UBS Global Equity Long Short (GELS) UCITS returned 11.43% in 2013 and 9.18% in 2014 (net of all fees), with volatility of 4.3% leading to a Sharpe ratio north of 2.5. Consequently the composite earned The Hedge Fund Journal’s UCITS Hedge award for Best Performing Long/Short Equity – Global Fund over a two-year period, and is approaching its three-year milestone, having been seeded by UBS in August 2012. The vision of UBS Global Asset Management (UBS) was to create a daily dealing UCITS that fully exploited the expertise of the team, many of whom have worked in hedge funds or run 130/30 products before, but had no opportunity to demonstrate their shorting prowess at UBS until the UCITS was set up.

UBS is just starting to market the Irish-domiciled UCITS IV fund, which typically charges 1% management fees with 20% performance fees above a cash hurdle, floored at zero. This fund is quite separate from the UBS O’Connor multi-strategy UCITS that launched in 2015. UBS GELS’s return objectives – to deliver equity-like, high single-digit returns with lower volatility than long-only equities – have clearly been attained, and volatility is around 4% less than one-third of the MSCI World. Capacity for the product is estimated to be at least €1 billion, with the main constraint being availability of stock borrow for mid-cap shorts; the long book is much more scalable, but both long and short books have a wide investment universe, including mid-caps and emerging markets.

High-conviction investing

The long portfolio contains around 100 stocks and has a very high overlap with the managers’ long-only mandates at UBS, although position sizing – usually up to 3% – may well differ between the hedge fund and long-only mandates. Shorts, in contrast, have no overlap with the long-only portfolios, and this is easily achieved because UBS runs money in a relatively high-conviction way. No tracking error ceilings restrict the mandate to being “underweight” of a stock that the team do not like; they simply avoid it altogether. In a similar vein, all of the fund’s short positions are intended to generate absolute profits; they are not designed to just underperform longs, or be one side of a pair trade. Having 200 short positions allows for smaller position sizes, up to 2%, so that that stops are rarely hit and the team can take longer-term views.

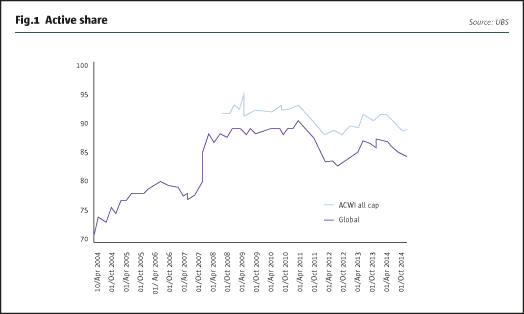

The “active share” for long-only mandates has increased since the global equity team was restructured in early 2008 (Nick Irish joined in March of that year and co-portfolio manager Charles Burbeck joined him in January 2013). It has ranged between 88% and 95% for global equity mandates (excluding emerging market (EM) and small cap) and has hovered around 85% for ACWI mandates (including EM and small cap), where active share was in the 70s in prior years (as shown in Fig.1).

Irish and Burbeck are the two managers who oversee six sleeves, run by six sector specialists for financials, consumer, tech and telecom, energy and utilities, healthcare, and industrials and materials. The two co-PMs decide on capital allocations to the six, determine the net long exposure and ratify all decisions. “A long-only business of $13-14 billion (in active global equity mandates) allows UBS to have a large, experienced team, including 40 regional analysts,” explains Irish, and incentives are well aligned with those of investors. “Most bonus compensation is deferred, of which a significant proportion is paid out as units in the GELS fund. This co-investment gives the entire team a keen interest in the success of the hedge fund,” Irish stresses.

Irish and Burbeck have known each other for 20 years and find the continuity of their working partnership is valuable. The duo met at Schroders, on the graduate scheme, and spent their first 10 years working at Schroders, before overlapping again at HSBC. The pair seem to have taken it in turns to be each other’s boss over the years. As soon as the opportunity arose, Irish brought Burbeck in to join him as co-PM of all strategies, making it the third time they have chosen to work side by side to re-create their previous success in generating top-quartile performance.

Intrinsic value investing

The co-PMs share a similar philosophy and process: “We are intrinsic value investors. Intrinsic value is the present value of the future cash flows of a business to which shareholders, as part-owners, have a claim,” pronounces Irish. The pair also think markets can be inefficient, and so want to buy at a discount to intrinsic value. If they had to be pigeonholed into a box, it would be core value, and they always need to be able to make a valuation case for longs, and shorts must always be overvalued. Quantitative screening of thousands of companies whittles the universe down to shortlists of potentially overvalued and undervalued companies; but valuation alone is not enough.

The life cycle of a business is useful in informing the process, and UBS has often found markets can become too pessimistic or over-optimistic. Among many overseas visits was a trip to Spain, with the specialist global consumer analyst, which convinced them that there was value in selected broadcasters. Granted, advertising revenues had halved and the industry had consolidated from seven to two players. But valuations were, according to UBS, extrapolating a continuing contraction, whereas UBS saw the downturn as cyclical. When UBS noticed that the Spanish economy was starting to recover, and the two remaining players now enjoyed enhanced pricing power, they formed a view that depressed profits might double year on year. The relatively stable fixed costs of the Spanish operators strengthened the case.

If markets can be over-pessimistic about cyclically challenged companies, they can also be premature in calling the peak of a growth story. Dynamic discount apparel retailer Primark is owned by Associated British Foods, and UBS reckons “the market assumes that returns fall back to the cost of capital,” but they beg to differ. The managers think that the growth momentum can continue. In contrast to a series of UK retailers that have struggled in Europe, ABF has done well in Germany and Spain and may also be rewarded for its first step into the US.

“A value bias does not prevent us from owning technology,” says Burbeck. The largest net sector long for the fund today is technology, which has also been a source of shorting opportunities. A richly valued social media stock was shorted on concerns that it had limited ability to monetise its customer base, while Facebook has been a profitable long position because it has been successful at monetising the transition from desktop to mobile usage. Google is also a core long, as UBS thinks the shift from print to online has further to run, and YouTube could be significant as advertising spending moves from TV to online. “This transition is at a much earlier stage than that from print, and analyst Richard Green thinks that as the world’s biggest broadcaster, YouTube has huge potential,”explains Burbeck. Apple is another technology holding where UBS are bullish. If the stock may be popular amongst hedge funds, it remains a structural underweight for the long-only community.

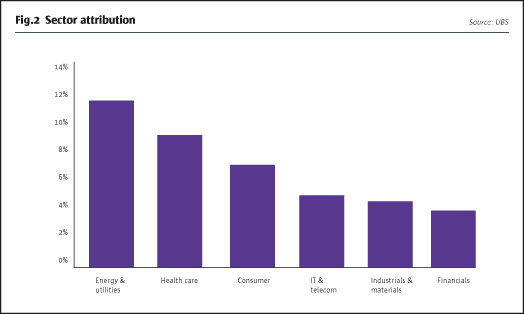

If technology is the largest net long sector, in early 2015 energy was also the largest gross exposure, at 31%, as Irish and Burbeck have a high degree of confidence in the opportunity set. Sector attribution (shown in Fig.2 from inception in August 2012 to February 2015) illustrates how the energy sector has made the largest contribution.

A slightly net short stance in energy may have helped in 2014, but on average the fund has been broadly neutral, and 2013 was also a strong year. The team’s specialist global energy analyst, Ellis Eckland, makes no claim to have foreseen the halving of the oil price, but quotes Warren Buffett that “When the tide goes out you see who is swimming naked.” On the short side Eckland has profited from shorting stocks with unproven management that have a poor track record of creating value for shareholders, including exploration companies that have a habit of hitting dry wells.

In his long book, Eckland offers a non-consensus perspective on the Canadian oil sands producers. He thinks they are lower cost than commonly perceived, for both cyclical and structural reasons. Cyclically, he cites “the rapid drop in the Canadian dollar (down 16% in the last seven months) and falling costs in the Fort McMurray region,” while structurally, he argues, “the total cost structure to sustain production is actually lower than that of most of the integrated major oil companies,” because oil sands are so long-lived, whereas the oil majors, exposed to projects with declining output, will be forced to escalate capital spending merely to maintain flat production. If operating costs in oil sands at $40 may be double the $20 seen elsewhere, then sustaining capital costs as low as $6 could be well below the $30 or more that may be needed to maintain output in other oilfields.

In healthcare, the second largest contributor, performance has come from longs, including Abbvie, HCA, and Shire Pharmaceuticals. Irish expects further consolidation, but the fund’s picks are not solely predicated on corporate activity. The fund owned Shire before and after the abortive takeover, and is now pleased to see the stock back to the highs where it was a bid target.

In terms of geographic weightings, an underweight in the US has hindered performance, while an overweight stance in Japan has been a positive contributor to performance, particularly as the weaker yen helps exporters. Holdings have included Subaru car-maker Fuji Heavy Industries, which has benefited from its strong model line-up in the US car market.

Tactical beta

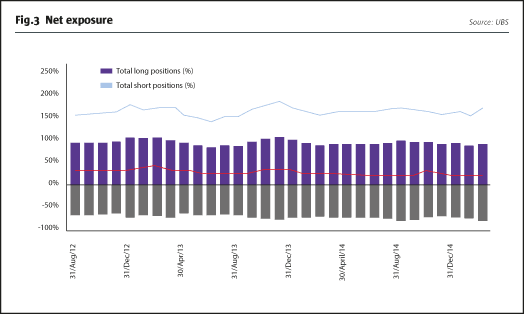

On top of long alpha and short alpha, UBS aims to add value by tactically adjusting the net exposure, which has so far ranged from 12% to 40% (see Fig.3).

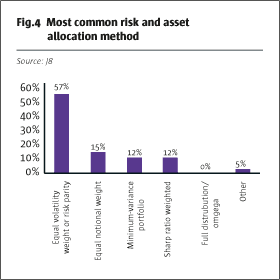

The net exposure decision is informed by a number of inputs, including a multi-factor model that uses seven indicators (shown in the pie chart, Fig.4) to help determine the net long exposure, as well as two proprietary UBS valuation methodologies: GEVS (Global Equity Valuation System), used since the 1990s, and Valmod, used since the 1980s. The net is typically between 20-40%, but could range from 0% to 75% in raw terms, and the fund could go net short in beta-adjusted terms.

Risk management

All of this fundamental stock-picking sits inside a rigorous risk framework. Burbeck emphasises the importance given to portfolio construction and risk management at UBS, and he questions whether some hedge fund launches are paying enough attention to risk. The GELS fund’s largest peak-to-trough drawdown, using daily data, has been just 2.89%, and an extensive list of tightly defined risk controls keeps everyone on their toes. “Review triggers” are reasons for a formal review, which will occur simply if the fund is down 1% over a month, or if any individual position has lost 15% in absolute terms over one, three, six or 12 months. “Action triggers”, in contrast, are in effect hard stops that force the fund to cut or eliminate positions. A 3% monthly loss for the fund will require its net long to be scaled back. Shorts that have grown to 3% (from an initial size of no more than 2%) are cut or removed, as are longs that have lost 30% or more over one, three, six or 12 months. Irish and Burbeck have the power to implement the triggers, and their dedicated portfolio construction and risk analyst, Dan Slome, can also instruct dealers to execute trades.

Yet despite these constraints, portfolio turnover is remarkably low for a hedge fund because diversification (and sound investment decisions) have meant that the triggers are seldom touched. Average holding periods are two years for the long-only and likely to be similar on the hedge fund, because, as Burbeck observes, “the one certainty is dealing costs.”

As well as strong risk controls, compliance is integral to the investment process. Running a hedge fund parallel to long-only money caused problems for UK insurer Aviva, which was recently found to have inappropriately allocated trades amongst accounts. “Systems in place would make that very difficult here unless somebody was doing it fraudulently,” says Irish. UBS run a total of over $200 billion in equities, and are nearly always doing trades across multiple accounts, so algorithms allocate the trades rateably over the accounts, and compliance procedures ensure that all clients are treated equally.

In its first two and a half years, UBS GELS has annualised at double-digit returns, with much lower volatility than many funds. Broad-based performance attribution has seen all six sector sleeves make positive contributions. The process is scalable and there is plenty of capacity available for external investors to allocate alongside the team’s own holdings in the fund.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical