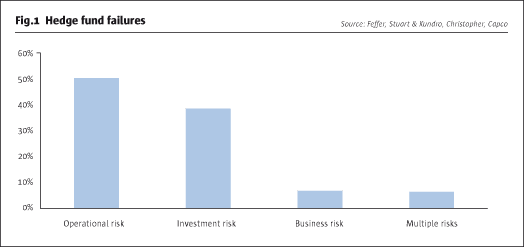

As a primary focus, investors desire a specific return for a given level of risk and liquidity profile. However, understanding the threat and significance of operational risks may prove more important, as shown in Fig.1.

Operational risks are caused by people, processes, systems and external events. If pre-investigations commonly known as “operational due diligence” do not take place to reveal the significant operational risks, the investor may find themselves with far more concerns than just simply a reduced rate of return. Here are just seven “avoidable” situations investors do not want to find themselves in.

Getting money back on fund closure

Some fund closures can be anticipated, particularly where one large investor or a group of investors redeem their investment following a period of bad performance. The initial consequence of unanticipated large redemptions can lead to Net Asset Value (NAV) per share being reduced if an anti-dilution levy is not in place to compensate the remaining fund shareholders. A final decision to close the fund could lead to closing trade positions at sub-optimal pricing. In another and perfectly feasible scenario, two founding individuals may leave the fund’s management. The remaining team may lose confidence because key leaders have left and decide to close the fund.

In closure situations investors may be notified that the fund administrators have invoked a freeze on assets under fund rules whilst all the fund’s current and accrued liabilities are met. To make matters worse you could be burdened within unexpected liabilities placed on the fund in a forced closure situation resulting in a significantly reduced redemption position, a lot less than you expected and not just due to a lack of fund performance. A check on the investor base, key individuals, key person insurance and employment contract terms, plus a detailed review of all fund legal documents for closure terms may have resulted in a non-investment decision had more facts been revealed.

A fund closure can happen quickly. For example, a serious compliance event can lead to a regulator forcing a fund closure. Even without regulator intervention, public knowledge of the event will lead to a reduction in investor confidence and subsequent redemptions leading to the fund having to be closed down. In today’s market, a regulator just has to say an investigation is underway for investors to redeem on mass. It is important that the compliance function is very active in monitoring fund activity to comply with financial regulations; adverse information does not take long to reach the public domain, leaving the reputation of any fund in ruins. Liquidity can also reduce and delay investor payouts.

Altered valuation to hide loss

Unfortunately this does happen and more often than you would expect. Oddly enough, large fund institutions are not immune. Although they may have supervisory procedure by a separate department function in place, adherence to procedure can be lost due to increased trading volumes, available staff resources and/or simply a lack of staff discipline. For example, an over-valuation occurred at a large financial institution where back office procedures were not properly performed. The discrepancies arose from a deliberate action by trading staff not to mark over the counter positions to market – an omission which was also not identified by the secondary party designated for oversight. Independent valuation of trading positions was inadequate and there was significant and widespread non-compliance despite internal controls. The message here is that investors in hedge funds need to get assurance on valuation procedure. Managers consulted on valuations by administrators should not decide on valuation sources nor determine new valuation procedure without independent fund director oversight. In fact, the good fund manager would have a process in place to ensure valuation is always transparent and that final NAV is always completed by an independent administrator.

A deliberate action to misrepresent the value of positions is a regulatory offence and will attract large fines on the fund manager, not to mention the massive readjustment to the NAV of the fund to the detriment of the investor. It is likely that such an event could also lead to a forced closure of a small hedge fund.

Inaccurate performance report

The monthly calculation of the NAV per share of a fund (value of a fund share after charges and expenses) is the quoted value to indicate the performance of a fund. An administrator that has a NAV procedure where a formula-based valuation calculation is consistently not correct and the error was not found due to inadequate cross reconciliation with fund manager estimates could lead to an inaccurate reflection of fund performance. An accurate NAV calculation could reveal what initially appeared to be an increasing return and favourable investment situation to be in actual fact a poor performing fund. In this situation the investor may have redeemed their investment months earlier if they had known.

Poor hedging gives big drawdown

An investor may have invested because they liked the investment strategy but did not thoroughly examine their ability to deal with investment risk. Without adequate trading checks, segregation of the investment risk management function or clear risk procedure, devastating trading losses can be made. For example, many trading strategies may have a number of trades to be executed in order to hedge and safeguard position(s). If for instance they could not be completed in an adequate time frame, a market event could damage what would have been a very positive situation. Manual trading strategies need to have adequate checks to ensure trades are completed as expected. Other trading losses can occur if a trading risk management strategy is not adhered to closely. Without risk monitoring, a single position that goes beyond a set limit can be missed, again with damaging consequences. The pertinent point here is that the implementation of investment strategies is as much about strong risk management and adequate operational controls as it is the good investment idea.

Cash transfers go missing

Many trust and fiduciary service providers exist which on the face of it have adequate wire transfer controls. However, this is not a complete safeguard against theft and fraud. In small niche service providers, detrimental criminal collusion between signature authorities may occur whether the entity is regulated or not. Some investment funds fail to remove possibilities of theft or fraud either by a detailed examination of service provider procedures or the introduction of another signatory or independent third-party authority where needed. The result being that the fund is still at risk from theft or fraud.

For example, a fund set up to invest in land may use a small trust service provider to execute land purchase agreements as dictated by the fund manager. Such providers often have access to large sums of money sent by the fund administrator or from sold investments for short periods. Two local authorised signatures for asset transfers at the office of the service provider may not be a sufficient control; it may be wise for the fund manager or a totally independent third-party to act as a counter signatory to completely protect investor assets. A prior statement provided to an investor by the fund manager promoting the good credibility of a small fiduciary service company is no safeguard for the investor against a theft of cash that could still occur due to staff colluding in the organisation. At the very least, due diligence should cover a close examination of a service provider’s financial controls and produce firm statements on what is wrong and what must be done if investor’s assets are at risk.

Erroneous prices

Unfortunately for the hedge fund, this investor was made aware of why a number of trades in a systematic managed futures trading system took place based on a false trend signal caused by price errors in the market data feed. Even though the error was discovered, loss had already been incurred due to the reaction of these future positions to an external market event. It would be normal in such systems to have a second or third price feed in order to check input prices. However, in this example, although this system did have a secondary feed, it was unavailable and the system allowed a single price feed to drive the system; price tolerance checks in the system were later also found to be insufficient. The method-based operational due diligence analyst correctly examines technology disaster recovery facilities, but do they look closely at the system design, testing and change controls? The answer is probably not!

The message here is clear: concerned investors need assurances that the operational due diligence analyst has closely examined a systematic trader, their technology infrastructure and system controls. Investors understand a hedge fund protecting its trading intellectual property, but correspondingly many of the failures occur through weak system design, system operational controls or inadequate system change control; more transparency is needed not less. In fact, it is known that the biggest enemy of a systematic hedge fund’s trading availability is technology staff performing changes in an uncontrolled manner. It is also likely that many financial losses occur due to uncontrolled system changes. The good larger fund manager will carry losses due to self inflicted system operational failures themselves and not penalise the fund, but this is not always the case and NAV could be directly impacted.

Hidden fees via service provider

In this scenario, the manager of a land investment fund just happened to be the sole owner of an associated offshore land administrator trust provider servicing the fund. Although none of the fund manager principals were directors of the land administrator trust, they clearly had a controlling shareholder interest and dictated fees for the service. Such a vital detail was absent in the fund offering memorandum; the fund manager due diligence questionnaire (DDQ) also conveniently missed out this fact. In the operational due diligence world this could be interpreted as being “economical with the truth”, consequently misleading the investor.

This situation was not mentioned by the external auditor who did not question the high fees of the land administrator trust. It is not the auditor’s principle objective to check fees; however, one would expect them to make sensible observations. On the face of it there is nothing illegal here. However, the manager was using the service provider opportunity to effectively derive more unpublished earnings at a level he could determine. The end result for the investor, a lowering of NAV per share which would have otherwise been 1% higher. To mask this hidden earning potential, this fund manager went out of their way to demonstrate to the due diligence analyst how good they were at segregation: independent administrator, independent reputable auditor and statements in the DDQ about no access to fund assets whatsoever by the fund manager. However, with this fund structure deception revealed, the investor should ask what else might this fund manager cover up and in what circumstances?

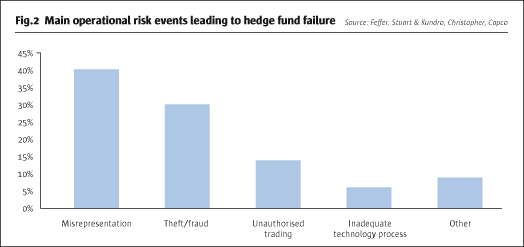

Conclusion – operational risk events

The above situations are all about operational risks. An historical measure of the main operational risk events leading to hedge fund failures is shown in Fig 2; misrepresentation being the main cause for concern. Investors need to consider that even a small series of events could affect their investment return. Just seven operational risk situations have been described above, but there are many more. There are those few fund managers who for whatever reason choose the route of deception, theft and fraud and not the route of honesty and transparency. Even new structures to protect investor assets combined with change can open up opportunity for those inclined to abuse investor interests. Operational due diligence should be much more than methods, scorecards, comparisons and statistics. The due diligence analyst needs the mind of a detective and real fund industry experience to illicit the risk that can matter to an investor. Like a detective starting with method, an ability to drill down in suspect areas and apply the right analysis skill is required.

Operational due diligence could be considered a cost without reward; it certainly could be a regret for investors who do not give it due attention and an unrevealed risk leads to investor loss. For those fund managers who are committed to transparency in the post-Madoff era and have a positive attitude to mitigating operational risks, aspects of operational due diligence revealed by investors may assist them in avoiding unnecessary losses. The astute hedge fund manager can use their good management of operational risks to attract investment. Investors require more transparency, not less, and clear messages when there is clearly something wrong to stop investment going forward. Operational due diligence warning areas highlighted could be indisputable red flags for some investors or alternatively become recommendations that investors can put to fund managers to clean up their act as a prerequisite to investment.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical