In The End It’s The Fundamentals That Count

Why the outlook for currencies has rarely been better

Interview with ADRIAN OWENS, INVESTMENT DIRECTOR, GAM

Originally published in the October 2014 issue

“Currency investing is going to see a comeback.” That’s the view of GAM’s Adrian Owens, whose strategy – GAM Discretionary FX – has returned 29.4% year-to-date (gross of fees in US dollars to 30 September). One could be forgiven for thinking that currency as an asset class has fallen out of favour with clients as their portfolio managers struggled to generate returns, as evidenced by the broadly flat performance of the HFRX Macro Currency index over the period from July 2007 to September 2014. Owens, however, is not perturbed: “The current opportunity set has rarely been better,” he claims.

Currency is well known for being a notoriously difficult asset class in which to consistently generate return. Two reasons stand out. First, the asset class is often cited as exhibiting characteristics close to ‘perfect competition’, with a very large number of buyers and sellers, low barriers to entry and transparency of information. In such a market, excess profits are hard to generate. But currency is also different for another reason. When investors buy equities or bonds, they are lending money to a corporate or government that pays for that money in the form of a yield (beta). Currency is different: an investor is not lending money in the same way. Therefore, there is effectively no automatic beta (yield). A currency manager generally seeks to generate returns by identifying currencies that will rise or fall (alpha). This is a much harder task.

The financial crisis and the advent of QE have also changed the landscape. QE has been a godsend for long-only equity and bond investors, with both asset classes rallying strongly on the back of central bank liquidity. Although the ECB and the Bank of Japan are still pumping liquidity into the system, the Fed is close to finishing its QE programme. Of the major asset classes available, investors have the choice of investing in developed market bonds with record-low yields, credit with close to record-low yields or equities that have rallied strongly since 2009 and have benefited hugely from QE. In Owens’ view, this is not a particularly attractive opportunity set when compared to the opportunities on offer in the currency markets.

While he recognizes that currency markets have a “degree of efficiency”, Owens disputes the general assumption that they are perfectly efficient. This is because currency markets include a lot of price/value-insensitive participants. Corporates will often need to undertake transactions irrespective of price, systematic investors may buy currencies purely for reasons of momentum or carry, and official buying used to manage individual domestic agendas may give rise to temporary distortions. Even fundamentaleconomic changes can sometimes take time to show up in currency moves. Owens gives an example: “Over the course of this year, ECB President Draghi had become increasingly vocal over the Council’s desire to weaken the euro. Of course, his language was often guarded, but it became less so as the year unfolded. However, it took the market until July before it really began to listen.”

Don’t ignore sentiment

Identifying these opportunities and benefiting from them is Owens’ daily business. “Traveling to various countries to meet central bankers and government officials is unlikely to give much more than is already in the public domain,” he says. That is why he prefers to spend his time at his desk, working on portfolio strategy, making sense of the data that appears on his screens and discussing ideas with his team members.

But it’s not all about figures. Other factors, such as sentiment and psychology, play a role too. He learned this principle many years ago when he took on his first job as an economist in the City at Yamaichi Securities, a major Japanese broker firm. When he joined the team from his previous job at the UK Treasury, he was surprised how many traders would often take positions based on little more than instinct and some basic chart formations, with little or no consideration of the underlying fundamentals. Nevertheless, Owens recalls his time at Yamaichi fondly, as the traders there taught him a hugely valuable lesson: “You have to know when to put the numbers to one side. At times there are other factors at work driving markets.” When this happens, it is often time to cut risk.

Owens admits that the frequent public mutterings of politicians and central bankers sometimes leave him frustrated. But he also sees the opportunities that are created by short-term market dislocations. He acknowledges that while it is important to listen to policymakers, they rarely offer additional information to investors and they get it wrong too. One core belief has always remained undisputed for him: “The fundamentals will win out eventually.”

Long-term approach pays off – over time

Owens’ investment process goes some way in ensuring that he maximizes his chances of investing profitably. His focus on fundamentals is reflected in the longer-term approach that characterizes most of his positions. He begins by analysing the key global market drivers, then pinpoints the economy’s current position in the cycle and develops his market outlook. Focusing on the liquid G20 countries, the next step is to analyse those currency markets against his findings, while also looking opportunistically at investment potential in emerging markets. Owens will then build valuation metrics and determine fair values for his currency pair trading ideas. This includes setting stop losses should trades go the wrong way. Finally, he will prioritize trades depending on his level of conviction and select the best assets and instruments to put his ideas into practice. The timing and size of each position depends on a host of factors, including conviction levels, the correlation of trades and technical analysis.

The longer-term approach has also proven to be the right one for him in the current environment. “Trying to trade short-term moves is difficult,” Owens admits. “You need to be able to rely on your analysis and not get distracted by other people’s views or comments. The aim is to identify sentiment shifts and indications for growth early on. If you feel that the underlying story is continuing to unfold in the right way, then use the volatility to add to positions.” That worked for Owens recently for a short sterling versus the US dollar trade. He had initiated the trade early in 2014 at around mid-1.60 levels. In the first two to three months the trade suffered some losses as Owens was somewhat early to the trade and sterling continued to appreciate on the back of strong UK economic data. “We actually added to the position at levels above 1.70 as we continued to believe that the fundamental backdrop should see sterling weaken. The currency had already materially strengthened and we expected the anaemic state of the eurozone – the UK’s largest trading partner – to dampen economic activity, and the appreciation in sterling to start to impact the inflation and activity data. The view finally played out in July and August, as it became increasingly clear that the dollar had superior fundamentals to sterling. Concerns over the Scottish referendum were a bonus for the trade, and the already weakening pound was hit further on the back of polls showing growing support for independence. Owens used these concerns as an opportunity to take partial profits on his position.

When it comes to managing money, being an economist by trade has both advantages and drawbacks, Owens explains: “The danger of being an economist is that one can often be early to initiate a trade as shifting fundamentals often take time to show up in prices. This has happened to me numerous times, and tends to result in some intermittent flat or even negative performance until such time when the fundamentals finally do win out and the trade comes around. This typically results in a sizeable boost to performance as we try to size our high-conviction trades accordingly.”

Navigating the challenges of 2011

The year 2011, which culminated in the euro crisis and the distortions it brought to currency markets, is one that many fund managers would probably rather forget. Owens shares these feelings. His portfolio suffered its worst-ever drawdown, as “everything that could go wrong did go wrong”. With fears over a eurozone break-up increasing, the Swiss franc continued to appreciate, reaching never-seen-before highs. Owens went short the franc versus the Canadian dollar, “as I felt that it made much more sense for people to move their assets into a true safe haven, as Switzerland was economically too closely tied to the eurozone’s fortunes for it to escape unscathed.” However, the franc continued to move higher versus most currencies, including the Canadian dollar. After a few very painful months, he stopped out of the position as it was simply not clear how far this irrational behaviour could push the franc.

When outright panic engulfed markets, Owens finally felt that the peak was close and prepared to re-engage his franc short. But around that time the Swiss central bank intervened to establish a floor at 1.20 against the euro. Owens looks back at those days with frustration: “We had the right idea, but it disappeared before our very eyes. The most annoying aspect is that even when we have stopped out of a trade, if the fundamentals are still moving the right way we will monitor it, and when the price action improves we will often re-enter. Looking back over past themes that have cost the fund, we have often been able to recoup 50–60% of our losses by re-entering once the trade turns. However, with this particular trade, that was not possible once the floor had been established.”

During the summer of 2011, Owens was also worried about the euro and had concerns that the euro would have a negative knock-on effect for ‘risky’ currencies. Consequently, he ran short positions in the euro as well as the Australian and New Zealand dollars. However, despite concerns over the euro, it initially failed to depreciate as money was repatriated into the region. And despite a pick-up in volatility the Australasian pair remained remarkably robust, as it later became evident that central banks appeared to be active buyers over this period.

“It certainly ruined that year for us performance-wise,” Owens concedes, “but fortunately, this was an extremely rare occasion and we managed to more than recoup the losses in the subsequent year as some of these positions worked and other ideas played out.” Since the trough in September 2011, the fund has gained 57% (to 30 September).

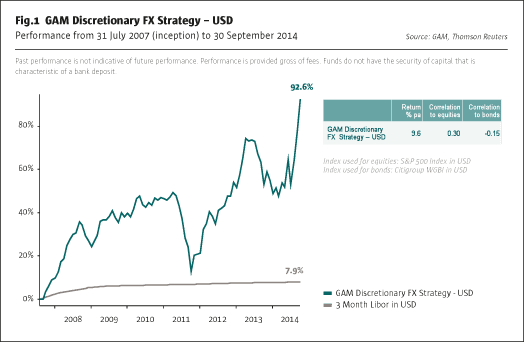

Given his investment approach, Owens is keen to point out to potential investors that “it is more important than ever to be patient. Those who can’t tolerate a few consecutive months of weakness will probably not be content with my approach to currency investing.” His track record, however, is likely to convince people to stick with Owens over the long term. He has been managing currencies since 1997 and since 2004 as part of a combined sovereign bond and currency hedge fund – his successful flagship US $3.2 billion (as at 30 June 2014) Global Rates strategy. His dedicated currency-only strategy incepted in July 2007 and has returned 9.6% per annum (gross of fees). The corresponding UCITS vehicle launched in 2009.

Profit from the strong US dollar trend

A trade that is currently working well for Owens – and should continue to work in his view – is being positive on the US dollar versus the euro. It has been a strong performance driver of the year-to-date return. As the rationale behind it is well known and it is a fairly consensus view, Owens has added numerous aspects and angles to the theme in order to not be overexposed to a crowded trade. He explains: “A stronger US economy has an impact on other countries that have close trade links with America – for example Mexico and Canada. On the other hand, the pressure on the euro is felt in the periphery, including Poland and Sweden. Our view is that we are currently seeing one of the clearest cases of economic and policy divergence between the two blocs that we have witnessed in many years. I think the sheer amount of pressure from central bankers and politicians on the euro to devalue to combat unemployment had initially been underestimated by many. The European electorate is keenly aware of the continent’s problems. This was reflected in the latest round of European elections, which saw extremist parties rise in popularity. We believe that the divergence in Europe’s economic backdrop versus the US is far from priced in, and hence we expect this theme to potentially run for another 18 months.”

Owens is not worried that the US will start to oppose euro strength. “Of course, the pace of decline is always important, and few policymakers would want the adjustment to a weaker euro to be too rapid.” But in Owens’ mind the ultimate direction should be welcomed by policymakers in Europe and the US. The US economy is growing strongly and unemployment is rapidly approaching the Fed’s estimate of full employment. Importantly, the US is also a relatively closed economy so a strengthening currency has limited effects on growth and inflation. “A rebalancing towards a stronger dollar against a number of currencies has been long overdue,” he adds.

Opportunities ahead

With the Fed’s tapering and the gradual removal of QE, Owens feels that finally economic fundamentals are coming back to the fore in driving exchange rates. He welcomes this development, which should play to his strength as an economist. At the same time, competing risk assets, such as equities and credit, which have been huge beneficiaries of QE, are likely to struggle, believes Owens. “The hunt for yield has pushed various areas of global stock markets to very high levels, while high-yield bonds have not been living up to their name for some time. QE has also meant that asset classes that have previously moved in opposite directions, namely equities and government bonds, have moved in tandem.” With these factors in mind and with the divergence between the euro area and the US so stark, the comeback for currency investing could be just around the corner.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical