In collaboration with Nobel Prize-winning economist, Dr Harry Markowitz, BNY Mellon’s Investment Services and Investment Management groups have combined resources with HedgeMark International, LLC to provide an inside look into the institutional investment risk management field. The full paper can be viewed here.

In our previous white paper, which also included valuable input by Dr Markowitz, we found that pension funds and non-profits were just starting to take a more serious look at risk management. Now, some eight years later and post the 2008 financial crisis, our 2013 survey shows that risk management is more critical than ever. Among our major findings:

The 2008 financial crisis – a new awakening of risk awareness: the 2008 financial crisis caught many institutional investors off guard. The risk management procedures then in place were widely perceived to be insufficient for a crisis of such magnitude. The drive for more effective, holistic risk management was soon on.

Increased use of alternatives: survey respondents have expanded their use of alternative investments to improve diversification and potentially help with downside risk. Institutional investors plan to increase their allocations to alternatives over the next five years.

No more chasing alpha: it’s down with alpha and up with targeted returns. Institutional investors are placing greater emphasis on achieving absolute return targets as opposed to outperforming a market benchmark. Risk budgets, matching liabilities and avoiding downside risk all play an important role in this shift.

Analytical tools on the front lines of risk management: analytical tools based upon risk/return analysis and performance attribution continue to be the most commonly used to model, analyse and monitor investments. Total plan/enterprise risk reporting tools are on the rise to encompass traditional and alternative investments, as well as liabilities.

Avoidance of unintended bets: a desire to avoid unintended leverage and to better understand underlying investments has grown markedly since the 2008 financial crisis and appears to be driving institutional investors toward solutions offering greater investment transparency.

Foreword by Harry Markowitz, Ph.D

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away – or at least it seems that way as compared to the risk control procedures now practiced by institutional investors, as reported herein based on BNY Mellon’s risk practices surveys of 2005 and 2013. Actually, it was sometime in 1950 while reading John Burr Williams's Theory of Investment Value (Williams, 1938, 1989, 1997) in the library of the University of Chicago’s GSBA (now called the Booth School in honour of a benefactor who made his fortune in what might be called the MPT industry) that it struck me that the financial theory of the day did not adequately account for portfolio risk. I am of course delighted to see from the two surveys that MPT continues to be used as a major tool in portfolio management, and that the ideas that came to me almost exactly in the middle of the last century are still referred to as Modern Portfolio Theory. Multiplying the percentages reported in the surveys times the size of the institutional investment management industry – let’s say it is up to $30 trillion – suggests that tens of trillions of institutional AUM (assets under management) are managed with the aid of MPT.

I will not try to summarise the results of the two surveys. The paper does an excellent job of that. Rather I will share with you some thoughts about the lessons learned since our 2005 white paper, and express some concerns about where we are heading.

Was 2008 really that shocking?

The survey makes it clear that the industry was shocked by 2008. I, personally, am shocked that the industry found 2008 so shocking. Based on historical returns since 1926, large cap stocks fell about two and a half standard deviations below their long-term average return. If annual returns were normally distributed (mind you, I did not say they are, just if they were normally distributed) then a downward move of two standard deviations or more would happen roughly 2.5% of the time. That is, one year in 40. Since I have been in this business for over 60 years, I was overdue for a one-year-in-40 event.

The following specific morals can be drawn from the fact that once-in-40-years events happen from time to time: the survey reports an increased interest in a portfolio’s Value at Risk (VaR). I have no objection to using VaR as one way to characterise a mean-variance efficient portfolio’s risk exposure; but I hope top management understands that VaR (at the 5% level) is not the most a portfolio can lose, but the least it will lose 5% of the time. Since 5% is one period in 20, losses somewhat in excess of the 5% VaR point (say, between the 1% and 5% probability levels) should be considered routine events in portfolio management.

In late 2007 through early 2009 in particular, pension funds that stayed with an old-fashioned 60/40, or 70/30 or 50/50, or such, mix of stocks and bonds(including an efficient mixture of asset classes such as large cap, small cap, developed markets, emerging markets, and long-term, short-term and high-yield bonds, for example) rebalanced near the market’s nadir while those who were too clever by half suffered tragically.

The danger of using alternatives for diversification

The 2013 survey reports an increased use of alternative investments with diversification rather than enhanced expected return as the principal motivation. The goal of diversifying a portfolio by adding exotic asset classes has sometimes proved quite disappointing, and predictably so. The formula for the volatility of a portfolio is rather complicated. Depending on lots of different correlations between the returns of a proposed security or asset class with those of others in a portfolio, the adding of a more volatile security or asset class may or may not reduce the portfolio’s volatility. Estimating volatility of illiquid investments can complicate risk calculations, and some alternative investments intend to reduce beta rather than increase beta.

However, if an investor is exposed to exotic high-beta alternative investments, the result may be that the exotic security or asset class goes down in flames at the same time traditional asset classes are struggling. The institution then says that portfolio theory with its touted diversification benefits (as represented by some sell-side quant) has failed.

The solution here is simple. The institution should have a trusted quant team make forward-looking estimates of means, variances and covariances involving this security or asset class, perhaps with the help of the factor model of their choice. These estimates, along with such estimates for traditional securities or asset classes, should be presented to the MPT optimiser along with the institution’s legal, institutional, turnover, liquidity, multiple objectives, client preferences and other constraints. The efficient frontier generated by the optimiser from these inputs may or may not have portfolios that use the proposed security or asset class. So be it.

The trusted quant team in the previous paragraph is presumably either that of the institution or a consultant, depending on who regularly produces the institution’s efficient frontier. As the survey notes, sometimes such matters are done in-house and sometimes they are farmed out. If the trusted team errs too badly too often, the institution should hire or develop a different trusted team.

Using the appropriate measure of risk

The survey notes that many pension funds, especially private as compared to public pension funds, have switched from performance-versus-a-benchmark to asset-returns-versus-liabilities as their objective. The moral here is that an MPT optimiser is quite flexible with respect to such matters. The institution needs to identify its objectives and share them with the optimiser. For example, in advising an individual investor a CFA or CFP should usually use the total volatility of the client’s portfolio as its risk measure; whereas a money manager who is paid to outperform some index should use tracking error as its risk measure; and a pension fund should naturally use the volatility of asset values minus liability values as its measure of risk.

As noted in a comment in the survey, if the volatility of assets-minus-liabilities is the correct risk measure for a particular portfolio, such as a firm’s pension fund, that doesn’t mean that its portfolio should be immunised. That would be the minimum-risk solution for such a portfolio. But the MPT view is neither to minimise risk nor always maximise return, but to consider the possible trade-off between them.

All crises are different

The crisis of 2008 was different. So was the crisis that started inMarch of 2000 with the bursting of the tech bubble. So will be the next crisis, as were all the colourful crises reported in Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (Mackay, 1841, 1852, 1980). The moral is that one will never be able to put the portfolio selection process on automatic. The trusted quant team needs to constantly evaluate the current situation. It should also make sure that higher management understands what assumptions are being made, how and by whom any exotic asset classes being used have been evaluated, and what are the vulnerabilities of the general approach being taken.

Furthermore, the push to integrate risk control at the enterprise level, rather than at the individual portfolio level, should be continued. More generally, the many charts, tables, revealed trends that follow and the comments on them concerning both investment risks and operational risks in the surveys reported below should be given the most serious consideration.

INVESTMENT RISK

Market risk

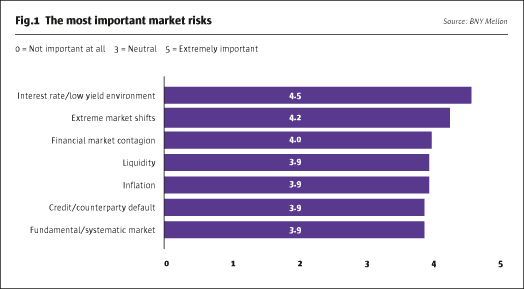

Survey responses suggested the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession not only increased institutional investors’ desire to implement risk management practices, but directly influenced their priorities and the kinds of risk management practices implemented. For example, the low-yield environment, extreme market shifts, financial market contagion and liquidity responses were rated as the most important market risks facing institutional investors in the 2013 Risk Survey. In fact, 100% of pension funds rated “the interest rate and current yield environment” to be either an important or extremely important market risk.

The market risk categories whose importance increased most since the 2005 survey were “derivatives volatility, extreme market shifts, liquidity, financial market contagion and credit/counterparty default risks,” all emblematic of the 2008 financial crisis (see Fig.1).

Investment risk measures

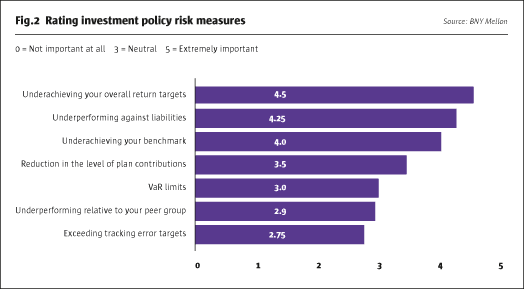

In a significant shift since our 2005 survey, respondents to the 2013 survey rated “under-achieving overall return targets” and “underperforming versus liabilities” as their two most important risk policy measures (see Fig.2).

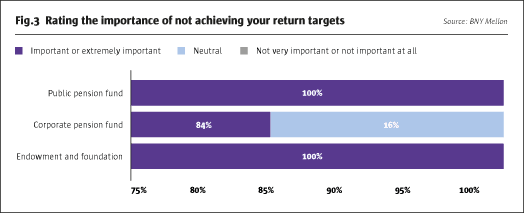

Between the 2005 and 2013 risk surveys, these two measures increased more than any other response within this section. If one considers liabilities as a form of performance target, the general shift in the focus of risk management from relative-to-benchmark to relative-to-target outcome becomes even more apparent. The “reduction in the level of plan contributions, VAR, and exceeding tracking error targets” all support the importance of achieving objectives relative to targets. Drilling into the detail, we can see that 100% of public pension funds and 100% of endowments/foundations said “underachieving overall return targets” was “important or extremely important”; 84% of corporate pension funds indicated the same (see Fig.3). None of the endowments/foundations, public pensions or corporate pensions indicated underachieving return targets was unimportant. In some cases, achieving return targets also implies avoiding downside risk.

Performance versus liabilities

Looking more closely at performance versus liabilities responses, we can see that 94% and 82% of corporate pensions and public pensions also indicated underperforming against liabilities was either extremely important or important (see Fig.4). The lower response from public plans relative to corporate plans is consistent with the differentiating characteristics of each investor type, in particular, accounting and regulatory differences and the differing sources of sponsor capital that, at the margin, encourage a different risk management perspective.

In 2005, “underachieving your benchmark” was the most important market measure. Also, relative to the 2005 survey, “underachieving your benchmark” and “exceeding tracking error targets” dropped in importance more than any other response in this section. In contrast, only 50% of public pension funds and 39% of corporate pension funds said that “underachieving your benchmark” was “extremely important.” This represents an important finding because it shows a shift in approach away from chasing alpha and toward achieving specific targets since 2005.

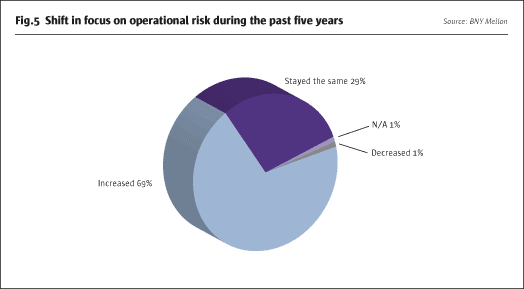

OPERATIONAL RISK

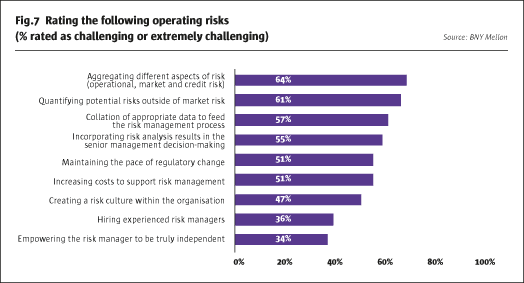

Operational risk has taken on new-found significance in light of the spectacular failures in the financial industry during the 2008 financial crisis. Although operational risk is not a new field, arriving at its definition can be challenging due to its complex nature. For our survey, BNY Mellon defined operational risk as the risk of loss from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems, or from external events. The Lehman Brothers collapse represented an excellent example of operational risk controls failing to identify underlying risks: specifically, the full extent of their sub-prime mortgage exposure, which quickly contaminated the whole financial market. Widely publicised trading losses, hedge fund scandals and, in general, much of the market collapse in 2008 could be traced to a lack of operational controls along different points in the investment process.

A close look at the events surrounding the 2008 crisis reveals the potential complexity of operational risk. Institutional investors will need to utilise a number of different solutions to safeguard their organisations from internal and external threats. These solutions need to combine qualitative and quantitative tools to tackle the different aspects of the industry’s operational risk challenges.

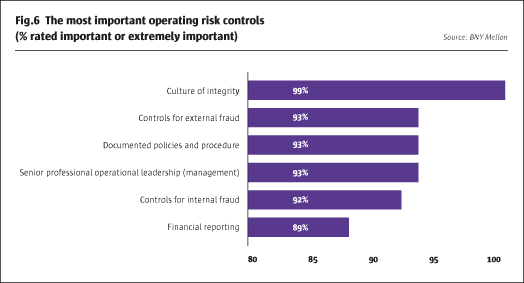

Operational risk management controls

The survey respondents utilise a number of different controls to monitor operational risk in their organisations, varying from a culture of integrity, to internal and external fraud controls, to financial reporting. All the categories scored very high, demonstrating an understanding of the importance, complexity and resources needed to mitigate operational risk (see Fig.6). Balance sheet strength and credit rating were the two most highly rated important risk factors when evaluating global custodians. Interestingly, stress test and SIFI status did not receive high ratings, possibly suggesting the 2008 banking concerns are now well behind us.

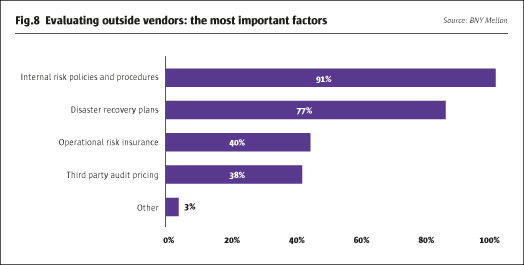

Operational risk insurance

Although the percentage of respondents actually utilising operational risk insurance went down from 35% to 26%, the number who ruled out operational risk insurancedropped much more and the number contemplating operating risk insurance rose from 5% to 18%. Furthermore, the number of respondents that now require operational risk insurance from vendors rose dramatically, from 7% to 23% since the 2005 Survey.

POLITICAL RISK

In our survey, we defined political risk as the risk that an investment’s returns could suffer as a result of political changes or instability in a country where instability affecting investment returns could stem from a change in government, legislative bodies, other foreign policymakers, or military control. Recent examples, such as the Eurozone bailouts, the US debt ceiling debate, and the Arab Spring protests, all had far-reaching and unintended implications to well managed portfolios.

Political risk as the trigger

Political risks can also manifest themselves in the form of regulatory changes or improper government oversight of laws. These events are sometimes thought of as one-off events that cannot be measured or predicted and do not rank as highly as market or operational risks in the minds of institutional investors, even though many political events have driven the volatility of markets. In fact, recent studies have shown that the most volatile trading days in US stock markets have been triggered by political events. For those operating in less developed countries, political risk may be predominantly operational in nature.

Referring back to our survey, 8% of respondents are not influenced at all by political risk when making an investment decision, and only 6% are extremely influenced. The focus on political risk has increased somewhat since 2005, where the average response has moved from 2.7 in 2005 to 3.1 (on a scale to 5) in 2013. Interview responses suggested this was because the respondents felt political risk, from an investment perspective, was primarily the investment manager’s responsibility. Only 22% of respondents believe time spent on political risks will increase over the next five years, and 75% believe it will remain the same or decrease, which shows that political risks are not thought to be a growing area of concern. On the other hand, exposure to emerging markets (where political risks are thought to be highest) has increased, with 66% increasing their exposure to emerging market equities and 39.8% increasing exposure to emerging market debt over the last five years.

Measuring political risk

Survey respondents largely rely on external resources (50%) and investment advisors (43%) to measure their political risk, with 36.4% stating they do not measure political risk at all. Political events can be difficult to predict and quantify. So with political risks not high on the agenda, but exposures to emerging markets and regulatory changes increasing, do we have the balance right? Many respondents indicated these decisions normally were the responsibility of the investment managers, but do they also have the right controls in place, or are the additional political risks taken by the investment manager offset by the larger alphas they gain? Given the influence politics and political events have had on market returns, credit ratings, regulatory enforcement, reserve requirements, leverage limits, transparency, business practices in areas such as the sub-prime lending market, and the ability of companies to compete on a level playing field, not to mention more serious turmoil that can up-end markets, it appears institutional investors are well advised to pay greater attention to political risks going forward. Institutional investors may want to, for example, spend more time evaluating their investment managers’ and advisors’ understanding of political risks as part of their normal due diligence and selection process and request regular reports from managers and consultants as part of their investment management process. For example, one respondent said: “Political risk is something we let our asset managers worry about and manage.” Another said, “we have a strategic system in place to look at their weights and their views, so that internally they can look at political and social risks, and adjust the portfolio.”

Legal and regulatory risks ranked the highest concerning political risk for survey respondents with 83% of respondents ranking it as important or extremely important, as they did in 2005, with currency inconvertibility and transfer restriction and confiscation, expropriation, nationalisation of the assets or of the company following closely.

To view the full paper please click here.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 93

New Frontiers of Risk

Revisiting the 360° risk manager

EXTRACTS FROM A REPORT BY BNY MELLON and HEDGEMARK INTERNATIONAL LLC

Originally published in the March 2014 issue