Returns from Asia-Pacific merger arbitrage positions have proved consistently attractive over time, offering the additional benefit of portfolio diversification when compared to other equity strategies where returns are more susceptible to the vagaries of market cycles.

With a new wave of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity and promoter-led take-private deals, buoyed in some key markets by heightened geopolitical tensions, merger arbitrage thrives as an investment strategy for well-prepared investors. Cash-rich companies that have weathered COVID-19, opportunistic family controllers and private equity firms now sitting on record levels of dry powder are creating attractive merger arbitrage opportunities. These investors are focusing on businesses in distress and takeovers or privatizations of companies which are currently undervalued by the market.

In this alert, we highlight some of the key questions investors consider when analysing merger arbitrage investment opportunities in the key public M&A markets in the Asia Pacific region.

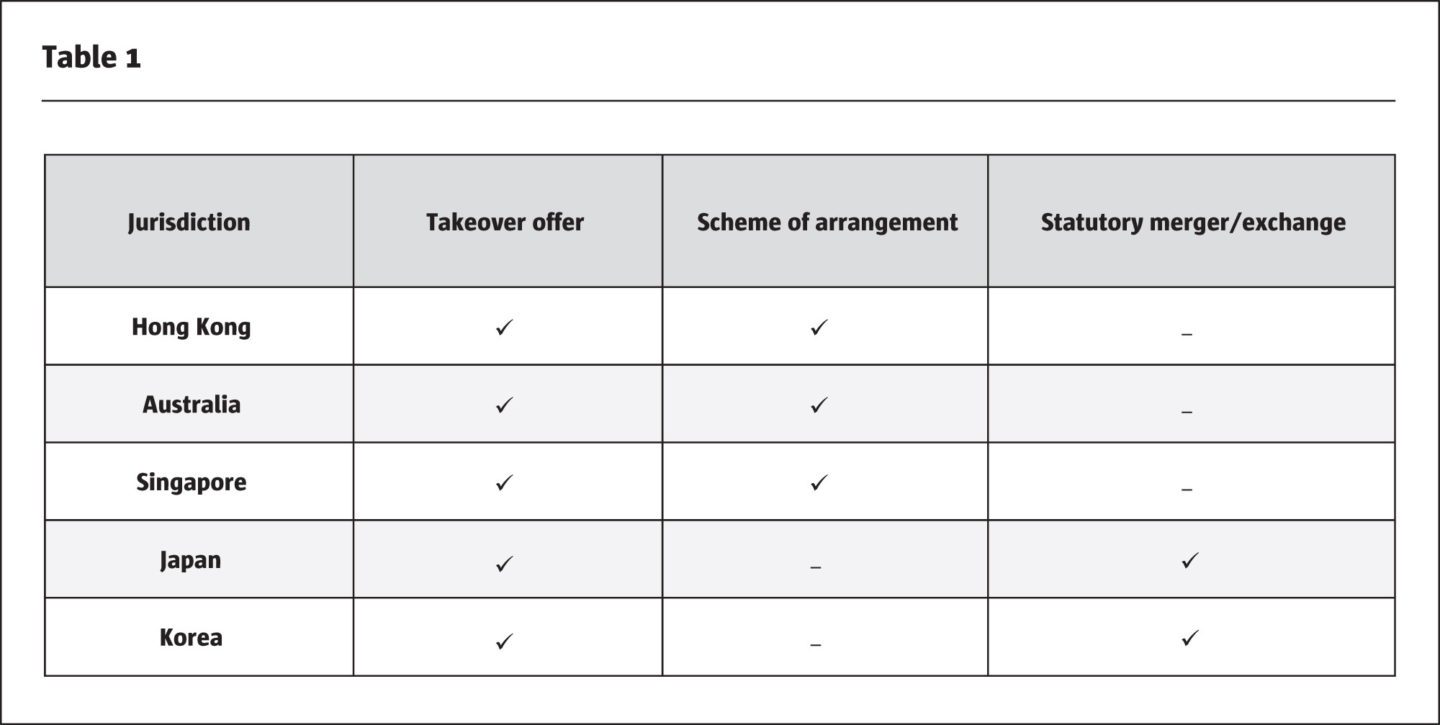

1. What are the primary methods of acquiring or consolidating control of this publicly listed company target? See Table 1

An essential consideration in formulating the investment strategy is understanding the process by which the acquisition is to be undertaken. This drives various key investment considerations, including deal risk (e.g., approval thresholds and minority squeeze-out) and the likely investment timeline.

Key issues to consider

Although uncommon, it is possible for an acquisition to switch from execution by way of a scheme of arrangement or statutory merger/exchange to a takeover (tender) offer. This may be the case where, for example, the target becomes subject to a competing bid or if the target board otherwise withdraws its approval for the acquisition, leading to a hostile bid situation.

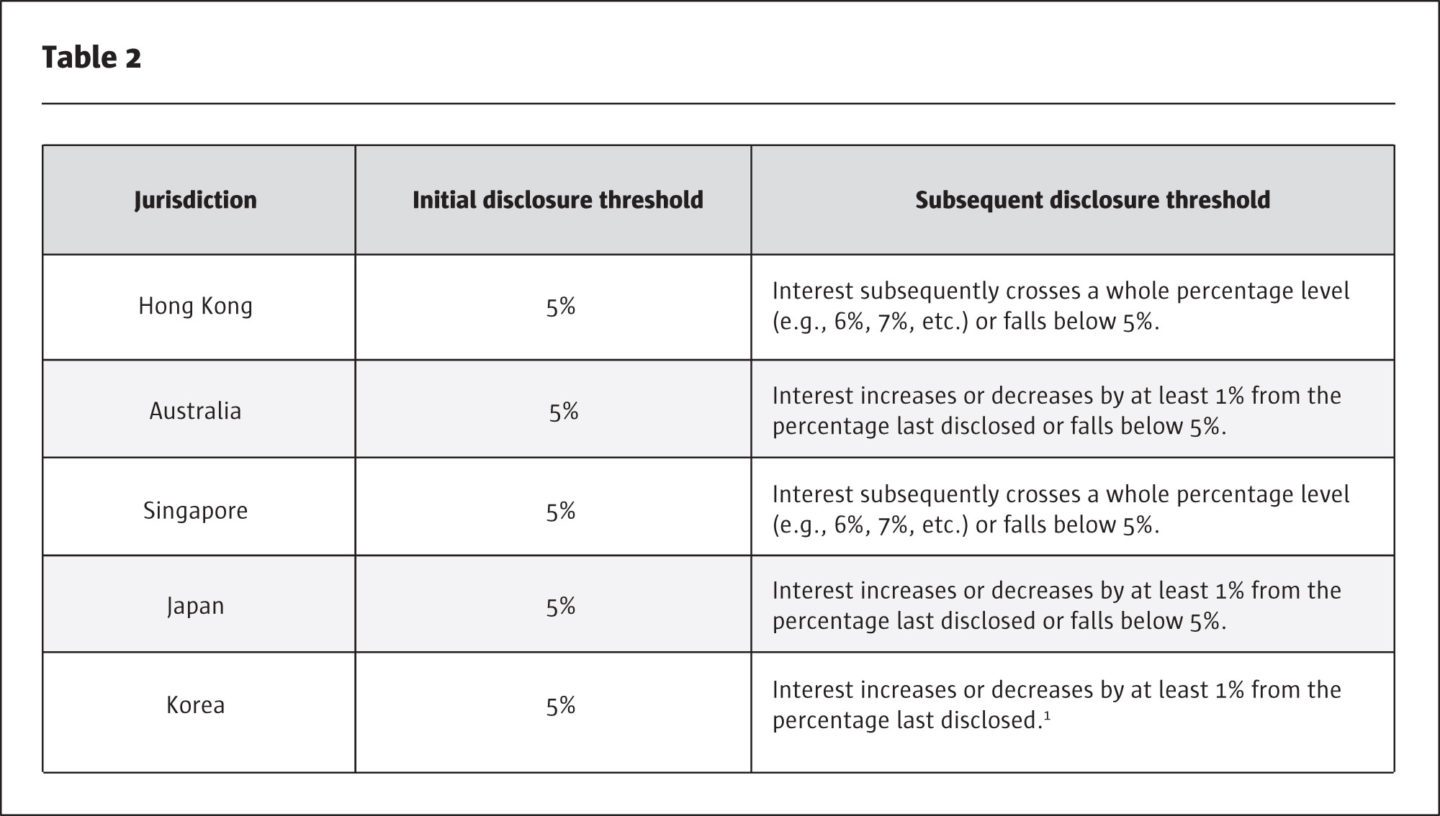

2. Will my investment in this publicly listed target company be disclosed to the market? See Table 2

Publicly available position reporting can be a strategically critical and valuesensitive issue for merger arbitrage investors. In Asia, the disclosure rules for equity interests can be complex and require careful analysis on a case-by-case basis.

Key issues to consider

Of the jurisdictions covered in the table above, Hong Kong and Singapore represent the high-water mark for disclosures, in the sense that they require most material equity interests, not just share ownership, to be publicly disclosed. In Japan and Korea, on the other hand, certain properly structured equity swaps and other forms of equity exposure may not need to be publicly disclosed. It is essential to carefully consider the nature of the proposed equity exposure instruments and the circumstances in which they are acquired and unwound, including any related short positions, which may trigger separate disclosure obligations.

Investors should also look out for U.S.-listed American depositary receipts (ADRs), which are common for Asia-Pacific issuers, as these can give rise to separate U.S. securities reporting to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—potentially resulting in a disclosure obligation at sub-five percent for investors who are required to report as a result of Section 13(f) of the U.S. Securities Exchange Act.2 In some jurisdictions, any dealings in relevant securities by target shareholders who already hold five percent or more during an offer period may also trigger a disclosure.

3. Will the antitrust, foreign investment or other authorities object to or delay the deal?

Most deal parties will only invest the significant level of resources required to get a transaction to the stage of public announcement if they are reasonably sure that the deal will pass any applicable antitrust approvals and clear any other key regulatory hurdles. However, depending on the profile of the target, the relevant markets and, of course, the acquirer, there can be significant regulatory risk in terms of whether the deal will be approved or not and, if so, how long the approvals will take and whether they may be conditional upon divestitures, compulsory licensing or other remedies which could undermine deal synergies. This is especially so in the context of the heightened levels of geopolitical tensions that we have witnessed in the last few years.

Key antitrust and foreign investment jurisdictions to consider include China, South Korea, Japan, India, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia and Vietnam. Asian antitrust and other regulatory risks can materially impact the returns from a merger arbitrage strategy – not just with respect to Asian targets, but also targets headquartered in the US or Europe with activities in Asia. Legal analysis of the relevant regulatory variables, and the corresponding probability and likely timing of approval/clearance, can help bolster investors’ returns by removing much of the guesswork from these key risk factors.

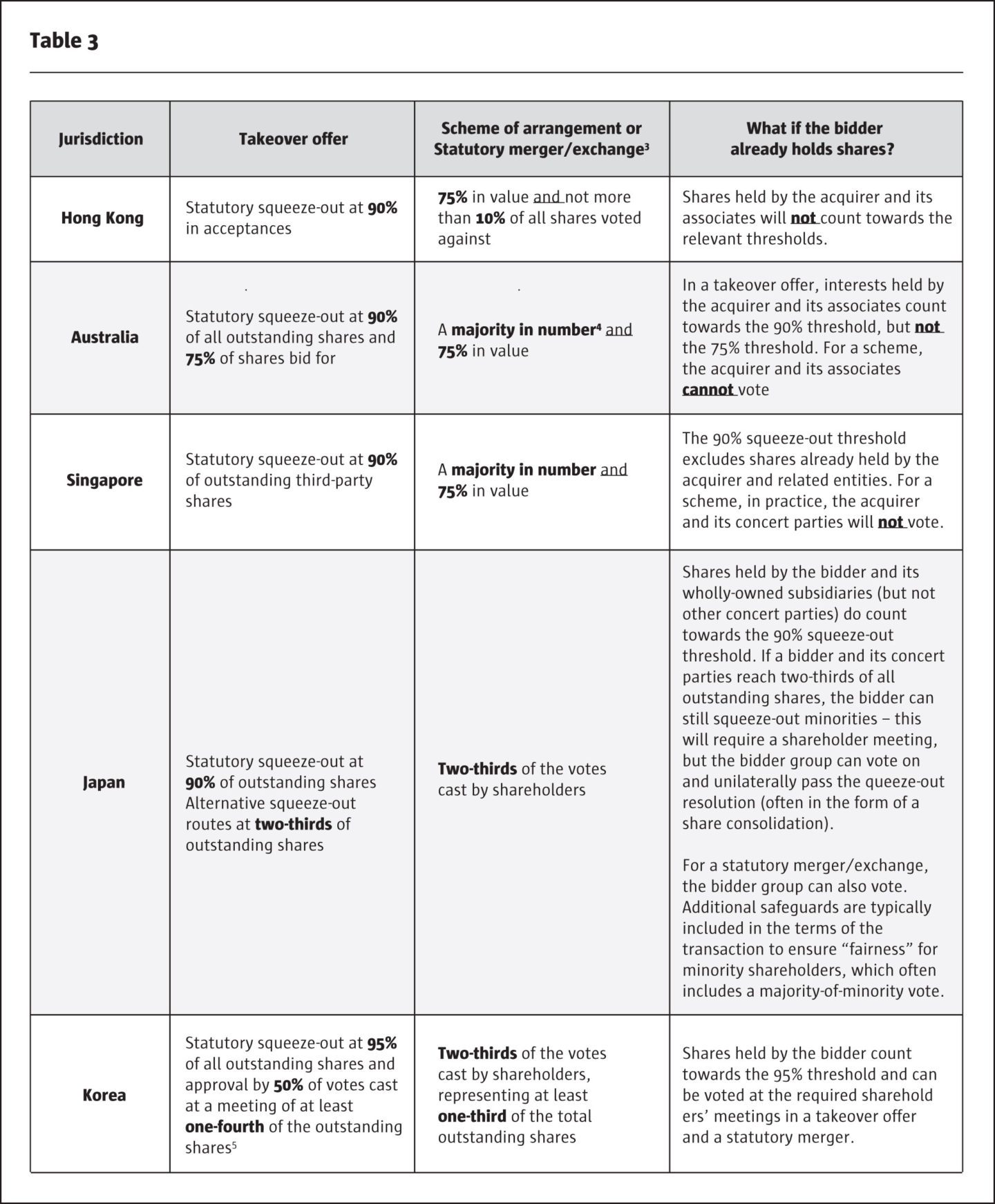

4. How easy is it for minority investors to block the takeover or privatization offer? See Table 3

The rights and ability of minority investors to block a takeover or take-private deal are fundamental to the proper assessment of merger arbitrage deal risk and the success of more activist merger arbitrage strategies. For schemes of arrangement and statutory mergers/exchanges, the ability to block a deal is driven by the applicable thresholds for shareholder approval of the transaction, once it has been approved by the requisite majority (and, in the case of schemes, sanctioned by the court), all target shareholders will be bound by the acquisition. For takeover offerors seeking 100 percent ownership of the target, the position with respect to dissenting minorities will depend on the ownership level at which the acquirer can squeeze out any hold-outs.

Key issues to consider

The number of shares required by minority investors in the target company to block a scheme or statutory merger/exchange is typically much lower in practice than the percentages implied by the table above, since the voting thresholds are often based on the percentage of votes cast on the resolution, rather than of all shareholders6 . Careful consideration should be given to factors such as whether the bidder has an existing stake, typical voter turnout levels and overall share register composition when assessing deliverability of the transaction(s) in hand. If the acquirer or its related parties are already shareholders of the target, which will typically be the case in a take-private deal, their ability to vote on the transaction or count towards the required thresholds to squeeze out minorities can play a fundamental role in determining the level of acceptance required from the disinterested shareholders and therefore the associated deal risk.

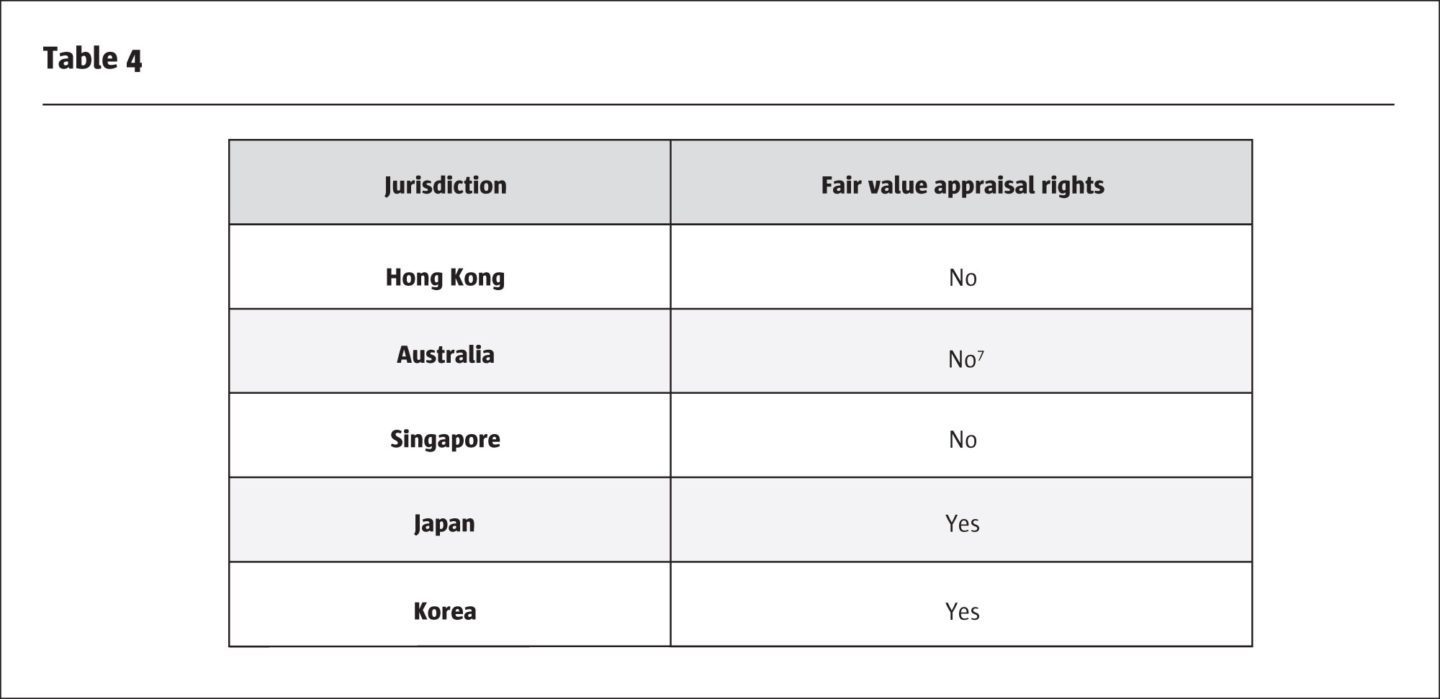

5. Do objecting minorities have appraisal rights? See Table 4

One added protection available to dissenting shareholders in certain jurisdictions is the ability to exercise appraisal rights, which entitles such dissenters who satisfy relevant statutory requirements to be paid the “fair value” for their shares, on the basis determined by the local court.

Practice point

Not all issuers are incorporated where they have significant operations or are listed. The legal regimes in some common “offshore” jurisdictions of incorporation, such as the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands and Bermuda, include statutory appraisal right mechanisms, which may well be relevant to a take-private or merger transaction, regardless of where the company conducts business or is listed.

A solid understanding of factors such as those outlined above is key to identifying and capitalizing on the increasing number of merger arbitrage and similar investment opportunities across the Asia-Pacific region. With advice and guidance from in-market legal specialists, investors can navigate the key valueimpacting legal and regulatory issues across the unique and varied M&A markets in the region.

Footnotes

- If a shareholder and any related parties acquire five percent or more of the total voting shares of a target company off-market from 10 or more persons within a six-month period, such shareholder must make a public tender offer. If a shareholder holds 10% or more of the total shares of a company, any subsequent increase or decrease of any size (even one share) will need to be publicly disclosed.

- Note that Section 13(f) reporting may become less relevant for a number of investors in light of the SEC’s proposed increase of the reporting threshold from US$100 million to US$3.5 billion (more information available here).

- Thresholds are calculated on the basis of votes cast by shareholders attending and voting at the relevant shareholder meeting, unless otherwise stated.

- It is possible for a court to waive this requirement.

- In practice, dissenting minority shareholders may be able to block a squeeze-out, for instance, by filing a preliminary injunction for a court order to prevent the adoption of resolutions at the shareholders’ meeting on the basis that there is no valid business purpose in the compulsory acquisition. Therefore, the shareholders’ meeting is not an entirely procedural requirement, notwithstanding that the bidder and its related parties have acquired at least 95 percent of the total shares of the target company.

- However, it is worth reiterating that for a statutory merger in Korea, the one-third threshold is based on all outstanding shares – ensuring a minimum shareholder turnout threshold for the merger to be approved

- Whilst there is no formal appraisal rights process, a minority shareholder can apply to the court to prevent the compulsory acquisition of its shares. The court can only make this order if it determines that the consideration for the compulsory acquisition is not fair value.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical