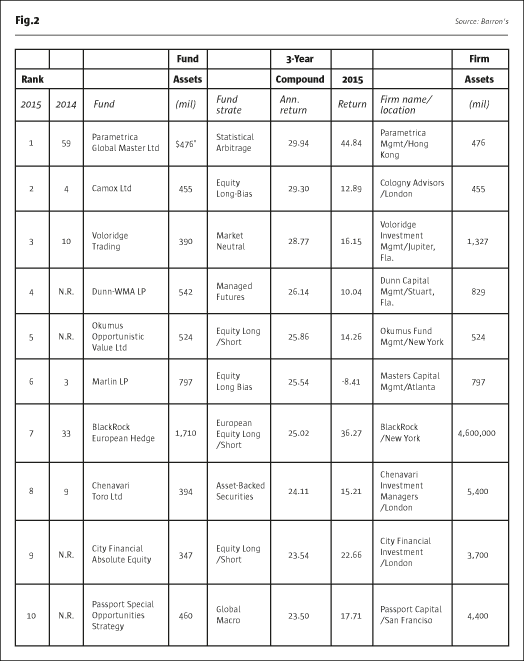

Fig.2 is a chart from Barron’s 2016 List: Best 100 Hedge Funds. Little-known Parametrica Global Master of Hong Kong takes the top spot, while past stalwarts like Pershing Square and Greenlight Capital don’t make this year’s list.

As you can see from the list, in the top 10 alone there are five funds which do not make the infamous billion dollar club!

And finally, as early stage investing goes, look at the returns of some of the people who were early investors into Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook, to name but a few.

So go on – seek the alpha and don’t ignore the start-ups.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 118

Don’t Ignore the Start-Ups

Declining fund launches and the case for the smaller manager

LUKE SPENCER-WILSON, SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT – ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS, MAITLAND, LONDON

Originally published in the November | December 2016 issue