The rate-rise debate is in full swing at the Federal Reserve (Fed). The end of quantitative easing (QE) in late 2014 brings a new era to monetary policy-making in the US. There is no going back to the mindset of the Fed prior to the financial panic of 2008, because, paraphrasing John Maynard Keynes, “when the facts change, I change my mind”.

And the context of monetary policy-making has changed, dramatically. The Fed now has a balance sheet of over $4 trillion, or 25% of GDP, compared to the pre-crisis level of 6%. This swollen balance sheet comes with $2 trillion of excess reserves not needed to meet banking regulatory requirements. This massive over-supply of federal funds means that the traditional operational tools of the Fed to fine-tune short-term interest rate policy, such as repurchase activities, are no longer remotely up to the job.

The US economy is not the same either, due to secular shifts of tectonic proportions. The labour force is ageing, reinforcing a 15-year trend toward lower labour force participation rates. State and local governments, as well as the US Postal Service, have dramatically downsized to align better with their budget realities. The nearly one million government jobs lost between mid-2009 and mid-2013 explain better than any other one fact why QE did not work to encourage more rapid job growth even as the private sector recovered reasonably well. QE was never going to save a single job in state and local governments coping with lower revenues. Moreover, retail businesses are faced with the challenges and opportunities of e-commerce. As main street retailers expand e-commerce web sites, they are also resorting to more part-time workers in their stores, helping explain the elevated number of part-time workers. And then there are the controversies around how the Fed communicates its policy-making forward guidance. The Bernanke-Fed’s use of calendar-based guidance was effectively dead on arrival, since everyone knew what Keynes knew – if the economic data shifted, so would policy. Then the Bernanke-Fed tried indicator guidance for labour markets and for inflation. Again, the single-number unemployment guidance was a failure from the start. It was not a trigger, just one milestone among many to be met, and required more explanation rather than providing clarity. Under chairwoman Yellen, the Fed quickly abandoned specific targets and communicated a more holistic and robust approach to interpreting a wide variety of economic data. And the failed experiments with forward guidance and expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet have energized a set of mostly conservative politicians to revive the debate over whether the Fed should adopt a more rules-based approach to policy-making, restricting discretion.

The next Fed rate decision

Most market analysts are focused on the degree of improvement in the economy and specifically in the labour markets as the key to the timing of when the Fed will take its first step to move away from the zero-rate policies enacted in the fall of 2008. Labour market trends – a low rate of weekly new unemployment claims, a healthy rate of monthly job creation, and a downward trend in the unemployment rate – all point to a Fed decision to raise its target federal funds rate range to 0.25%–0.50% some time in 2015. There is, however, another perspective on why the rate-rise decision is likely to come in 2015, and possibly a few Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings sooner than the consensus view.

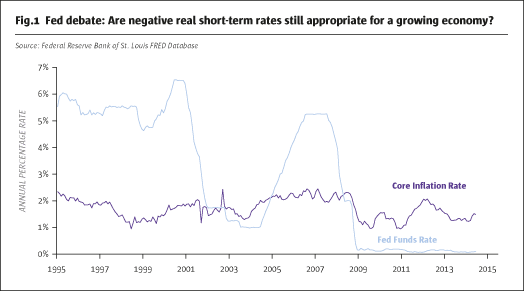

Many Fed board members and regional Fed Presidents are likely to see the end of QE as the time to redefine monetary policy decision-making and to rethink various issues from forward guidance, size of the balance sheet, to how to implement policy decisions, etc. The key overriding question from this perspective on the future role of monetary policy is simply: “Are emergency measures, such as QE and negative real short-term rates, that is short-term rates held at zero and below the prevailing rate of inflation, actually appropriate for an economy that has reeled off five years of modest economic expansion in the face of fiscal tightening and severe international headwinds?” As this debate unfolds, with its many smaller themes and byways, we expect more and more FOMC members to take a position that the sooner emergency measures are ended, the better. QE is already on track to end in late 2014. The zero short-term rate policy may be next to go.

The possible new role of interest

Regardless of the motivation, once a decision is reached to raise the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points from the current range of 0.00%-0.25% to 0.25%-0.50%, the question is how to implement and enforce the new policy. In the old, pre-crisis days, the Fed would use reverse repurchase operations to drain reserves and nudge the effective federal funds rate higher. Back in 2007, a $500 million repo operation would have impacted the equivalent of 30% of excess reserves. In the new world of a bloated Fed balance sheet, even a $5 billion repo operation would only impact 0.02% of excess reserves – hardly likely to move markets. The new tool of choice to enforce short-term rate policy is likely to be the rates the Fed pays on excess and required reserves, both set at 0.25% for the post-crisis period.

The first thing to appreciate is that only the Fed can destroy or create federal funds – which are defined as deposits held at the Fed by the banking system and certain other agencies and entities. If the Fed buys US Treasuries, they create federal funds to pay for them. If the Fed sells US Treasuries, not that it will, federal funds would be destroyed when the Fed is paid back. All the banking system can do is move federal funds among themselves. The key is what value the Fed places on federal funds, and the upper end is likely to be defined by the rate paid on excess reserves. If the Fed raises to 0.50% the rate paid on excess reserve deposits at the Fed, then should any institution need federal funds they would have to accept a lower interest rate. The current discount is about 17 basis points, so a rate of 0.50% on excess reserves would imply a 0.33% federal funds rate, more or less.

If the Fed decided to be fancy, it could set the rate paid on required reserves at 0.25% to set the floor. This might work, given that the main reason a bank would want to bid for federal funds is that it was short of required reserves. With $2 trillion of excess reserves, though, few banks come up short any more.

Corollary decisions to shrink balance sheet

The long-term solution for the Fed is to work toward reducing its balance sheet. Outright sales of assets have been ruled out, mainly because no one wants to disturb the mortgage market by sales of MBS or by potentially pushing up bond yields with Treasury security sales. The Fed, however, can make a decision not to reinvest coupons or principal repayments. While a decision not to reinvest interest and principal is not going to shrink the balance sheet quickly, as the Chinese proverb suggests, a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. With a growing desire to unwind the emergency policies of the QE era, there is a possibility that the FOMC could decide to stop reinvesting interest and principal as early as the December 2014 or January 2015 meetings.

Message matters more than method

The main challenge of forward guidance is the signal it sends to consumers and businesses, as opposed to the actual mechanics of providing the message. Unless legislation is passed in the US Congress, which is a total non-starter, to require a rules-based approach to interest rate policy, the Fed is going to retain its discretion. And discretion means always emphasizing the caveat that if the economy changes direction, so will policy.

Our perspective is that what really matters is the message. When the Fed tells the world it plans on keeping emergency policies in place, such as zero short-term rates implying negative inflation-adjusted rates, then the message is that the Fed thinks the economy is exceptionally fragile and could collapse at any time. This is a very negative message, especially in light of the fact that the economy has been posting steady, if not exciting, real GDP growth for five years straight. Put another way, there may be considerable debate and discussion around the appropriate manner to provide guidance concerning how the Fed will make its decisions, but in the current context, it is getting harder and harder to justify a message that the economy is fragile and could easily collapse.

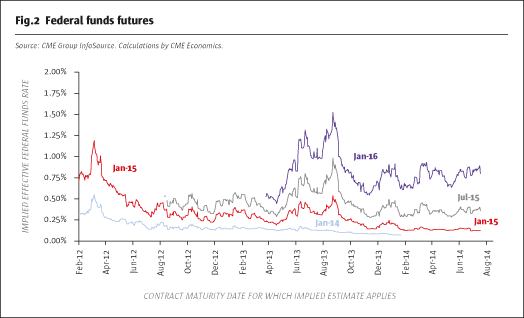

It is key to note that removing emergency measures does not mean the Fed has to move to a tight policy. The Fed can easily accommodate chairwoman Yellen’s view that slack remains in labour markets, since short-term rates more or less in line with the prevailing rate of core inflation would still be deemed accommodative by any standard of measuring monetary policy. As we write, the markets seem to agree, since mid-year 2015 federal funds futures are trading around a price of 99.65 to 99.70, which implies a mid-year federal funds rate of 0.30% to 0.35%. Which corresponds with the timing probabilities in CME Group’s Fed Watch Tool (www.cmegroup.com/fedwatch). This is exactly where federal funds might trade if our analysis of the implications of a 0.50% rate paid on excess reserves is correct.

Bluford (Blu) Putnam has served as managing director and chief economist of CME Group since May 2011.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 98

Understanding the Rate-Rise Debate

US monetary policy in the aftermath of Quantitative Easing

BLUFORD PUTNAM, CHIEF ECONOMIST, CME GROUP

Originally published in the October 2014 issue