Volatility is back! Depressed for years after the financial crisis of 2008 by zero-rate and quantitative easing (QE) policies of major central banks, markets are again responding to a variety of different and hard-to-forecast developments. In this article, we summarise five major debates feeding more volatility into markets.

- US rates: the Federal Reserve rate-rise decision appears to be mostly about timing, but a temporary bout of weaker data in Q1/2015 and a data-dependent Fed are keeping the markets guessing.

- US Treasury bond yields: QE in Europe, Japan’s depressed yields, and dried up liquidity increasing the risks of abrupt price moves. US Treasuries are now a “high-yield” bond, confusing the outlook considerably.

- US equities: corporate earnings struggle to grow when top-line revenue is constrained by low inflation and a lack of pricing power. Even with comfortable multiples and merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, earnings disappointments can add volatility.

- Crude Oil: oil companies would rather lose a little money for a few years than go bankrupt, so cash flow needs are trumping break-even costs, even at sharply lower oil prices.

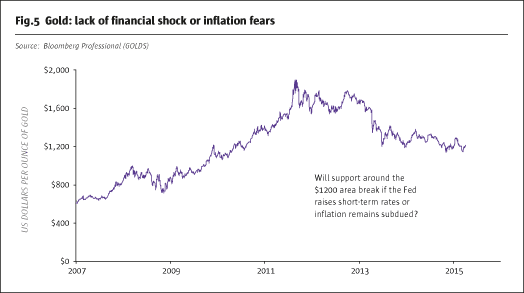

- Gold: there is a lack of financial fear or worry over rising inflation, so if the Fed does raise rates, gold could be in the cross-hairs.

1. US rates

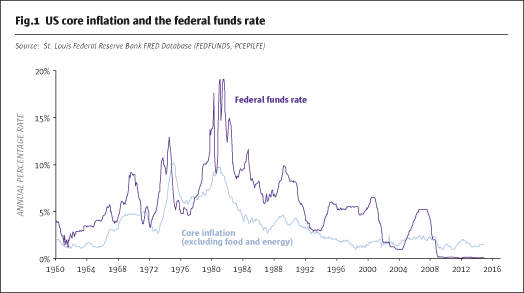

There is solid growth in US employment, despite a little less strength in March 2015, and a sense that deflationary pressures, driven in part by lower oil prices, are abating. These fundamental forces have placed the Federal Reserve’s debate on interest rates front and centre. Will the Fed move to abandon the zero-rate policy and raise its target range for the federal funds rate in 2015 (see Fig.1)? Our sense is that there seems to be a growing consensus among the hawks and doves within the Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) that eliminating negative real rates – that is, keeping the federal funds rate below the core rate of inflation – is no longer appropriate after five years of solid, if not exciting, economic growth. The timing of any rate move remains in doubt.

Q1/2015 real GDP was on the weak side, and international factors, including a strong dollar and a decelerating China, argue for a delay. The ebb and flow of the Fed’s rate debate is going to keep the short end of the US maturity curve dancing, because the Fed has made it abundantly clear that its decisions are data-dependent, and the data is simply getting noisier.

2. US Treasury yields

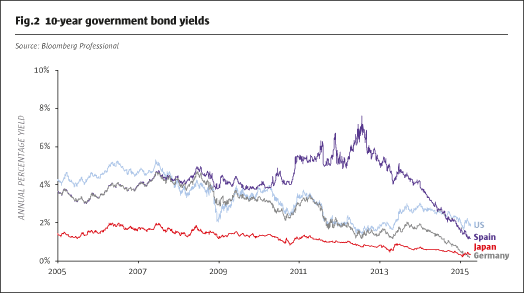

Within the debate about the timing of a possible rate-rise decision by the Fed, one scenario would have US Treasury yields moving higher in anticipation – but this is not so clear. There are powerful global constraints on higher US Treasury yields. The massive asset purchases by the Bank of Japan and more quantitative easing from the European Central Bank (ECB) and its Eurozone national central banks set for 2015 have driven 10-year Japanese and German bond yields lower, while drying up liquidity in these markets. Even Spanish and Italian 10-year bonds now yield less than US Treasuries (see Fig.2).

As conservative global investors search for yield, “high-yield” US Treasuries will remain a favourite. But shocks in Europe, where ECB QE has removed liquidity, may bring abrupt price shifts that also hit US Treasuries. So, the Fed debate may be driving the short end of the maturity curve, but BoJ and ECB QE are making it more likely that the yield curve flattens rather than experience a parallel upward shift. On the US domestic front, the Fed ended its QE in October 2014, and growth in the supply of new Treasury securities is shrinking as the US federal budget deficit fades away. Taken together, it is a prescription for substantial volatility within a wide range.

3. US equities

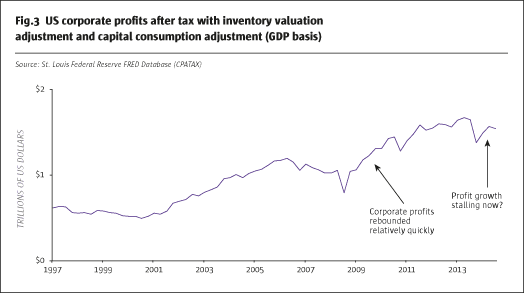

Growth in corporate earnings is coming into the spotlight in the US. The lack of inflation in the US has constrained top-line revenue growth, making earnings growth increasingly dependent on narrowing expense margins. Based on profits data contained in lagging real GDP reports, the earnings deceleration is well underway (see Fig.3).

While price/earnings multiples remain in a comfort zone, and potential M&A activity can spur market rallies, the longer-term challenge to ever-rising stock prices is profit growth – or the lack thereof. This source of volatility is being magnified by the problems in the energy sector, where oil prices have tumbled under the weight of abundant supplies, as well as a weak Q1/2015 US real GDP, given: (a) savings on gasoline prices have not made their way into discretionary spending yet, and (b) the West Coast dock disruptions were more economically damaging than discerned by East Coast analysts. As earnings reporting season arrives, so may more equity volatility.

4. Crude oil

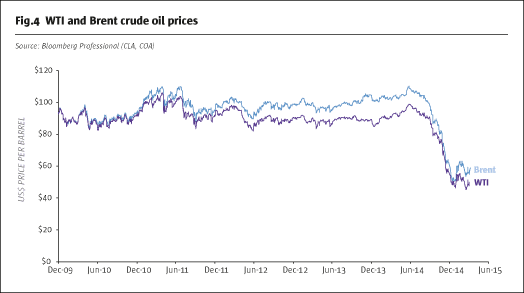

In the oil sector, markets appear to be settling into a very wide trading range, roughly $45-$70 per barrel in terms of WTI crude oil (see Fig.4). While some rigs have been shut down, oil companies need to keep the oil flowing to keep the cash coming in so they can pay debts and bills. It is generally perceived by CEOs that taking some losses for a few years is much better than immediate bankruptcy, so cash flow trumps the economics of perceived break-even rates for production costs.

For oil prices to break out to the upside, they would require: (a) severe disruption to the flow of oil from the Middle East, or (b) sustained and robust growth paths in emerging market economies, including China. The former is not likely, and the latter is not happening. China continues to see its growth rate decelerate, and indications are that it may be happening a little faster than the slow march downward as suggested by official government growth targets.

5. Gold

Gold is generally bought as a portfolio hedge when fears of financial instability rise or as a store of value in times of inflation. Neither of these factors is in play now (see Fig.5).

Indeed, if the Fed does move to push short-term rates up toward the rate of core inflation in the US, then there may develop increased downside risk for the price of gold. On the global front, the two big bullion buyers, India and China, are headed in opposite directions. China is decelerating while India is experiencing robust growth under its new government. Volatility could emerge from an unusual source: the Chinese currency. The Chinese RMB has been managed in a tight range with the US dollar, meaning that the RMB has been quite strong against most of the world’s currencies, along with the US dollar. The strength of the RMB has probably caused an even greater deceleration of Chinese exports; so if the RMB trading range were to be widened, weakness is possible. Any RMB weakness could spur Chinese demand for gold as a hedge.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 104

Five Sources of Upcoming Volatility

The return of unpredictable market moves

BLU PUTNAM, CHIEF ECONOMIST AND MANAGING DIRECTOR, CME GROUP

Originally published in the May 2015 issue