There has been a great deal of commentary and discussion recently about the struggles experienced by macro funds. As Fig.1 highlights, fund returns over the last five years have been relatively low in an absolute sense, but most notably relative to global equity markets. This reality and perception has intensified over the last twelve months after the sea change in market behaviour seen in mid-2016.

Amongst many, there have been two primary and related attempts to understand and explain this disappointment. The first argument is essentially that ‘macro’ as a strategy is based on economic forecasting, that forecasting is a built on pseudo-science and, as such, we should never expect macro strategies to work consistently. The world is a dynamic and complex place and systematically “getting it right” utilising superior forecasting insights is extraordinarily challenging… even if it is fun trying!

The second perspective is a more specific observation on the current environment; it points to the effects of QE and holds that macro managers have either simply been ‘wrong’ in not simply backing the obvious upward trend in equity markets that would result, or that the distortionary effects of central bank policy has made forecasting macro trends impossible. This view implies that when things are “normal” forecasting is likely to be more successful. The evidence for this is not compelling and the concept of “normal” of itself is highly questionable.

Whilst superficially attractive, these arguments are partial explanations at best. More important is in how the interpretation of macro returns illustrates a profound change in collective psychology over the last twelve months. As I wrote in The Hedge Fund Journal in June 2016 (“A Pivotal Moment”), investor behaviour is at the heart of this, with the major shift taking place in risk perceptions, and in particular a renewed prioritisation of absolute returns over volatility dampening or negative equity correlation. In short, investors used to look for one set of outcomes in macro strategies and are now looking for another.

Defining macro

A key part of the challenge is the labelling and definition of what macro strategies are or should be. This relates to the assets that strategies invest in, along with beliefs about volatility and correlation with selected asset classes. A static view of what is “appropriate” and one which fails to acknowledge changing market regimes and asset valuations, although superficially attractive, is a dangerous one to adopt and can be the source of major problems. The decision relating to “what do we want a macro strategy to achieve” is far from simple. It is often relegated below other considerations in many discussions and there is a tendency for that decision to be based on temporary and dangerous partial truths.

A second observation is that in the world of discretionary macro, it is far from obvious that investing must necessarily go hand in hand with economic forecasting. Sustaining an edge in economic forecasting seems highly problematic and is something that has proved elusive for the vast majority. Worse, perhaps, is the reality that economic fundamentals are only one element of asset price behaviour and returns. Often more important as a driver of returns, are the role of the starting point of valuation and the impact of shifts in investor emotions. Incorporating these ideas into what we understand by macro could also be helpful.

In a recent financial news article, one macro manager noted with frustration the times when he “got his forecasts right but market predictions wrong.” To our mind, this is not a function of today’s “non-normal” environment, but the normal way of things. Although they are frequently ignored and permanently underestimated, it has always been the case that perceptions of risk and the starting point of value are periodically far more important than changes in the underlying fundamentals.

Macro is a broader category that covers any form of discretionary top-down investing, across a wide range of possible asset class exposures. Not all macro managers will be economic forecasters and not all will conform to a narrow view of “typical” exposures and strategies. The apparent failure of some funds to deliver desired returns in this environment is not exposing the flaws of macro as a strategy, because macro is not a single strategy, but a broad umbrella term encompassing a wide range of investment approaches.

So what is really going on?

Ultimately, the more recent failure of many macro funds to meet expectations is a function of the same type of thinking that has permeated the investment industry since 2000 and became more acute in the period after 2008. For much of the last ten years many investors adopted a perspective that short run capital preservation should take priority over generating higher returns in the medium term. Having been brutally reminded of the risks that can go hand in hand with equity and credit investment, investors have been terrified of short term volatility. This has been true even where it proves temporary and is only an irritation on a journey toward attractive returns.

Because macro allows for flexible “go-anywhere” mandates, investors have therefore put a premium on anyone that can demonstrate negative correlation with equity (or in some cases, with all traditional assets classes). Macro became associated with strategies that protected, or better still were negatively correlated with “risk” (where risk is taken to mean abrupt capital loss, even when it is temporary). This equity and volatility “aversion” has been the convention, bordering on an obsession, and negative correlation has been seen as the “Holy Grail”. Macro managers were incentivised – and made to feel clever or popular – by avoiding risk and demonstrating an ability to make money out of drawdown phases. Any hint of a willingness to generate returns via longexposures to “risky” assets has been seen as a weakness, even when those returns proved to be superior.

A transition?

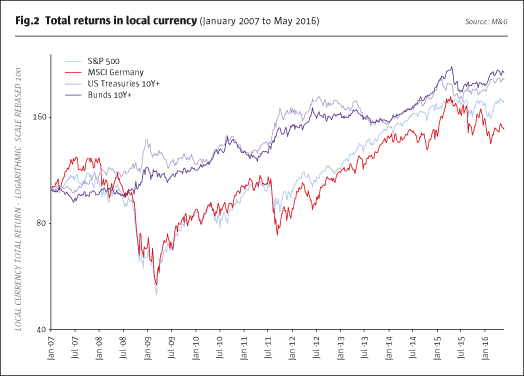

Given these circumstances, it should come as no surprise that many macro funds will have generated returns in line with “safety-oriented” assets, which since 2012 have not been particularly attractive in many cases. They certainly will not have kept pace with equity markets – that is simply not what they have been incentivised to do.

As human beings, it is in the nature of investors in strategies that have an absolute return mentality that their benchmarking or assessing “goal posts” move over time, even if they don’t realise or want to believe it! Having now gone through a phase in which the “risky” assets that no-one wanted to touch have delivered an extended period of strong returns (because of the very volatility aversion that existed in the first place), perceptions of risk have begun to change. “Risk” ceases to mean short-term volatility, and gradually shifts to the risk of “missing out” on returns. As recent financial press articles illustrate, low but negatively correlated positive returns, once held up as being “outstanding”, quickly become “disappointing” and are compared with the higher returns on the very same traditional assets that investors did not want to be correlated with in the first place; capital preservation takes a back seat.

After years of warning about a low return world and the inherent risk of equities, the narrative has begun to change to one in which the gains we have seen in equity markets were “obvious” and that macro managers that have not ridden this wave have made some kind of catastrophic error. In our view, this marks only the early stages of a shift to a new “convention”. In the US it has been very costly to have avoided “risk” over the last five years: there have been very strong real returns from corporate bonds and equities, while cash has been negative and government bonds close to flat. Elevating a desire to “sleep well at night” as a priority, has been an expensive exercise from an opportunity cost perspective. Investors have seen the real value of their capital eroded, even if it has been in a low volatility fashion!

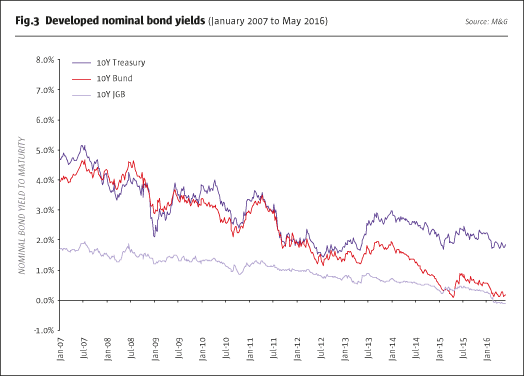

The “pain” of missing out is still in an early stage; investors we talk to still show deep interest in a strategy’s potential equity correlation but nothing like the same concern that it could be correlated with bonds. Moreover, in the UK and Europe it is also the case that the opportunity cost of avoiding volatility has yet to be felt to the same extent (except from real cash losses). However, with yields at their current levels, it seems like that pain is fast approaching.

Where does this transition leave macro strategies?

Some will legitimately note that the place of macro strategies in some portfolios may be as a supplement to exposure to traditional assets, and that looking for a lack of correlation over the long term is necessary to justify their inclusion. However, this doesn’t square with the argument that macro strategies have failed because they have not kept up with the equity rally.The reality is that the convention over what makes a successful macro strategy is already changing. Human beings can’t help themselves, they are attracted to things that have been working, and there is a collective psychology at work in the assessment of investment strategies just as there is for all boom and busts. The crowd agrees on a new convention − for example, the need for negative equity correlation is still trotted out in a knowing confident manner − becomes emotionally wedded to it, and only gives it up reluctantly after an extended period of repeated evidence that it is wrong.

Nor is it inappropriate that these changes should take place; any macro (or other absolute return) strategy that is worth its salt needs to be able to adapt to a changing environment. A time-varying and direction-varying exposure to a broad range of assets is critical. There should be no shame of being positively correlated to the best performing assets, so long as this is not a static feature of an approach.

Rather, macro strategies need to be prepared to identify those assets which are priced to deliver high or above average returns and avoid those which offer low or negative returns. This involves observing how valuations change over time, and how the “odds” are put in your favour when compensation for total risk, and not just short-term volatility, changes. Targeting the correlation with a single asset in this context is absurd.

We have just seen that regime changes don’t only take place in terms of investment opportunities but also in the demands of investors and what is perceived as a “good outcome” for macro strategies. To deal with this, macro funds need to be truly flexible and, importantly, cognisant that what investors want today may not be the same criteria on which they measure your performance tomorrow.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 124

The Wrong Type of Macro?

Macro’s failure to perform this year – why the bemoaning?

DAVE FISHWICK, M&G EPISODE

Originally published in the July 2017 issue