The Hedge Fund Journal visited the New York offices of Barington Capital Group, L.P. (“Barington”), which follows a “differentiated approach to activist investing” says Partner and Head of Marketing, CFA Charterholder Marjorie Kaufman, who was selected as one of THFJ’s Leading 50 Women In Hedge Funds. Since inception in 2000, Barington’s value-focused activist equity strategy has generated double digit annualised returns, net of fees, and outperformed both the S&P 500 and the Russell 2000 indices, according to an investor.

The strategy primarily invests in the consumer, retail and industrial sectors, almost entirely in the US, and focuses on creating value by helping undervalued companies in its investment portfolio improve their operations, corporate strategy, capital allocation and corporate governance. Barington often finds value in micro, small and mid-cap companies that Kaufman thinks “are often overlooked by some of the largest activist funds”. Boundaries between micro, small and mid-caps are a matter of opinion, but Barington’s range has historically been from The Eastern Company at $100mm in market cap to Darden Restaurants at $6bn, with most holdings above $500mm in market cap, a median of $900mm and all NYSE or Nasdaq listed. Director of Research, CFA Charterholder George Hebard, who has previously worked for Blue Harbour Group and large-cap activist Carl Icahn, is enthused by Barington’s investment approach and the opportunities Barington is pursuing in smaller companies, including Ebix where he sits on the board. The most widely held stocks amongst larger activists and event-driven funds have seldom been present in Barington’s book.

Sometimes Barington blazes a trail followed by other activists and “that’s a net positive as it brings more pressure to bear on a company” says Barington Chairman, CEO and founder James A. Mitarotonda. For instance, Barington privately met with the management of Olive Garden owner Darden Restaurants, Inc. at its Orlando, Florida headquarters in June 2013 and shared with management its value creation plan; wentpublic with its recommendations in October 2013 after it became evident that Darden Chairman and CEO Clarence Otis was resistant to change, and then Starboard Value made a Schedule 13D filing on December 23, 2013. Barington’s pressure on Mr. Otis led to his eventual resignation in 2014, while Starboard ran a successful proxy contest for control of the Darden board. Fast forward to September 2015 and Darden has significantly reduced expenses and entered into sale leaseback transactions and spun off properties into a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT). Cutting costs and unlocking the value of Darden’s sizable real estate holdings were two key elements of Barington’s plan.

Yet Barington has had no trouble effecting changes on its own with smaller positions. “We do not need a large 13D stake to be effective” states Kaufman – indeed Barington and associates’ stake in Darden was approximately 2.5%. “Unique to Barington is our main focus on undervalued situations, where the critical part is identifying an undervalued company and having the skills to design and implement a plan to unlock its value potential” she stresses.

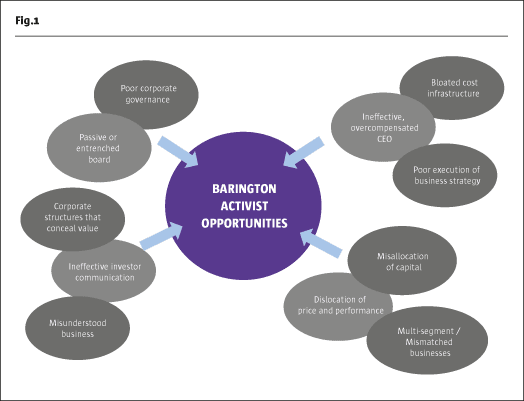

Most Barington investments have been negatively impacted by value destroyers that, if remedied, will help unlock their value potential, as shown below. Though targets may be deeply out of favour, and their share prices might have significantly underperformed their peers and the market as whole for many years, they are not distressed – a typical Barington investment has a strong balance sheet, positive free cash flow and high barriers to entry, all of which help provide downside protection.

Punching Above Its Weight

When some activists argue that their size gives them more clout, and even aim to be the largest minority shareholders, how does Barington punch above its weight? “Our ability to influence boards is based on presenting a very strong, compelling and well thought out case. Experience and reputation also matters; we benefit from having a 15-year track record of partnering with companies to implement plans that have improved long-term value”.

Board Representation

How labour intensive is activism? “Very,” exclaims Mitarotonda. “Our team spends months working to identify an investment opportunity and formulate a plan.” Barington staff, advisory board members or representatives from its network of industry experts also sit on the boards for the majority of its portfolio. For instance, Mitarotonda is currently a director of four outside boards: OMNOVA Solutions Inc.; The Eastern Company; Pep Boys – Manny, Moe & Jack (which recently announced it is being sold to Bridgestone); and A. Schulman, Inc.

While this hands-on involvement is a significant time commitment, Hebard argues that passive managers should be spending almost as much time researching their investments anyway. Mitarotonda finds “being on boards is productive time. It is better to be in the room shaping decisions for the company as this is all part of the process.” Having sat on boards of over a dozen companies, he is well qualified to judge the importance of acting from the inside.

Occasional Proxy Contests

Holding board seats can be associated with various styles of activism. The aggressive, public and hostile activists make so much noise that we all know who they are. Some firms call themselves ‘collaborative activists’ whilst others would prefer to avoid the activist label altogether, calling themselves ‘constructivists’ or ‘engaged investors’. Barington is quite content with the activist moniker and hasbeen predominantly collaborative, but is unusual in covering the full continuum of activist styles, in different situations.

Barington’s preferred approach is to partner with a company’s board of directors and management team as a long-term, value-added investor. However, if Barington’s overtures of assistance are rejected, it may pursue a proxy contest instead and let shareholders decide on the composition of the board. “We are not afraid to take our case directly to shareholders if we get rebuffed by the board,” confirms Mitarotonda. Two recent examples of proxy contests were The Children’s Place and The Eastern Company. In both cases, the proxy contest was not the first course of action. Barington started out acquiring stakes, then proposed plans for creating value, which were resisted by boards. Indeed, Barington spent two years seeking to work collaboratively behind the scenes with Eastern’s Chairman and CEO. Barington’s next step to request board representation was also rebuffed at both companies, so the remaining avenue was to go direct to shareholders. Both proxies were held in May 2015. Barington won two board seats at Eastern, while The Children’s Place settled the proxy contest by making an eleventh hour deal to add Barington nominee Robert L. Mettler to the board, along with Marla Malcolm Beck, a director mutually acceptable to the company and Barington. Harking back to Dillards in 2008, Barington surmounted an extra hurdle and managed to get four new directors added to the board, despite the family’s disproportionate voting powers.

Unique approach: strategically and operationally focused

Barington’s three ingredients of success are valuation, action plans, and execution. On the first point, “you need strong analytical skills to determine if a company is undervalued or not” reflects Mitarotonda. On the second “It is not just about valuing the company but also about making the business better. You have to understand a business as if you were making a private equity investment. To be highly effective you need to thoroughly understand the company, its business, operations, competitors and customers” he adds. Former McKinsey & Company management consultant August M. Vlak is particularly helpful here. The third ingredient of success is execution, and Barington thinks “strategy without execution is hallucination”.

Actionable plans can take many forms. Some activists are perceived as emphasising operational improvements and others as majoring on financial engineering but the reality is that activists work on targets from many angles. Barington is no exception, although the firm has not been involved in any deals that were aiming for tax inversions. Barington finds there is often room for many types of improvements and does not follow any fixed, cookie cutter, formula. Says Mitarotonda “we first focus on the company and all aspects of its operations”. Cost-cutting, consolidation and working capital optimisation are examples of operational improvements that can keep a corporate structure intact, and some forms of restructuring can reallocate capital within a firm’s existing divisions. Sometimes more radical action is needed through strategic changes, such as divesting non-core assets. Mitarotonda recalls Stewart & Stevenson Services, a firm where four of its five businesses which were unprofitable or non-core were sold for Barington’s entry valuation of $400 million in market capitalization, meaning that the remaining core business unit was effectively acquired for free, and the stock tripled in two years.

Finally, Barington recognises that corporate governance improvements are often necessary to facilitate the effectiveness of its strategic and operating recommendations. According to Jared Landaw, Barington’s COO and General Counsel, “we look carefully and the company’s we are investing in – most of whom have underperformed the market and their peers for a substantial period of time – to determine why they have not made the necessary changes on their own. More often than not, there are corporate governance concerns that have been negatively impacting the company.” Corporate governance improvements could include the appointment of an independent chairman or eliminating a staggered board or plurality voting.

‘Main Street’ experience

To implement operational advances, Mitarotonda prizes real world business experience, and his own career has included ‘Main Street’ as well as ‘Wall Street’. Starting at fashion retailer Bloomingdales, his second job was at Citibank consumer banking. Hebard, too, has industrial belt-notches including an extreme experience of corporate downsizing while working as Interim Principal Executive Officer of Enzon Pharmaceuticals, an investment of Carl Ichan: he took staff down to one from 50 at a a biotech that had to be wound down after a drug did not work. Landaw was an officer at International Specialty Products, a specialty chemicals company controlled by noted activist investor Samuel J. Heyman.

As well as its medium-sized team of nine internally, Barington draws on external expertise that is tailored to each individual target company. Barington’s advisory board members have all been involved in advising and running businesses from the inside. “Our hands-on experience means we understand those on the other side of the table,” Mitarotonda argues. Barington also brings strong investment banking and capital markets knowledge to bear, benefiting from its heritage as a full-service advisory boutique: Barington was originally founded in 1992 as an investment bank specialising in small caps, and it underwrote 30 Initial Public Offerings (IPOs).

Long Term Vision

Beyond the formal advisory board, Mitarotonda has long-term relationships with its own extended network of industry contacts – but does not use expert networks. “We do our own proprietary research utilising our network of industry experts, which includes former executives with experience in the industries in which we invest.” Barington also taps this network to find experienced public company directors, like Westlake Chemical director Max L. Lukens and former Macy West’s Chairman and CEO Robert Mettler, to put on to boards.

Close oversight of, and dialogue with, companies renders Barington restricted from trading during closed periods but this does not cramp Barington’s style because “it is not a short term trading strategy. We typically often invest for two to five years and sometimes for even longer, with an average holding period of three years” Mitarotonda recalls, noting that “management of companies like Barington’s long-term commitment.”

Barington has been able to exit from holdings where the investment thesis turned out wrong. Most activists have at least one or two ‘war stories’ of losses, and one of Barington’s losers was also one of Pershing Square’s worst investments: book retailer Borders. In late 2006, Barington had thought that, despite the declining book market, Borders might be able to survive by rationalising its operations – selling off non-core UK and US divisions in order to focus on running its core US stores. But when a new CEO from Saks Department Store Group resolved to expand the chain with new stores and product ranges, Barington sold out at an average price of approximately $16 a share for a loss of about 15%. The stock, and Bill Ackman’s holding in it, later went to zero when Borders went bankrupt (Ackman had earlier attempted to use Borders as an acquisition vehicle for Barnes and Noble). Thomson SA was Barington’s other memorable loser. Thomson was sold at approximately €8 per share for a loss of around 40% after its DVD replication and other businesses shrank faster than expected; the stock fell further after Barington bailed out.

Barington is finding no shortage of potential investment opportunities in late 2015. “We are extremely excited about the opportunities we are working on” states Mitarotonda.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical