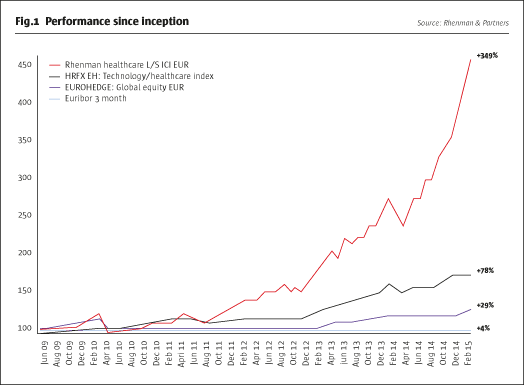

In early 2012, Henrik Rhenman told The Hedge Fund Journal “Either the world is approaching apocalypse, or we are due a massive rally” and he has been vindicated in spades: the Rhenman Healthcare equity long/short fund has delivered returns of more than 200% since the start of 2012. This has been achieved within a robust framework of risk controls. So Rhenman has not, for example, owned any of the pre-IPO private equity that has turbo-charged some funds and nor has he strayed from the fund’s liquidity criterion that 95% of the portfolio should be saleable within a week. Admittedly, it has recently been relatively easy to make money in long-biased healthcare investing because valuations in 2011 were extremely depressed, having dropped to single digit PE ratios in some cases. Healthcare has, to some extent, played catch-up and returns of over 150% make it the top-performing broad industry sector over four years to April 2015.

Yet Rhenman insists that the forces of secular growth and innovation are such that selected stocks can maintain the momentum for many years to come, and his own record of outperformance over his 20 years in fund management dates back to long before the recent sector surge. For instance his previous fund, Carnegie Global Healthcare, was the world’s top performing healthcare fund, advancing by 800% between 1998 and 2008, more than 40 times as much as the healthcare index, which was only up 20%.

Rhenman only invests in healthcare. The manager can invest long and short in all sub-sectors of the healthcare space, and all of them have appreciated in recent years, but biotech has done best of all – Rhenman has been well positioned to profit from value creation that he views as having a sound fundamental foundation. “Large biotechs have been growing sales rapidly while mid-caps have been executing on the R&D front and have also been involved in M&A.” reflects Rhenman, who has received takeover bids for some of his holdings, including Norway’s Algeta, which was acquired by Bayer in 2014. This corporate activity is important for the supply and demand balance within healthcare equities. If IPO volumes reached record levels in 2014, M&A in 2015 is also threatening to break records. In net terms, since 2011, the market has seen “four times more capital withdrawn from the sector through M&A than has been added through issuance,” says analyst and assistant portfolio manager Ellinor Hult. She finds this unsurprising because M&A deals are individually multi-billion – and in aggregate hundreds of billions of dollars – whereas most IPOs tend to be in the hundreds of millions or less.

Rhenman has profited from secondary-market biotech exposure, which has averaged around 40% of the fund, with selected holdings such as Incyte Corporation (INCY) and Esperion Therapeutics (ESPR) tripling or quadrupling over the past few years. Multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease specialist Receptos (RCPT) has done particularly well in 2015, partly due to takeover rumours. It is true that some biotechs have little or no sales or earnings, but roughly half of Rhenman’s biotech bucket is cash-flow positive and he typically invests after drugs obtain regulatory approval.

Amongst many facets of Rhenman’s risk management policies, position sizing is critical for earlier-stage companies and Rhenman does not risk more than 1% on a binary one-product company. “We will rarely have major drawdowns due to single company bets,” he says. While biotech stock picks have been a tailwind, at the same time Rhenman has had a headwind from a short biotech ETF position, used as a sector hedge and to reduce fund volatility – thougha single-stock biotech short was recently closed at a profit. Going forward Rhenman still finds compelling value in some biotechs and even thinks that the whole sector could be good value.

Is Biotech cheaper than the S&P 500?

The “disposition effect” in behavioural finance teaches us how investors have a bias towards taking profits prematurely, and this might lead some investors to think that biotech cannot continue to perform. Yet, despite the sector’s strong run of performance, Rhenman claims that biotech’s PE ratio based on 2017 profit forecasts, visible on Bloomberg, is still lower than that for the S&P 500 index. Moreover, Rhenman has several reasons for thinking that the consensus estimates are too low! “Many analysts risk-adjust too much for new approvals when they model, so they can upgrade estimates when they want to,” he explains, and claims that most companies beat the sell-side analysts’ probabilistic-earnings forecasts. Rhenman’s top five holdings in March include Biogen, which is developing treatments that may slow the progression of Alzheimers disease by attacking plaques in the brain. As well as being overly conservative on approvals, the sell-side earnings estimates completely ignore likely M&A, which Rhenman expects to continue. In summary, Rhenman thinks the sector performance is being driven by solid fundamentals.

Notwithstanding the strong prospects of biotech, Rhenman does see sector leadership shifting to other industry segments. Big Pharma is a sub-sector that contains companies with a multi-year runway of growth. Immuno-oncology is one very promising area of research that has already discovered therapies for skin, kidney and lung cancers that can supersede the previous treatment approaches, which revolved around surgery, radiation, first generation antibodies, chemotherapy – with attendant side effects. New treatments that delay cancer progression by a number of years are now a major breakthrough, as the human immune system is assisted in re-launching its attack on cancers. The fact that only around 25% of patients have responded positively to some drugs in trials suggests that combination therapy may improve response rates and years of further research lie ahead, according to Hult.

“We don’t just hold stocks for the next quarterly report as it could take one to three years for pipelines to play out,” explains Rhenman. That said, he might still trade around positions over inflection points and events. For instance Shire Pharmaceuticals has long been a core holding and after the takeover offer from Abbvie fell through, Rhenman took the opportunity to add to his holding. Less than one year later Shire’s share price has already surpassed Abbvie’s offer. Rhenman’s top five holdings in March 2015 also included Novartis of Switzerland and Bayer of Germany. Danish insulin maker Novo-Nordisk has been a strong contributor in 2015 after it gained approval for a new form of a diabetes drug, Saxenda, that may help to address the obesity epidemic, but the company is also a winner on the rise of the dollar.

The one area of big pharma that Rhenman tends to avoid is generics, as even the largest players such as Teva have had growth problems, which may be one less benign reason for mergers in the sector. Even when generic makers are located in some of the most exciting emerging markets Rhenman still finds they do not meet his quality criteria. “Organic growth is hard to come by because the products’ lifecycles are much shorter at only six months before exclusivity periods end,” he points out.

Ultra-lucrative orphan drugs

Yet the obverse of the generic manufacturers’ challenges is that industry dynamics are vastly conducive to highly specialized biotechnology companies. The orphan drug paradigm is the core driver of growth here. A generation ago the pharma-industry was based on blockbuster drugs, such as painkillers, blood pressure and cholesterol lowering drugs that charged low prices to huge populations. Nobody thought it would be worthwhile to develop drugs for smaller populations and Rhenman recalls how Sweden’s Astra even questioned the viability of the biotech industry, years before it merged with Britain’s Zeneca. But biotechs were quietly researching neglected opportunities where they might charge as much as $30,000 per year for patient populations as small as 20,000.

Genzyme’s treatment for Gauchiers’ disease marked the first new departure, and the addressable market turned out to be many times greater than the original estimate as hospitals recognised the value of the treatment. The fact some drugs freed patients from needing constant care enhanced their pricing power. Although the commercial value of orphan drugs is now widely recognised, there is still much to play for. Rhenman thinks there may be 1,000 diseases, each of which could be treated with drugs generating average revenues of $200 million. What makes orphan drugs special is the lack of competition. Populations are so small that companies can easily obtain a first-mover advantage and, to borrow a phrase from Warren Buffet, the “moat” around these firms is getting stronger for other reasons.

Intellectual property protection is growing simply because it is much harder to copy more complex products, from several angles. Longer and more complex molecules increase the manufacturing challenge of copying a drug but that is not where it ends. The documentation requirements are another barrier to entry, as firms need to demonstrate through clinical trials that their treatment is identical to the original version. For orphan drugs there is also a very practical constraint of being able to locate a sufficient number of people with rare diseases who are able to participate in trials! “Accessing orphan populations is a major barrier to entry because incumbents have already done the legwork,” says Rhenman. There are some investors who beg to differ and activist investor Kyle Bass is pursuing a highly contrarian strategy of disputing pharma patents. Rhenman thinks Bass might win one or two cases out of a dozen, but more importantly Bass will create volatility and uncertainty with good entry points for longer-term investors.

Insight into the prospects of new drugs and treatments comes partly from Rhenman’s Board and the Scientific Advisory Board. The Board is chaired by Hans Wigzell, erstwhile Rector of the Karolinska Institute where he is still a Professor, and former chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Wigzell is an expert in immunology. The Scientific Advisory Board members each have their own specialisms including: oncology, metabolism and endocrinology; autoimmunity and nervous system diseases; and surgery and clinical services. “The scientists help us to understand the science,” says Rhenman. More specifically “they weed out companies that are hard to assess where it is too early to make an honest assessment of inherent value”. For instance gene therapy is at a much earlier stage than immune-oncology, although there is already proof of concept for some genetically-caused enzyme insufficiency disorders and certain types of blindness and other ophthalmologic diseases, thinks Hult. The advisory board has added one new member over the past year and may add another one over the next year.

The Rhenman team hold hundreds of company meetings each year and have often been following firms for a decade or more. Even after whittling the universe of new companies down to 30 candidate names, Rhenman proceeds cautiously by scaling into positions, which may start as small as 0.4% of the fund. The highest conviction positions can grow as big as 10% but with 150 positions, most are below 1%. The relatively conservative approach is also seen in that a 6% drawdown prompts a formal risk review, and often some risk reduction, something that has happened several times over the fund’s life.

Obamacare boom for hospitals

Moving away from the three drug-oriented sub-sectors (large pharma, speciality pharma, and biotech), Rhenman covers the whole healthcare space. In terms of stock market performance, second only to biotech has been distribution and services, which includes managed care and hospitals. “The cash generation of insurers and hospitals is huge and they are operationally leveraged to the improving world economy,” enthuses Rhenman. Earnings per share have been growing as fast as 20% annually. In the US profit-making hospital chains are taking market share from less efficient non-profit ones and Obamacare is encouraging insurers to give more business to the most efficient operators. The sector is very US centric but there are some European plays such as Fresenius. Emerging markets are where Rhenman tends to avoid healthcare services as they trade at a scarcity valuation premium.

Medical Technology is a small allocation for a different reason – it is a late-cycle play. Rhenman recalls how it can take hospitals and surgeons years to upgrade procedures and adopt new technology, whereas drugs are much more immediate. As well, many med-tech firms face a headwind from the stronger dollar.

Secular growth story continues

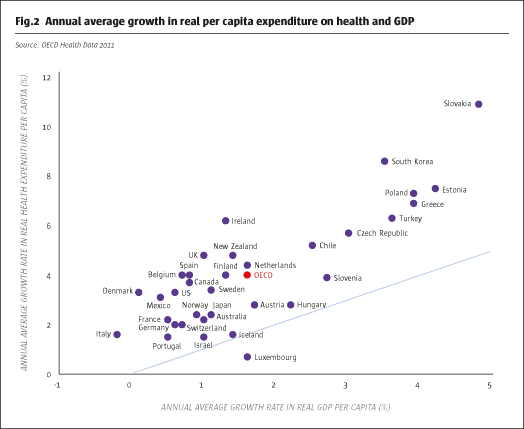

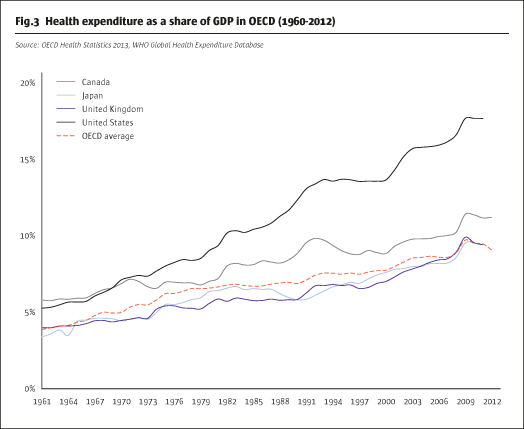

While the relative merits of the sub-sectors move around with valuation and cyclical patterns, the one constant is that the entire healthcare sector is growing faster than the economy. Rhenman has long argued that healthcare is a secular-growth sector, and equity markets are beginning to recognise this. Between 2000 and 2009 spending on healthcare grew at twice the OECD GDP growth rate. Despite austerity in a handful of European countries “this is not going to change in a recession as the needs of humanity are so clear,” opines Rhenman.

Demographics are one source of growth as populations age. But what matters more for Rhenman is innovation allowing more diseases to be treated and treated more effectively. Rheumatism is one example where sufferers that were once confined to wheelchairs are now mobile. Rhenman also observes how, as societies grow richer, they can devote a growing proportion of GDP to healthcare, so this could rise from 10% to 15% or even high teens. If pharma-market growth of 12% in the US in 2014 was unusually high due to new treatments, Rhenman still sees high single digit growth rates of around 8% this year and next. That figure can be doubled in China where Rhenman is projecting 15% growth rates. Emerging markets in general are a clear growth story, but one where locally listed firms may not be the optimal way to play as they are often generic makers. Rhenman prefers to own developed-market healthcare firms, which are getting as much as half of their growth from emerging markets.

One thing that cannot be sustained indefinitely, however, is the scale of inflows into the fund, which has grown from $50 million to $500 million since 2012; while around $150 million of this represents the stellar investment performance we can infer that there have been net inflows of around $300 million. Rhenman estimates capacity for the monthly dealing, Luxembourg AIF, at $1 billion based on the amount he ran at Carnegie. With assets already over $500 million, Head of Sales and Marketing Carl Grevelius says that Rhenman intends to soft close the fund in October of this year, meaning that only existing investors would be able to add to their holdings from that date.

The capacity target is relatively conservative because Rhenman likes to maintain an even balance amongst large caps, mid-caps and small caps and sticks to the liquidity constraint of being able to sell down nearly all holdings within a week. He also acknowledges that the short side of the book is more capacity-sensitive than the long book. But for the time being Rhenman clearly expects the longs will continue to be the main locomotive of returns.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical