The euro-zone economies are doing a little better in the eyes of the European Central Bank (ECB) while the UK economy is being slowly dragged lower by increasing Brexit fears in the aftermath of a surprising June parliamentary election. And, on the global scene, the pullback of the United States from its leadership position on trade and regulatory deals may well complicate the Brexit negotiations as the European Union (EU) is emboldened to assert itself more aggressively on the world stage, making Brexit a pawn in a much larger game. We will start with a quick review of the UK election’s implications for Brexit negotiations, move on to the economic analysis of the EU and UK, and close with some perspectives on how developments inthe global trade and regulatory scene might impact everything from Brexit to job creation in the United States to global growth.

State of Brexit negotiations post-UK election

Brexit negotiations have become more complicated. The best cards are now mostly in the hands of the EU. And, neither strategy – a “Hard Brexit” or “No Deal” – are viable negotiating options for the UK. As the olde English proverb goes: “There’s many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip.” When Prime Minister Theresa May called the snap election for June 8, 2017, the Conservative Party held a 20%-plus lead in the opinion polls. She expected to gain more seats in parliament and win a bigger majority while earning a five-year term carrying her government well past the two-year Brexit negotiations that end in 2019. The voters did not cooperate. The Labour Party gained a net 32 seats, winning in districts formerly held by Conservatives, the Scottish National Party (SNP), and the UK Independence Party (UKIP), ending up with 262 seats. The Conservatives lost 13 seats and now have only 318 seats, just short of an outright majority. Post-election, the Conservatives reached out to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland and their 10 seats to allow them to govern. Moreover, the Scottish Conservatives picked up 12 seats and plan to vote as a bloc on critical issues to Scotland, such as Brexit.

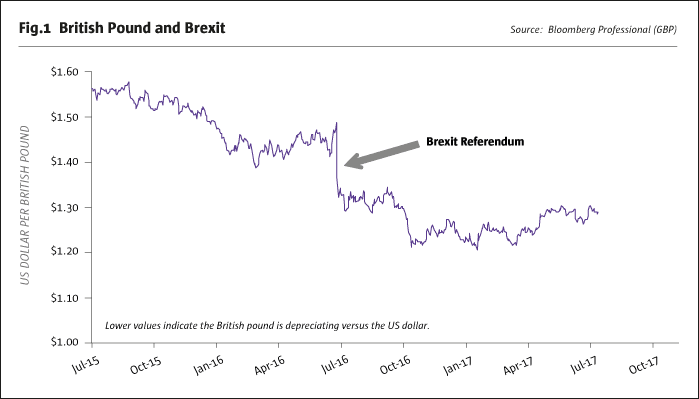

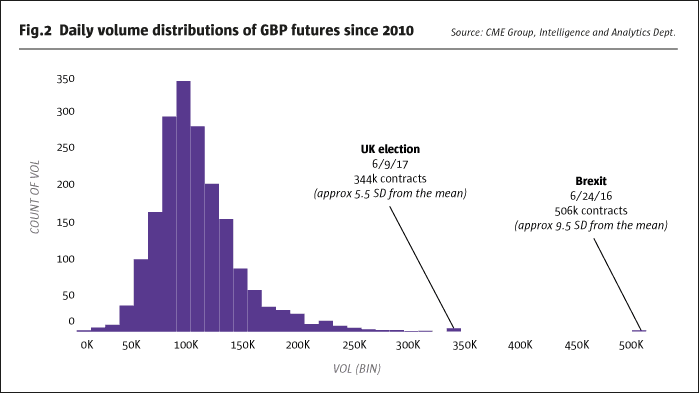

The election outcome puts tremendous power into the hands of two small groups in Parliament at Westminster. Either the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) or the Scottish Conservatives can bring down the government of Theresa May at will. Since the Conservative-DUP alliance is not likely to be strong, stable or durable, and the Scottish Conservatives have a very different social agenda from the Northern Irish, the probabilities suggest another election or another Prime Minister could be on the cards. With all due respect to the Queen and Prime Minister, the two most important leaders in determining if/when there will be another election are Arlene Foster of Northern Ireland and Ruth Elizabeth Davidson of Scotland. During the election campaign, the Conservatives emphasised “strong and stable” leadership in the person of May and rarely discussed Brexit. The Labour Party campaigned on more money for health, education and the police, all to be paid for by higher taxes on upper-income Britons. The election was not fought about Brexit strategies. Indeed, the anti-EU party, UKIP, was wiped out, with Conservatives taking some of those seats and Labour the others. That is, UKIP, having won the Brexit referendum back in June 2016, went back to being split on other issues. The election was much more about the age gap – younger voters for Labour, older voters for the Conservatives— about austerity versus more social programs, and, with the tragic terrorist violence in Manchester and London, the election also turned on domestic security. So, while the election was not fought on Brexit, the outcome will hugely impact Brexit, and the type of exit will set the tone for the British pound.

Brexit was always going to be complex, and now it will be much harder for the UK to cut a deal that will resonate with its own voters, making the outcome of the next parliamentary election even more uncertain, whenever that election might come. For now, the Democratic Unionist Party will be demanding that the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland be kept open, and goods and services be allowed to flow freely. This demand implies that the concept of a hard Brexit – May’s former position – is now out of the question for this coalition government to pursue. While we note that a soft Brexit deal would be more favorable for the British pound than a hard Brexit, it is not clear if any deal is possible that will pass muster in the currently divided UK parliament. And, with two strong leaders on the EU side – Angela Merkel in Germany and France’s Emmanuel Macron – the EU is not likely to allow the UK to keep trade and customs union benefits without a high price being paid, even if many in the EU are friendly to a soft Brexit arrangement. Put another way, the Brexit negotiations are not at all likely to be settled cleanly or quickly. And, if negotiations are delayed and/or bog down, and if the pendulum swings toward a no-deal or a bad-deal, the pound is likely to come under downward pressure.

The uncertain outcome and high probability of long delays in a Brexit deal leaves the UK financial sector in a bind. Financial companies with strong Euro-swap or European client business, including asset managers, may face strong EU regulatory pressure to conduct and book certain Euro-related business within the EU. The EU will be arguing that Euro-denominated swaps will need to be cleared inside the EU, so that the ECB will be the primary backstop if there was a crisis, instead of leaving it to the Bank of England to take care of Euro-denominated swaps business. The implication is that a financial company will not be able to wait until the Brexit negotiations are complete to hedge their business risks. Some jobs are going to leave London in 2017-2018 for the EU, and London’s ability to attract new jobs will be minimal – even assuming London retains its status as the top financial center in the UK/EU time zone. And, with London’s financial sector unsettled, UK companies with exports to the EU will also probably be extremely cautious in terms of any expansion plans. In short, there is more confusion and uncertainty on the way. And if a new election is called in the UK, there are no guarantees that it won’t be another hung parliament. Moreover, whichever party or leader negotiates Brexit is unlikely to win any popularity contests given the deep divisions even among Brexit supporters. The UK economy is not likely to take all this ambiguity well. Slower growth in the second half of 2017 and into 2018 is likely. All parts of the country may see significantly less investment as Brexit anxieties rise with uncertainties about leadership at Westminster. London’s economy will feel a distinct chill.

EU & ECB economic prospects

The European Central Bank (ECB) is getting more optimistic about the prospects for a modest, sustainable economic expansion, say 1.5% to 2% real GDP annually, or about the same as the United States and a little bit more than Japan. The overall EU inflation rate is not moving higher, however, so the ECB may talk about scaling back asset purchases some time down the road; the focus of the ECB is more likely to exit negative ECB deposit rates as soon as possible in the second half of 2017. Yields on the 10-year German Bund have already risen to reflect the shift in ECB policy intentions and the euro has rallied against the US dollar in 2017 even as the Federal Reserve has raised rates and contemplates shrinking its balance sheet.

We note that there is some complacency within the EU as to what Brexit will mean for the bloc’s economy. The general view inside the EU is that it holds all the cards in the negotiations, so it will just wait the UK out. To the extent that the UK views “no deal” as worse than a “bad deal,” the EU negotiating position will likely be successful even if it takes a year or more past the 2019 deadline to complete a deal. The UK may feel time pressure, but the EU may not. If the UK wants to retain access to the customs union, there will be a steep price to be paid, which will ease some of the immediate budget issues for the European Commission in Brussels. In short, the current prevailing view is that the EU economy will not be hurt much by Brexit.

An emboldened EU: global trade deals without the United States

The story gets more complicated. There are interesting implications for the Brexit negotiations and for the euro-zone economies from the US withdrawing from world leadership on trade and regulatory policy. The EU is likely to be emboldened to take a much more aggressive posture in seeking bilateral and multi-lateral deals on trade and regulatory issues, with or without the participation of the US and Brexit-frozen UK. That is, there is a real desire by the EU, Japan and China to push forward with their own deals, with the lack of a US presence simply being the new reality. We are seeing an EU-Japan deal go forward, and a new Trans-Asia deal without the US is entirely possible. China, especially, will be moving to cement its place as a world leader in trade deals and to gain influence in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. And on the regulatory side, the EU has already warned the US about rolling back certain provisions of the Dodd-Frank financial regulations that the EU views as essential to global regulatory coordination.

As Nobel Laureate Professor Milton Friedman once pointed out: “The most important single central fact about a free market is that no exchange [or trade deal] takes place unless both parties benefit” [or at least perceive they will both benefit]. Thus, as the major economies of the world seek to ink trade deals without US participation, the United States will face tougher export competition, and a slower than otherwise long-term economic growth path. In this world scenario, US companies will have strong incentives to expand their businesses inside the new trade zones and outside the US. The bottom line is that we are entering phase in which EU will increasingly prioritise pushing its own vision of trade and regulatory policy on the world stage, marginalising the US and UK while allowing Brexit negotiations to be a secondary priority.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 124

UK Economy to Feel the Heat of a Complicated Brexit

Uncertainty and delays

BLU PUTNAM, CHIEF ECONOMIST AND MANAGING DIRECTOR, CME GROUP

Originally published in the July 2017 issue