Japan has, due to Abenomics and the aggressive monetary policy of the Bank of Japan (BoJ), become of increased interest again to many global allocators, and the announced shift in asset allocation by the Government Investment Pension Fund (GPIF) in November 2013 was seen as a further potential boost to equity markets. This has given rise to record inflows into Japanese equities, totalling over $150 billion in 2013, of which approximately $44 billion came from mutual funds. Since the announcement of Abenomics in December 2012, through 31 December 2014 the markets have rallied about 80%. Over the same timeframe the JPY has lost over 40% of its value versus the USD.

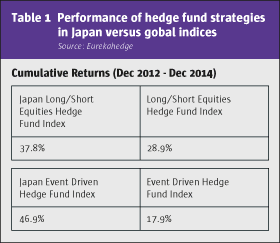

In 2013 Japan was the best single country-focused hedge fund strategy, and Japan event driven was among the top-performing hedge fund strategies globally since the announcement of Abenomics in 2012 until the end of 2014 (see Table 1).

While these trends have been discussed widely, and though the stimulus is clearly helpful and a good manager should be able to extract beta when it is offered, what perhaps is less well understood is that Japan exhibits a number of unique features which make it one of the few global markets to allow experienced hedge fund managers to extract ongoing alpha and uncorrelated returns in addition to or regardless of macro/stimulus-related events.

The focus for hedge fund investors should therefore be on the idiosyncrasies of the Japanese market rather than taking a directional or macro view. Allocators should look at investments in Japanese hedge funds in relation to how the risk-adjusted returns they offer fit into the return profile and expectations of their overall portfolios and focus on the alpha they generate. The fact that they happen to extract these returns from the Japanese market should become a secondary consideration. The idiosyncrasies of the Japanese market are what provide the fertile ground from which experienced managers can extract alpha and returns not correlated to macro trends. The corollary to this is that it is very important for allocators to be able to distinguish between those managers who are able to take advantage of these unique characteristics of the Japanese markets, in some cases with remarkably low net exposures, and “beta hunters”.

Generally speaking, we also see a clear difference between local managers and global funds allocating to Japan. Global funds typically allocate to Japan on a macro basis, not fully taking into account valuations, and often lack the ability to exploit the unique structural features of the market, thereby further supporting market mispricing. For instance, last October’s announcements by the BoJ on further monetary easing and the changes in the asset allocation policy of the GPIF triggered the largest net asset purchases by global hedge funds in Japan since March 2013.

Though the unique features of the Japanese

market are numerous, one of the most compelling may be the depth of the market. Japan is the third largest stock market in the world, with a market capitalisation of approximately $4.4 trillion and approximately 3400 listed companies. A Financial Times article in 2013 estimated no more than 30% of these have some (oftentimes limited) analyst coverage, leaving 70% of listed companies with no coverage at all. Nomura, for example, historically only covered a little over 500 companies. Additionally, many of these are small and mid-cap companies; 46% of listed stocks fall outside the TSE First Section. For a hedge fund manager that is able to conduct independent fundamental research, this presents extensive opportunities for generating uncorrelated returns, as prices can often be driven by retail investors with little fundamental knowledge of these companies. This often results in significant gaps between real values and the market price. These types of mispricing are much harder to find in more developed markets such as the US where, according to Cambridge Associates, over 80% of investible companies have analyst coverage. These opportunities are by no means just limited to small and mid-cap stocks, and we have seen Japanese managers significantly outperforming large cap indexes on a risk-adjusted basis as well.

The last crisis in Japan has left the hedge fund industry with a significantly smaller number of participants and less competition, pitting in effect a small number of professional, and often very seasoned, money managers against mainly retail investors. In the US the ratio of hedge fund assets versus market capitalisation is about 5.94%, whereas in Japan this is only about 0.33%. It is easy to see how this dynamic can create a very attractive environment for hedge fund managers. Though other markets have similar ratios (for example, approximately 0.4% for China and approximately 0.09% for India), many of these do not have the liquidity, regulatory framework, the ability to short or the number of stocks to choose from offered by the Japanese market.

The protracted Japanese bear market has also acted as a proving ground for local managers,and has taught them how to effectively hedge their downside, as otherwise they wouldn’t have survived. We feel that this “education” is another quite unique aspect of the Japanese fund management industry. To illustrate this further, the Eurekahedge Japan Hedge Fund Index has been able to generate annualised returns of approximately 6.5% since January 2000, while the Nikkei 225 and TOPIX Indexes have had annualised returns of about -0.5% and -1.3% respectively for the same period.

Cultural differences, including of course the not insignificant language barrier, are also opening up new opportunities. The introduction of the Stewardship Code is one such example, whereby soft activism will likely start to play a more important role in opening up additional opportunities, but with a need to understand Japanese sensitivities and adopt a different approach to that which the typical US activist manager might take. Changes to corporate practices should have a long-term positive impact on businesses, earnings and therefore valuations. The code, which promotes best practice for shareholders, will add return on equity pressure. According to the Financial Times, it forces asset managers to engage with management teams on matters related to business strategy and corporate governance to avoid votes being cast like a “mechanical checklist”. This should further benefit local managers. Additionally, the new JPX 400 index, which pension allocators are now using, will also encourage companies to stand out by improving their return on equity for stockholders.

All of these elements make Japan a fairly unique market for hedge funds. This can be seen by the quality of existing managers, who over the last 15 years have delivered compelling risk-adjusted returns despite at times very difficult market conditions. They are among the few funds that have been consistently generating alpha rather than beta returns. In an environment where alpha has become ever more challenging to generate, and where most managers have been struggling to do so, Japan seems to represent a compelling investment case. For these reasons we believe that Japanese hedge funds should form part of most allocators’ portfolios and warrant serious consideration irrespective of one’s macro view of Japan.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 101

Japan Offers Unique Alpha Opportunities

Why allocator interest in the market is increasing

PATRICK GHALI, MANAGING PARTNER AND PABLO URRETA, PARTNER, HEAD OF RESEARCH, SUSSEX PARTNERS

Originally published in the January 2015 issue