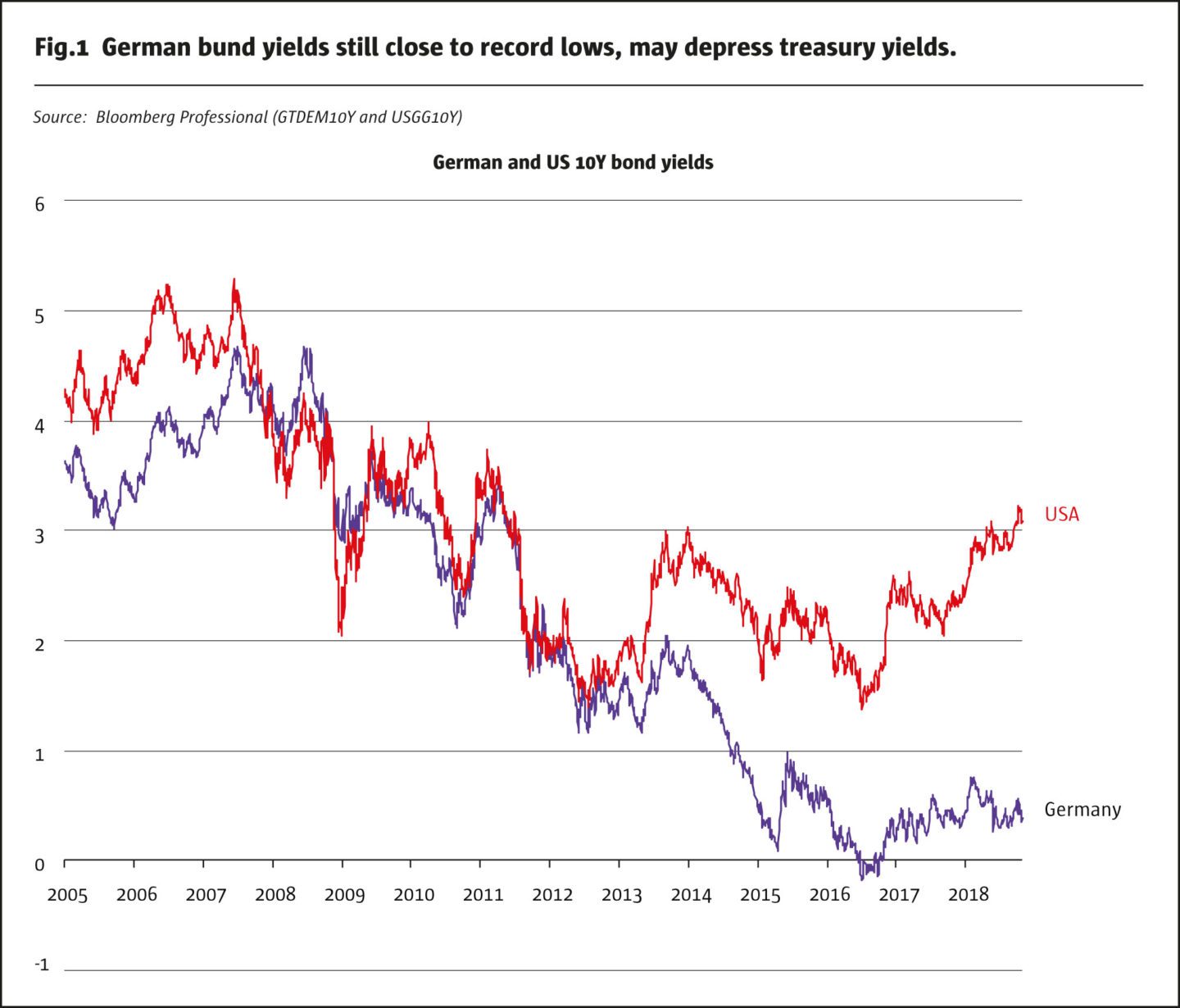

Is a significant change on the way in German fiscal policy? The markets don’t think so. The 10Y German Bund yield is still close to historic lows with a yield of 0.40%, showing little reaction to Bavaria’s recent elections in Bavaria, Hesse or news that Chancellor Angela Merkel is stepping down as head of the Christian Democrats (CDU). But change may be on the way. One that would be bearish not just for German bunds but for highly rated government bonds globally, including US Treasuries. (Fig.1).

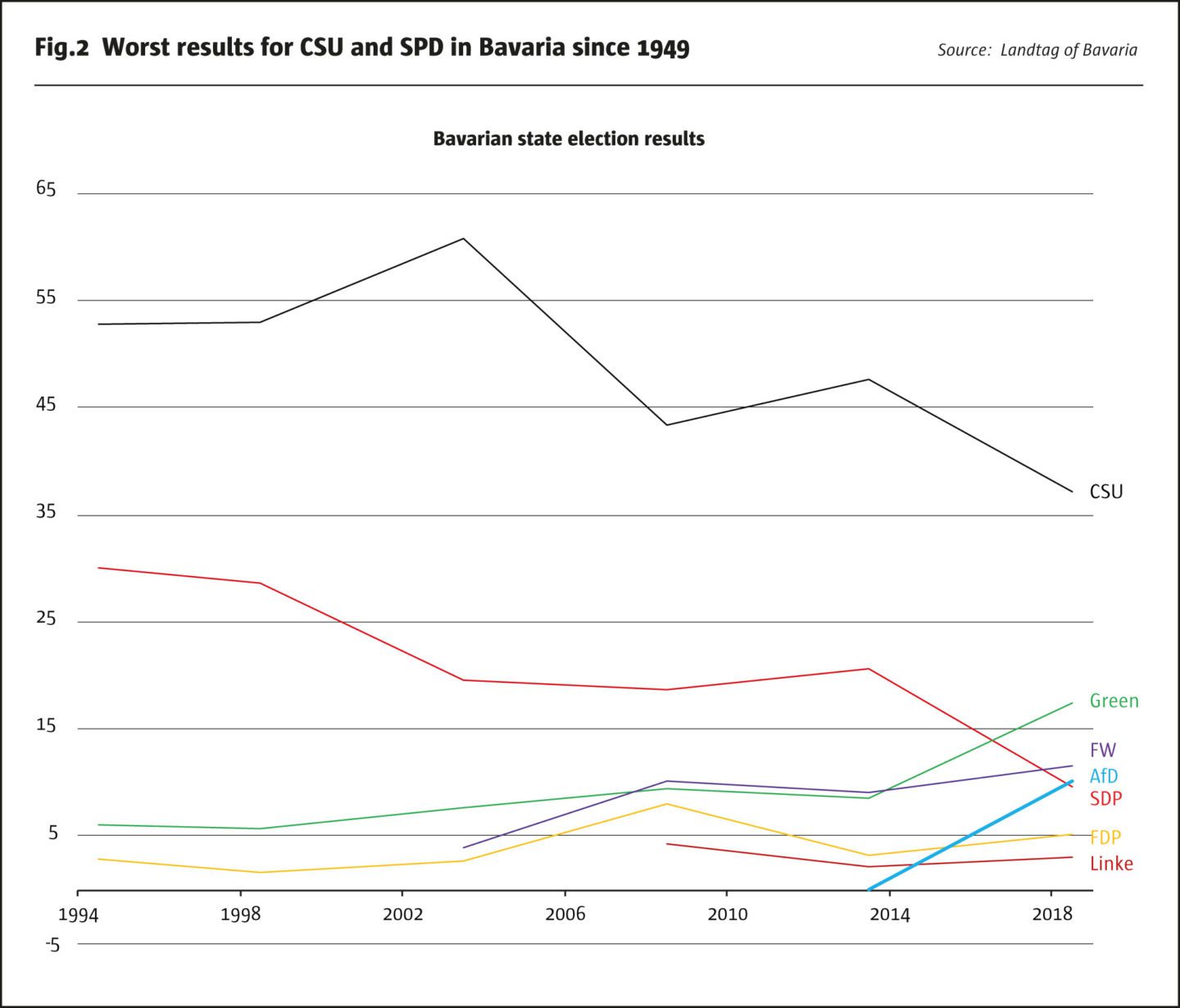

The reason: Merkel’s seemingly unsinkable political ship is taking on water. For the past 13 years, she has been the de facto leader of Europe and has imposed economic austerity at home and in Europe. But her fortunes are turning, and not for the better. On October 14, her Christian Democratic Union’s sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), was routed in Bavaria, Germany’s second most populous Lander (state), delivering the worst election result since 1949. Moreover, the fortunes of her junior coalition partner, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) also sank to post-war lows, finishing in fourth place with less than 10% of the vote (Fig.2).

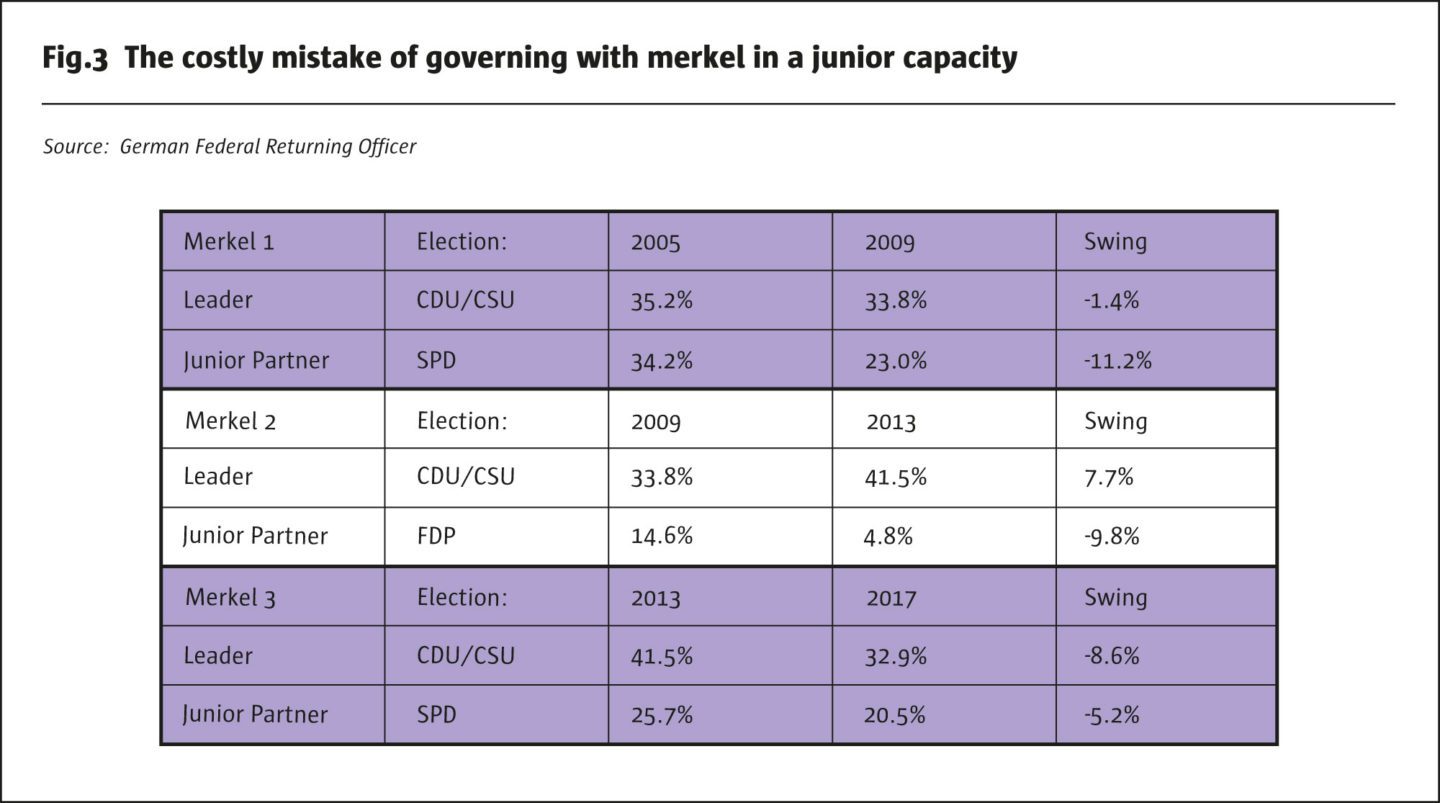

Even before the election result in Bavaria, Merkel was under intense political pressure. In the 2017 election, her party’s share of the vote fell from 41.5% to 32.9% following her decision to admit one million refugees without consulting Parliament. In the previous two elections, her CDU/CSU coalition survived at the expense of its junior coalition partners. In her first term, she governed with the center-left SPD. In 2009, after their fortunes waned, she governed with the pro-business Free Democratic Party (FDP). In 2013, the FDP failed to clear the 5% threshold to win seats in the Bundestag, so she flipped back to the SDP, which suffered another stinging defeat in 2017 (Fig.3).

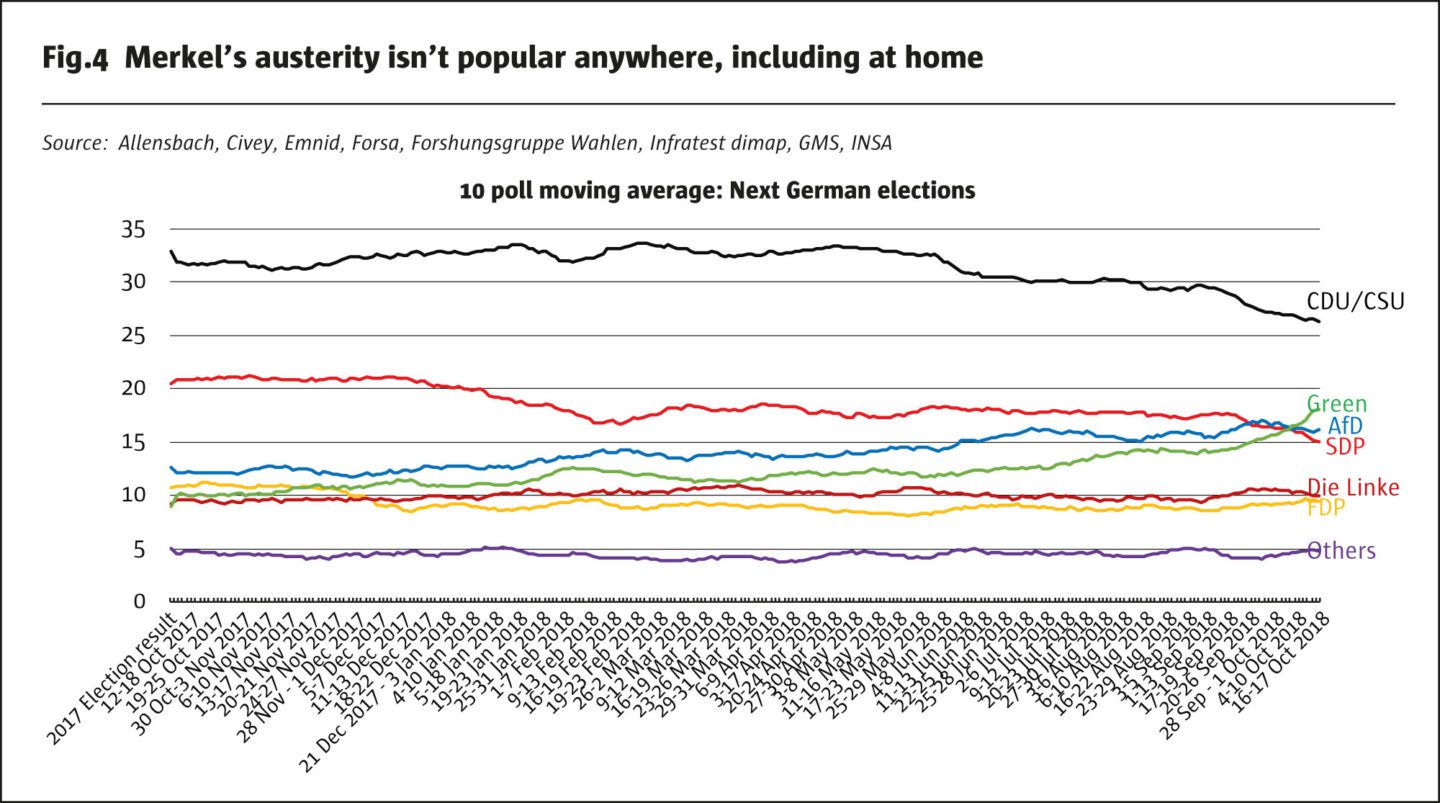

Only after months of negotiations did the SPD agree to a third pact, becoming Merkel’s junior coalition partner once again. National polling confirms that the Bavarian results were no fluke. Merkel’s party, the CDU/CSU, is polling around 26% – a postwar low. The SPD has slipped into fourth place, narrowly behind the nationalist Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) and the Greens (Fig.4). Her own party may soon seek to replace her as leader.

The problem for any potential replacement for Merkel is that Germany needs more than a new face or leadership. It needs new policies – and not just on immigration. As controversial as immigration may be, Germans would probably be much more accepting of immigrants if they felt economically secure. While Germany’s unemployment rate has fallen to record lows, wages remain stagnant, with many newly employed workers struggling in low-paying jobs.

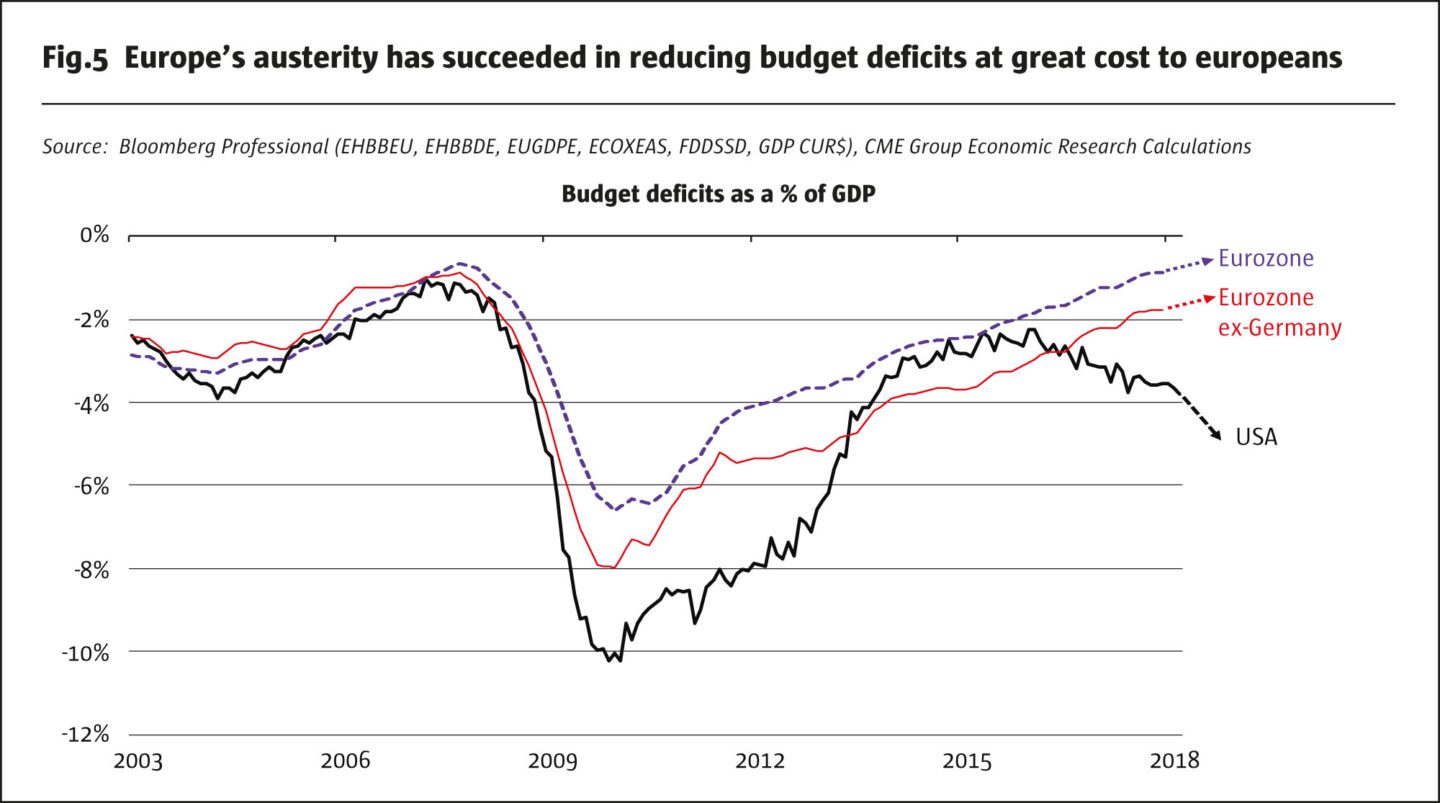

Merkel’s modus operandi has been to reduce fiscal deficits, both at home and abroad. From 2009 to 2012, it produced disastrous results in Southern Europe, with tax hikes and spending reductions in Greece, Portugal and Spain leading to economic depressions. Only after she agreed to hand the keys over to European Central Bank (ECB) President, Mario Draghi, and his ultra-easy monetary policy at the ECB, did the rest of Europe begin recovering.

Since then, budget deficits have fallen across the continent (Fig.5), while the ECB shouldered the task of supporting the economic recovery. In some ways Merkel’s insistence on fiscal austerity has been a success. The problem is that it has been extremely unpopular politically, at home and abroad. Center-left and center-right parties have collapsed in Greece, Italy and Spain, giving way to more fractured and extreme politics – a phenomenon on the rise in Germany, too. Watching the economic plight of the Greeks, Portuguese and Spaniards and the poor response of European authorities may have tipped voters in the UK to narrowly endorse Brexit in 2016. While Brexit has its own set of potential consequences for markets, especially for the British pound, what follows Merkel could have much bigger consequences for bond investors globally.

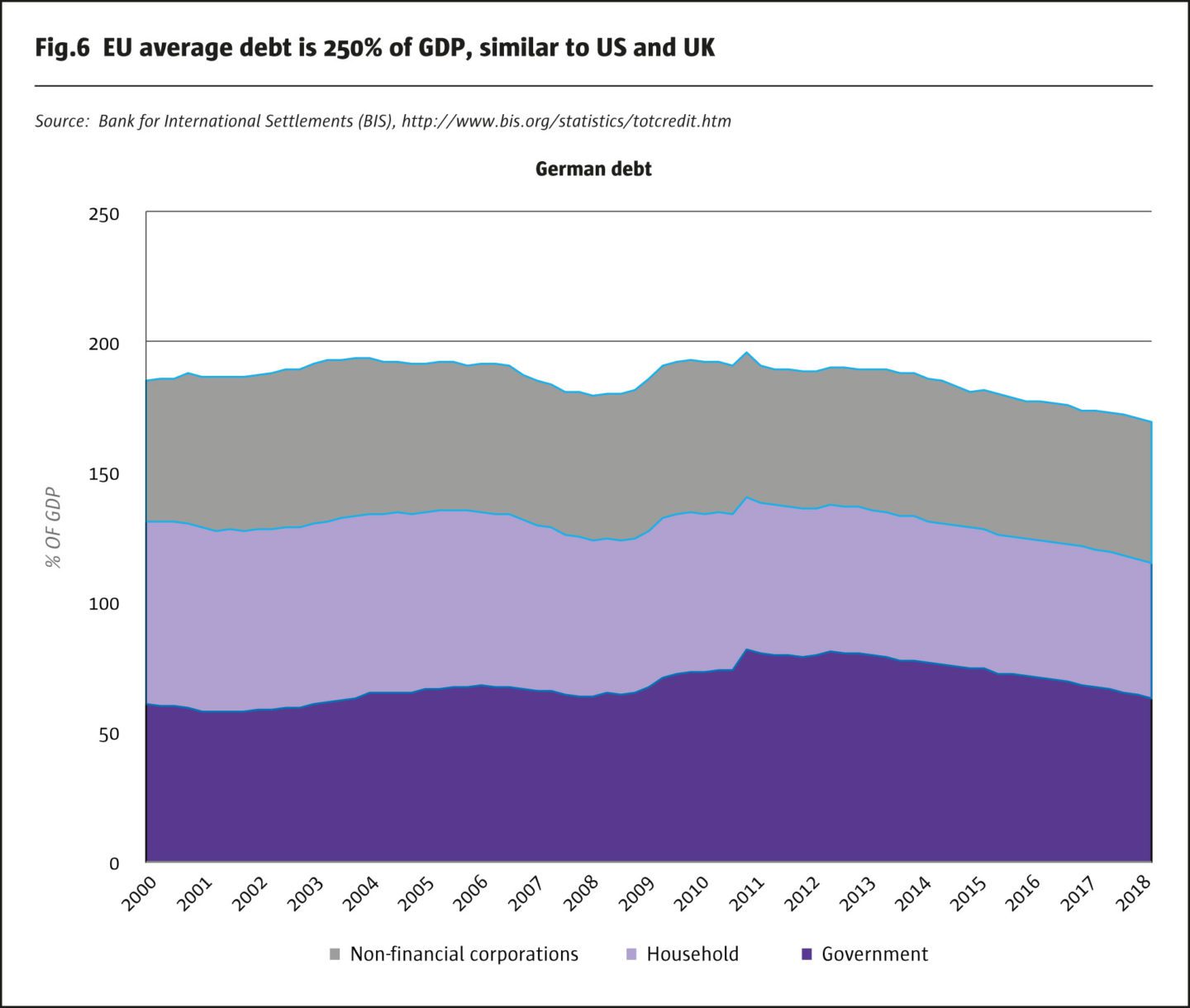

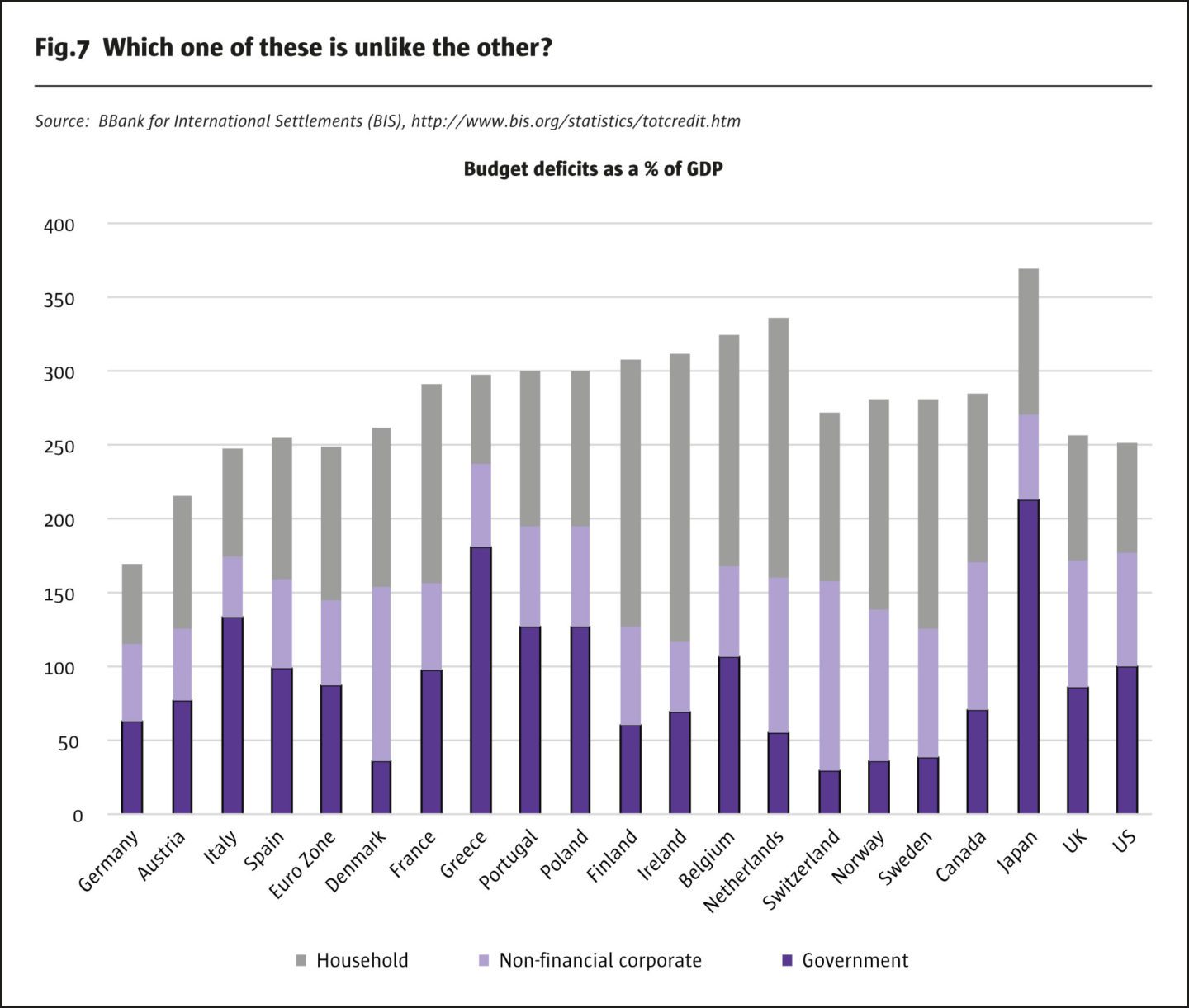

Merkel will hand any successor one amazing gift that might boost the fortunes of both the governing CDU/CSU/SDP coalition and Germans/Europeans in general: an enormous budget surplus. Germany’s 1.3%-of-GDP surplus when combined with 4% nominal GDP growth has sent Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio plunging by about 5% per year. By the end of 2018 public debt should be less than 60% of GDP – one of the Maastricht Treaty’s criteria for euro membership that incidentally no other country in Europe meets. Most other nations have public-debt ratios of close to 100% of GDP, with the worst offenders, Italy and Greece, at 135% and 175%, respectively.

Moreover, Germany has relatively low levels of corporate and household debt as well. Total debt for the public and private sector was around 167% of GDP and falling at the end of Q1 2018 (Fig.6). On average, developed countries have debt levels closer to 250% of GDP (Fig.7).

Whether to bolster their own electoral fortunes or to altruistically make Germans better off, whoever might replace Merkel will be sorely tempted to enact a vast fiscal expansion. In some ways Merkel’s crusade against debt has been laudable. She hands her successor a clean balance sheet. That said, if investors are willing to lend Germany money at 0.4% for 10 years and at 1.0% for 30 years, why not borrow it and invest in infrastructure or growth promoting tax cuts?

Germany’s roads, bridges and tunnels are in need of improvement. The country has the fiscal resources to expand high-speed rail lines. At 30%, corporate taxes are abnormally high compared to a global average closer to 20%. A corporate tax cut could be in order. If Germany wants to make Frankfurt a post-Brexit alternative to London for financial services, cutting the 45% top tax rate on income could make Germany a more attractive candidate. Lower income and corporate taxes might also give Berlin a fighting chance of becoming the European technology hub and alternative to Silicon Valley that it aspires to be. Middle-class tax cuts on the lower 14% and 24% tax brackets could also boost confidence and the popularity of the governing coalition.

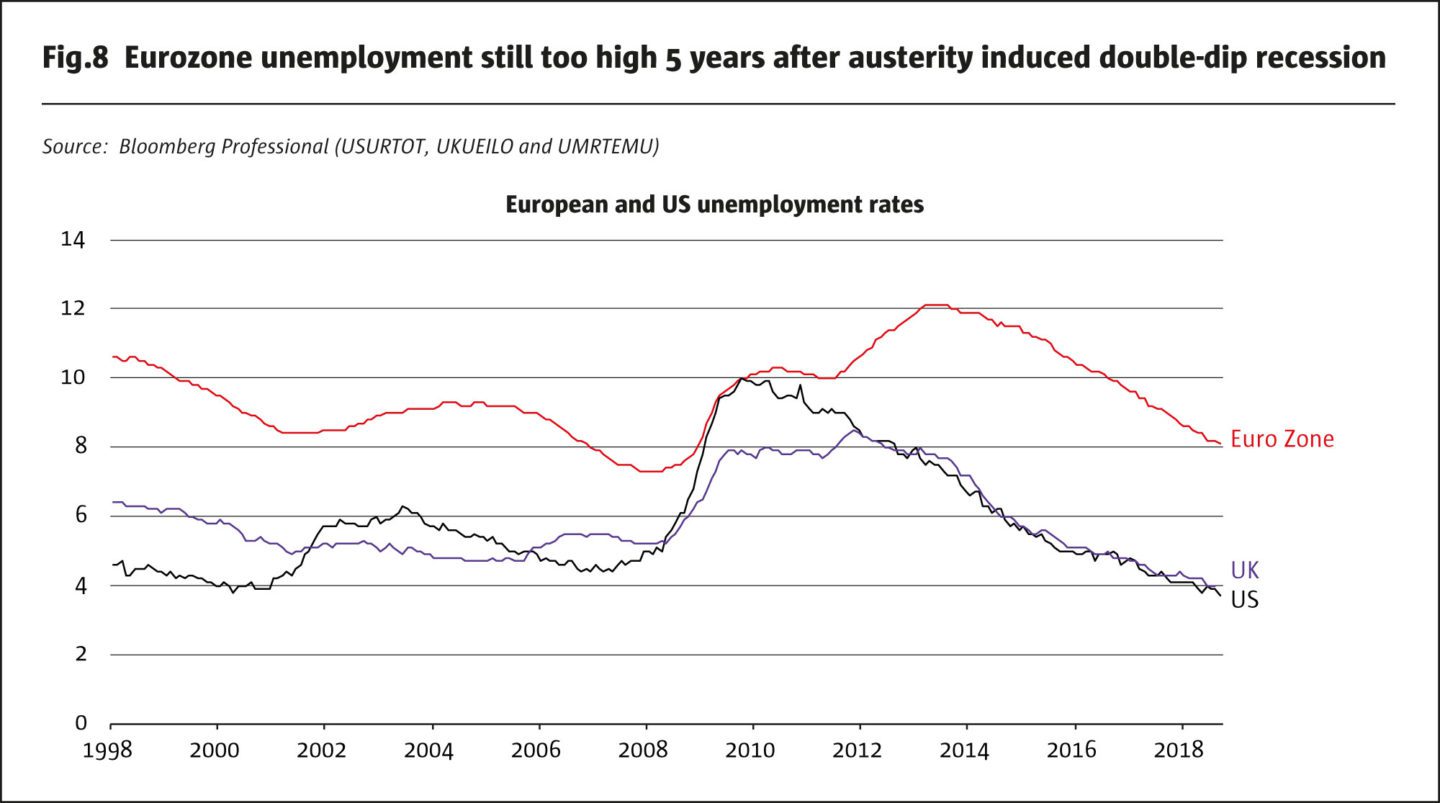

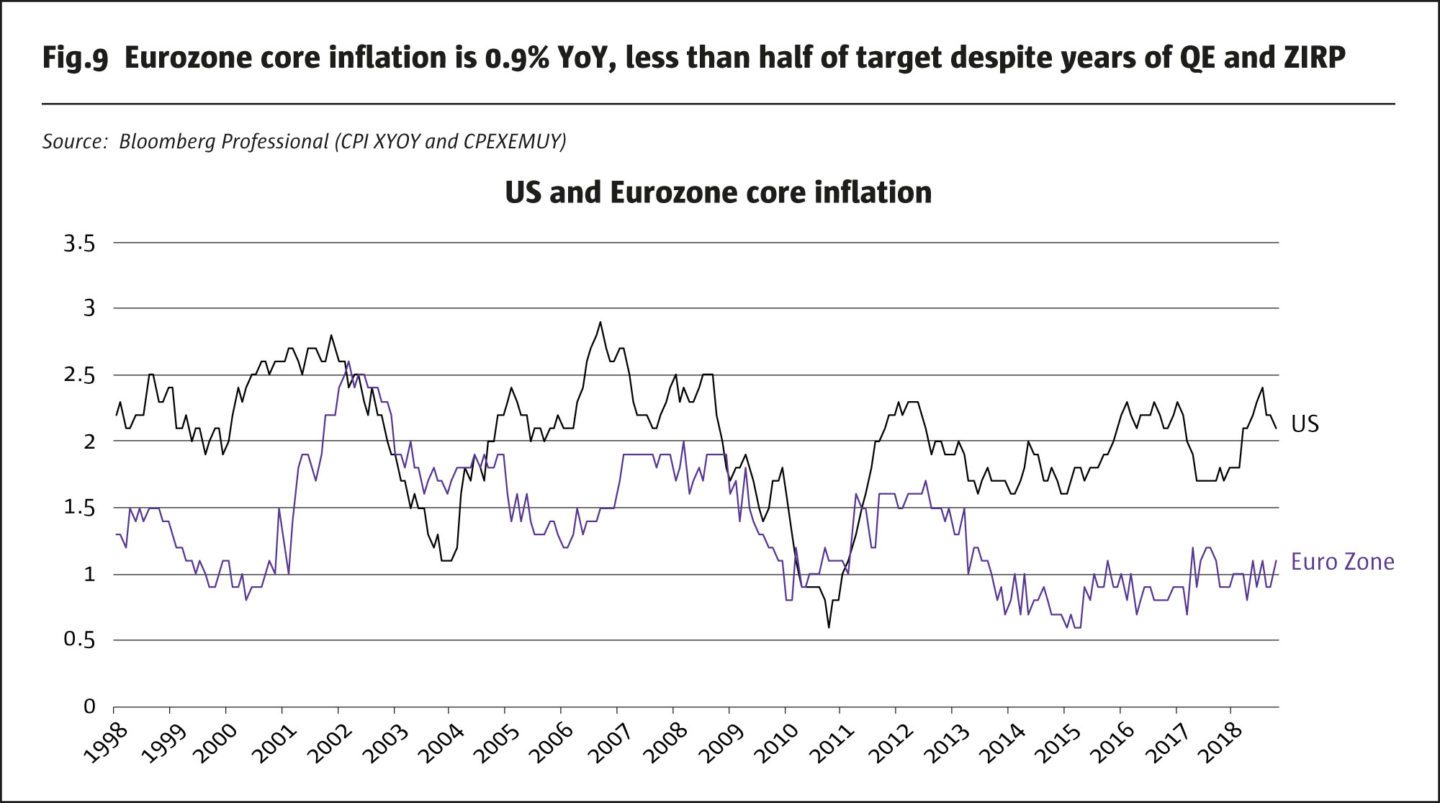

Stronger consumption and investment in Germany would also boost exports to the country and GDP in other European countries, helping to reduce Europe’s still-too-high unemployment rate (Fig.8) and maybe, eventually, help boost Europe’s still-too-low inflation rate towards the ECB’s target of 2% (Fig.9).

Finally, German fiscal expansion will also hasten the day that the ECB is able to normalize policy and increase interest rates. So much of Merkel’s time as Chancellor has been spent making sure that German institutions didn’t have to realize losses on loans made elsewhere in Europe, imposing austerity on the likes of Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

To this end, Merkel only partially succeeded. While those nations, with the notable exception of Greece, have largely made good on their debts so far, Germans had to pay a price. A nation of savers, depositors got nothing other than fees for parking their money in savings accounts. German banks are notoriously unprofitable and shrinking. Pensions struggle to find fixed income investments that give them a positive return, threatening their solvency over the long term. Tax cuts and additional infrastructure spending could lead to higher long-term interest rates, alleviating the problems of pensions over time. The stronger economic growth that would likely stem from an easier fiscal stance could also allow the ECB to end its negative deposit rate policy sooner than it might otherwise to the likely benefit of German banks.

If recent elections elsewhere in Europe are any guide, if the CDU/CSU/SDP coalition doesn’t adopt such policies, the voters might find some other political constellation that will. Greater fiscal spending and tax cuts recently sent bond yields soaring in Italy. In Italy, where public debt is twice as high as in Germany, this isn’t a good thing but in Germany it would be unequivocally positive. On the other side of the pond, short and long-term US interest rates have risen substantially since the US reversed course and began expanding fiscal deficits in 2017. The US, however, has 100% public-debt-to-GDP ratio compared to 60% in Germany and began its fiscal expansion from a 2.2% of GDP deficit rather than a 1.3% of GDP surplus.

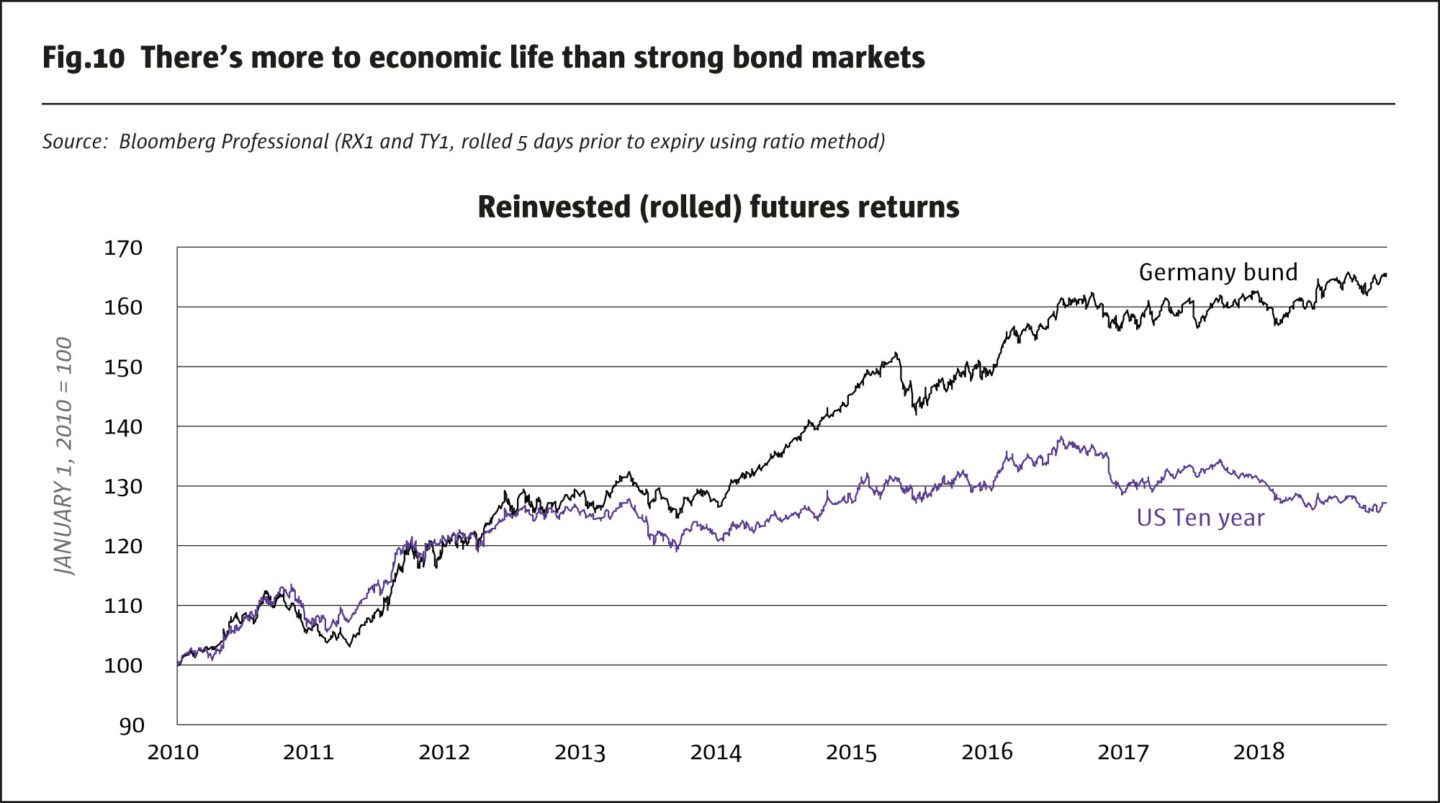

If Germany follows Italy and the US and reverses its tight fiscal stance, the Bund, which has been the best performing bond investment (Fig.10), could go south. If it does, it will almost certainly take yields on French Treasury bonds or OATs and similarly rated European government bonds with it, including the UK Gilt, though it is outside of the Eurozone. It could also release some of the pressure holding down US long-term rates as well. Any change in Germany’s fiscal policy won’t be a small story of local consequence. It will be, at minimum, a European, if not a global, story.

As such, fixed-income investors would do well to watch Merkel’s government closely. Her days as Chancellor could be drawing to a close and with them the days of Germany’s fiscal austerity.

Bottom line

- Angela Merkel’s days as Chancellor are numbered.

- If and when she goes, Germany’s fiscal restraint is likely to go with her.

- If the governing CDU/CSU/SDP coalition doesn’t loosen the fiscal strings, someone else might.

- Once Germany loosens fiscal policy, European economic growth will likely improve.

- Any loosening of Germany’s fiscal position could cause a severe correction in Bunds, putting upward pressure on highly rated yields across Europe and around the globe.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 137

As Merkel Falls, Will Bunds and Treasuries Follow?

Is fiscal restraint likely to go with her?

Erik Norland, Senior Economist and Executive Director, CME Group

Originally published in the December 2018 issue