Investors holding ‘traditional’ long-only multi asset portfolios have enjoyed a fantastic environment so far in 2019, with asset returns running contrary to highly pessimistic narratives about the state of the world. Once again, many macro hedge funds and other hedge fund strategies have struggled by comparison, and are facing renewed challenges to justify their role in modern portfolios. Yet, far from invalidating the case for macro strategies, a proper understanding of developments so far this year only strengthens the case for flexible and differentiated approaches.

Year to date 2019: strong returns and confused narratives

The year to date has profoundly shocked many expectations. In the face of mounting recession fears, trade wars, and what the IMF calls a ‘synchronised slow down’, most major equity markets are up double digits. At the same time, developed market government bonds have also delivered strong positive returns not seen since 2014. This has been a source of profound confusion for those wanting to characterise the environment as either ‘risk on’ or ‘risk off.’

The economic backdrop is far removed from where it was eighteen months ago. As recently as October last year, the key question seemed to be how high US rates could go, not how many more cuts the economy would need. Only slightly earlier in 2018, the growth narrative was one of ‘synchronised expansion’, not late-cycle imminent recession.

The year to date has profoundly shocked many expectations. In the face of mounting recession fears, trade wars, and what the IMF calls a ‘synchronised slow down’, most major equity markets are up double digits.

No investor with any experience should be surprised to see economic beliefs confounded so dramatically. Such shocks are nothing new or unusual; they are the normal state of affairs even if our brains refuse to believe it. What is more interesting is the confusion surrounding how assets have performed against this backdrop.

Correlated positive returns in equities and bonds so far this year run counter to the mental models that many of us have of how asset prices behave: the positive return on risk assets seems inconsistent with the pessimistic mood-music of data and commentary, and sudden shifts in ‘value versus growth’ or the outperformance of the US banking sector do not fit conventional narratives.

In keeping with much of the commentary since the financial crisis, such moves are seen as something that ‘shouldn’t happen’, a function of a world that is ‘broken’, and a distorted financial system. There is often an underlying anger and frustration in many attempts to characterise what has been going on.

The role of rating

Such confusion is a manifestation of how the world is presented to us. Most of the investment commentary we see day-to-day on outlets like CNBC or Bloomberg has described short term price moves through the lens of either ‘intensification’ or ‘lulls’ in trade war fears, speeches by Central Bankers, or the President’s tweets.

But these ‘news-led’ interpretations are incomplete at best. Very little commentary seeks to explain market moves in terms of how assets are valued, and what it is that prompts the market en masse to re-rate or de-rate assets. Moreover, even when policy makers dominate the headlines, it is moves of 25 basis points here or there in policy rates or quantitative easing announcements that often gain the most attention, even as government bond yield moves of 100s of basis points are given less airtime.

In an article in The Hedge Fund Journal, April 2018 (Volatility is Back, But This Time it’s Different) we sought to redress this imbalance in commentary. In that article we wrote about the central role played by asset valuations, and in particular the global risk free rate, which acts as a “correlating force” that can “create price shifts and volatility that are not a function of ‘news’ as such; but merely of changes in perceptions of risk, and how investors believe they should be compensated for it.”

As it proved in both February and October 2018, it was rising rates in the US that drove markets, prompting equity losses. And by the end of that calendar year, many were surprised to find that few, if any, major asset classes had delivered a positive return.

However, following the ‘risk off’ episode in November and December of 2018, and over the course of 2019 to date, it has been the collapse in global real rate structures, rather than rate increases, that has dominated.

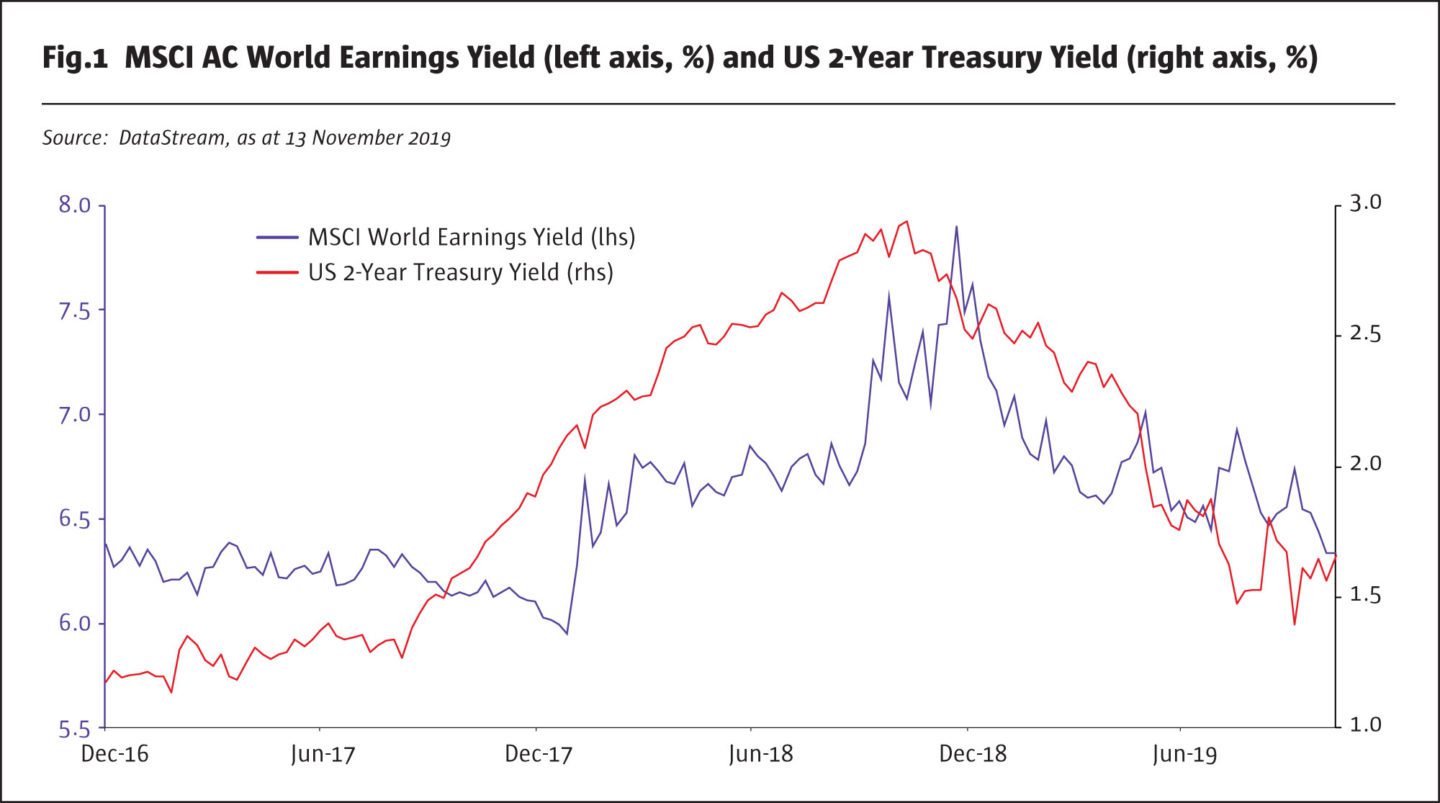

This can be seen in Fig.1; it shows the US two-year Treasury yield against the earnings yield for global equities. As US short rates rose in 2018, global equities de-rated (the earnings yield rising as the p/e fell). As short rates collapsed over the next twelve months, this was reversed.

It is this dynamic that accounts for the positive returns across assets we have seen so far this year. Moves in 2018 (both the shift in real rates, and the episode of myopic panic that dominated in December) served to increase the prospective returns on a range of assets, and equities in particular.

In 2019, it has been the re-rating of ‘risk assets’ against the backdrop of falling rates and the unwinding of that December episode that have driven positive returns, swamping any negative effects of weak earnings news or pessimistic growth outlooks.

Pivotal moment, part two

This dynamic has resulted in a highly fertile environment for plain vanilla long-only multi asset funds. Correlated gains across assets over longer periods have been accompanied by negative correlation when you have most needed it, with bonds acting like an insurance policy that also pays you handsomely over longer periods.

In fact, it is an environment that has been in place for much of the last thirty years and especially since the financial crisis. For all the talk of complicated strategies to manage volatility, mitigate tail risk, and generate ‘uncorrelated’ returns, it is the traditional mixes of equities and bonds that have delivered the types of return profile many have been crying out for.

And yet this environment is not a sustainable one. While the decline in global rates has gone far further than almost anyone would have expected, this does not change the fact that it is a finite game: all capital gains from fixed income assets are ultimately borrowed from the future, and the ‘return tailwind’ from ongoing rate declines can only go so far. Prospective sustainable returns are now close to zero.

This was a point we made in an article (A Pivotal Moment?) we wrote in June 2016 for The Hedge Fund Journal, the last time global rates were at similar levels to those prevailing today. In the period following that article we saw poor returns from bonds (from the middle of 2016 until the fourth quarter of 2018), correlated losses from long exposures to most asset classes in 2018, and, until very recently, disappointing returns from many macro hedge funds and other strategies which had sought to hide from volatility or equity correlation (see The Wrong Type of Macro? written by us for The Hedge Fund Journal in July 2017).

Over the last twelve months, the favourable tailwind that existed prior to 2016 has been reasserted, ‘granting a reprieve’ to approaches which had struggled in the prior two years. However, this only takes us back to the playing field as it looked in 2016, with high realised returns only serving to increase the chances of low prospective returns.

Many acknowledge this, and much has been written this year concerning the ‘death of 60/40 funds’, often citing the low prospective returns on bonds, their diminishing diversification properties, and the greater volatility of important areas of the fixed income market.

This is not to say that we should expect a reversal of fortunes imminently – the fact that such arguments are so widespread is probably reason enough to be sceptical – yet it is hard to argue that bond valuations suggest anything other than far lower returns, even in supportive environments, than those many of us have become used to.

Is cash your only defensive asset?

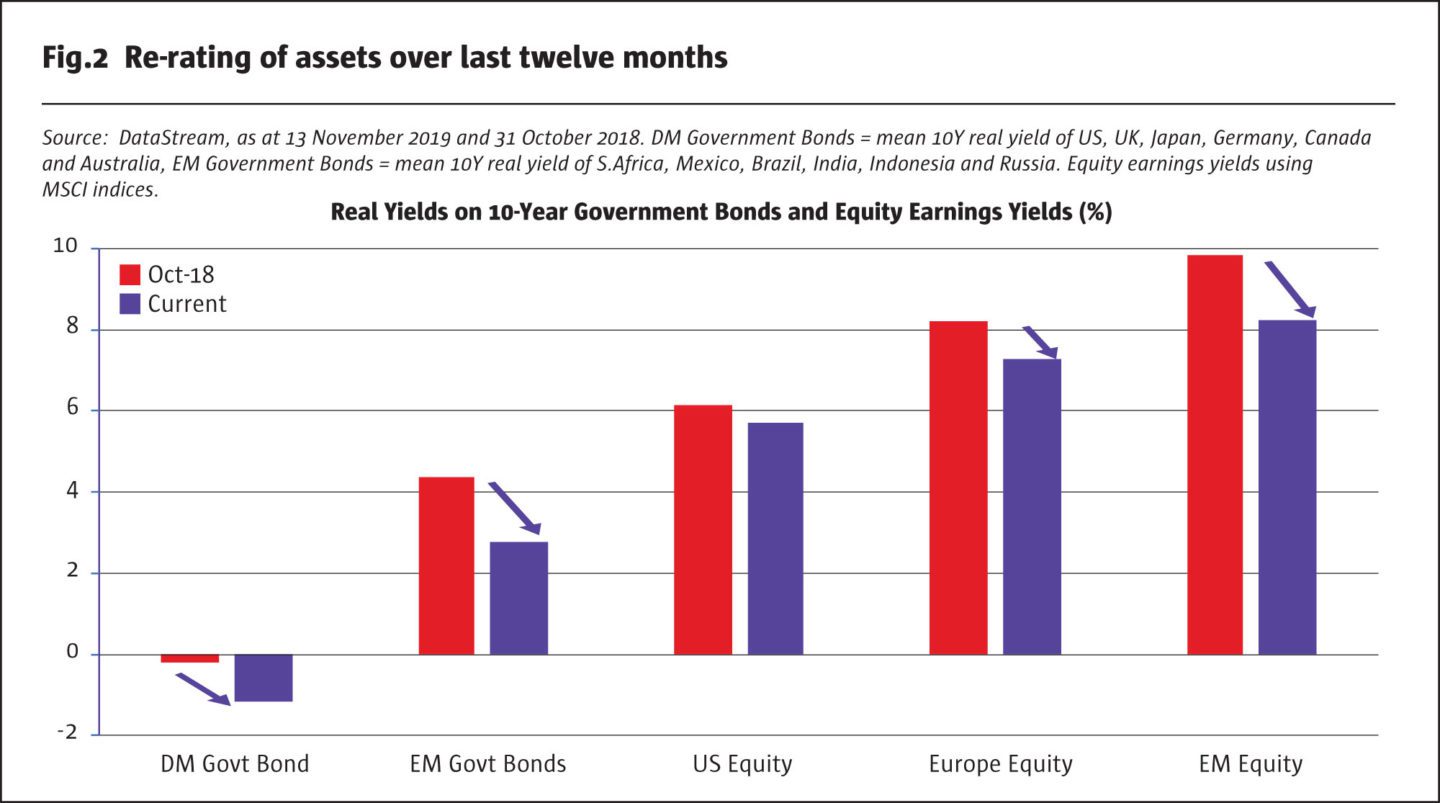

The re-rating of major financial assets since October 2018 can be seen in Fig.2 which shows the real yields (using consensus long term inflation expectations) on selected 10-Year government bonds, and the earnings yields on the MSCI indices for the US, Europe ex-UK, and emerging markets.

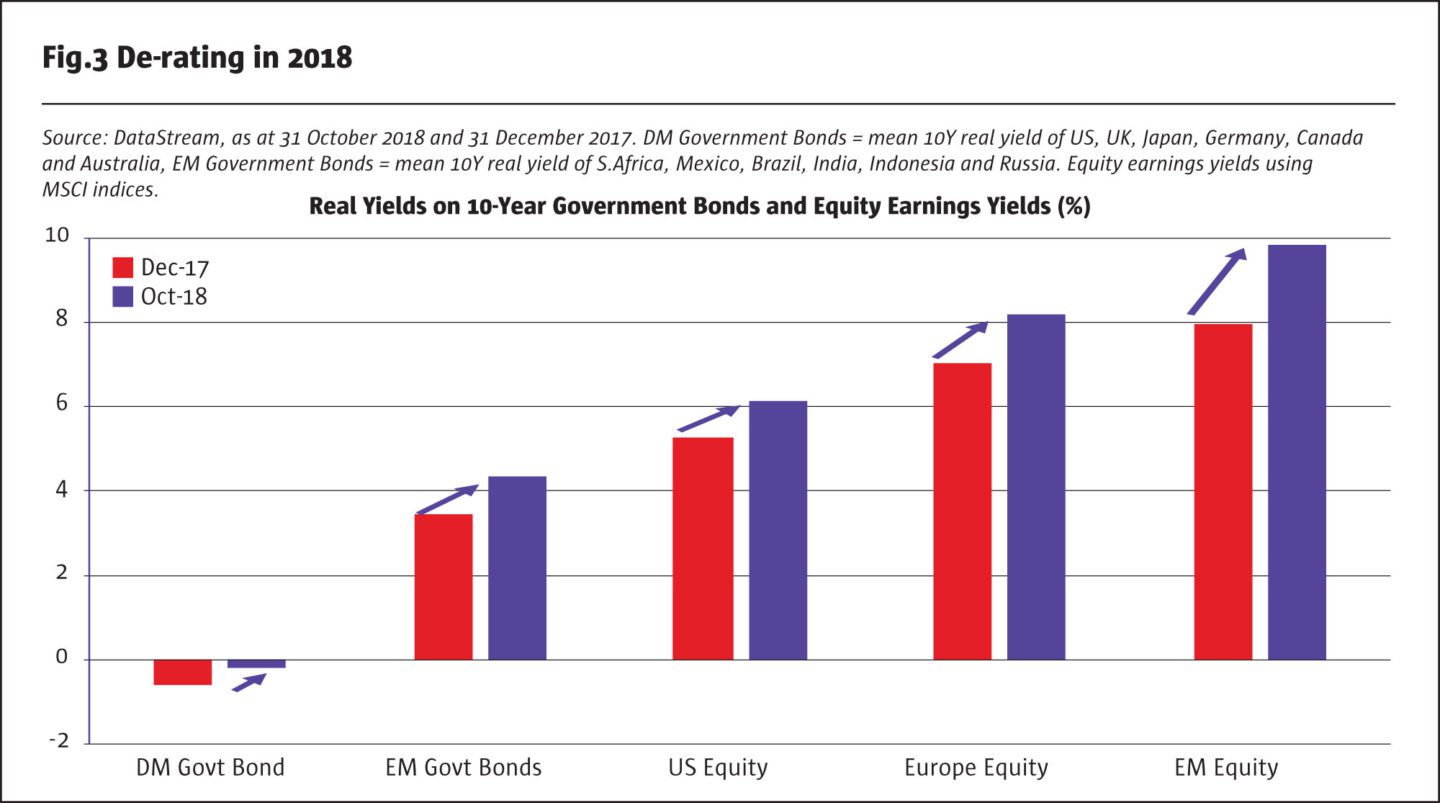

As rate expectations have declined, so conventional value metrics have become less attractive almost everywhere. This suggests not only a greater likelihood of worse returns in the future, but also vulnerability to reversal. Compare Fig.2 with de-rating of assets that took place up to October 2018 (Fig.3) where the dynamic is reversed.

In this rising rate environment, it was possible to generate positive returns in equity markets that grew their earnings (most notably in parts of the US), but otherwise there was nowhere to hide for long-only investors. Traditional assets held for capital preservation failed to deliver. In emerging markets, not only did assets deliver negative returns but currencies also weakened sharply. Approaches without significant flexibility were left with cash as the only option to preserve capital. Today, we appear to be at a similar juncture.

It is in just such phases that those very hedge fund strategies that have been criticised for failing to keep up with global equity markets, or even traditional balanced funds, have the flexibility to deliver positive returns. This may be through the use of shorting, targeted exposures, or dynamic market timing. For others seeking the ‘holy grail’ of high returns with low volatility and low correlation to growth assets there are far fewer options.

Does this mean that the world is ‘broken?’

For those who view global financial markets as rigged by Central Banks, this is a troubling situation. And yet, for all the conspiracy theories it is hard to quarrel with permanently lower rate expectations from an economic standpoint. The inflation that many thought quantitative easing would unleash has yet to transpire, to the extent that few admit to having ever made the argument. In fact, the economic system has been one in which no matter what you throw at it, whether it be commodity price booms in the early 2000s or ultra-easy monetary policy, aggregate outcomes have been benign.

A key difference between the landscape today and that of summer 2016 is that many areas of developed equity markets are now ‘expensive’ or fully valued.

From this perspective lower bond yields do not seem inappropriate and the only real distortion is in negative policy rates, the effects of which are now being challenged by academics, policy makers, and politicians.

At the same time, it is no contradiction to say that, while lower rates than prevailed in the 1970s to 90s are justified, it can still be the case that that prospective returns to bonds are low and vulnerable to deeply negative outcomes, just as they were in 2016.

We should also be wary of believing that a low rate environment is synonymous with weak earnings growth. Many have conflated lower rates with a secular stagnation thesis, but this can be a dangerous assumption. While we cannot know the counterfactual, it has been the case that very low rates can run side-by-side with strong profits growth, as we have seen in the US. Profits growth can allow equity returns to be positive even against de-rating caused by rising rate expectations.

So long, long-only

Once again markets appear to be at a critical juncture. A key difference between the landscape today and that of summer 2016 however, is that many areas of developed equity markets are now ‘expensive’ or fully valued. Whereas the post 2016 environment allowed for returns if one was willing to simply tolerate the volatility that comes with risk assets, it seems more likely that the flexibility to short, and a high degree of selectivity will be more important than it has been for some time.

As macro investors, we will seek to stay true to our approach of the last twenty years: acknowledging that the world is a profoundly surprising place, and from this position of humility seeking to capture sustained trends in asset class returns. Doing so will require more than simply maintaining a static bullish or bearish view, a passive long exposure to a range of assets, or pandering to the idea that high returns can always be generated with low volatility and low correlation to growth dynamics.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 145

The World is Not Broken, Nor is Macro

2019 developments highlight greater need for flexible approaches

Dave Fishwick, CIO, Episode, Macro Investment Business and Stuart Canning, Episode Investment Team, Macro Investment Business, M&G Investments

Originally published in the November | December 2019 issue