Many investors have fallen out of love with equity investing. High volatility and drawdowns have seen institutional players cut back on the equities component of their portfolios. Against that backdrop the success of Cevian Capital is all the more intriguing. A testament to its performance is that it has continued to strengthen its capital base during the recent volatility in financial markets. That’s helped it move up to 15th in the 2012 Europe 50 ranking of leading hedge funds with assets under management of $7 billion compared to a ranking of 39th with AUM of $3.25 billion when it first appeared in the 2007 survey.

Fiveyears ago Cevian ranked about 15th in terms of European equity managers by amount of AUM. Even though investors have reduced exposure to equities, Cevian has grown and now resides among the top five European hedge fund firms in terms of AUM invested in shares. As Cevian’s investment footprint has grown, so too has its senior team, which includes nine equity owning partners among a team numbering 21 investment professionals. This is nearly treble the number from when the current fund Cevian Capital II launched in 2006. It also makes Cevian among the best resourced and most experienced activist teams anywhere.

Constructive activism

Cevian’s continued success has placed it at the vanguard of activist firms. Cevian Capital II has returned approximately 119% since launch, while the MSCI Europe index has returned 4% over the same period. Since 1996, Cevian has sat on over 20 company boards in six different countries, but has never engaged in a proxy fight. Instead, the firm bills itself as a ‘constructive activist’ that looks to work with other shareholders, perhaps including other hedge funds, as well as managers and institutional stock owners. The overriding aim is to improve a company’s performance so that it will get more highly valued by the market and be worth more to investors. Thus Cevian’s focus is on generating returns by effecting long-term operational change instead of maximising gains by short-term portfolio trading. This discipline is the result of its co-founders Christer Gardell and Lars Förberg being drawn from the ranks of management consultancy and private equity rather than trading desks.

“Our strategy aims to take advantage of and arbitrage the irrational and increasingly short-term behaviour in the public markets by being a long-term investor with a concentrated portfolio and active ownership approach,” says Gardell. “We get deeply engaged with companies and about 50% of the time we join the boards of firms with which we have invested. The distinguishing feature in our strategy is that as long-term investors the operational aspects of the value enhancement plan are usually the most important. We are looking at opportunities where we can increase the margin from, perhaps, 5% to 10% or more.”

“One aspect of success is performance,” says Gardell. “But whenever we get in, it should become a strong company and performing better versus the competition. The idea of taking an underperformer and making it a better performer than its peers is a key part of our strategy.”

The stability of capital at Cevian meant that during the 2008-09 down turn the fund didn’t need to gate or suspend redemptions. Instead, it enabled Cevian to go on the offensive at a time when other investors had to be defensive and, in many cases, return capital to investors. Strong performance and a record free from the blemishes that plagued many others in the downturn have been rewarded with a steady inflow of capital from investors. Pension funds now account for approximately one-third of AUM, reflecting Cevian’s growing maturity. A public record search identifies a number of large state and national pension funds as investors, such as the Canadian Pension Plan, the Swedish State AP1 pension fund, and public plans from the states of Florida, New York, New Jersey, Virginia and Ohio.

Getting started

Förberg and Gardell met in early 1990s Stockholm. Förberg was the first employee hired by the partners who founded Nordic Capital, a private equity firm headquartered in Sweden. The firm tasked Gardell, then a partner with management consultants McKinsey & Co., to run due diligence on a potential acquisition. He ended up joining the privateequity firm. Not long after that Custos, a listed Swedish industrial holding company, recruited Gardell to be CEO. That occasioned Förberg joining as Chief Investment Officer.

It was at Custos, starting in 1996, that the pair developed and implemented the strategy of taking minority positions in listed companies that were fundamentally sound but underperforming their potential. The aim was to revamp a company and get substantial returns over a three to five-year period. The approach was designed to get around the problem of having to pay a premium to win control or not do anything. Why not, the thinking went, buy a 10%-plus stake and work with the various stakeholders to effect change? The co-founders had complimentary skills combining Förberg’s private equity background and Gardell’s experience in restructuring and advising on turnarounds from his time at McKinsey.

Förberg and Gardell spun out of Custos in 2001 to execute the strategy at their own firm, Cevian Capital and launched Cevian Capital I in 2002. The first investment was northern European fashion retailer Lindex where a 15% stake was acquired. A second investment soon followed with a 10%-plus stake in Intrum Justitia, Europe’s largest debt collection company. What occurred here laid the groundwork for much of what was to follow. Cevian took lead board positions and began to implement change. The two investments were held for over four years during which time the stock price appreciated significantly. The operating margin at Lindex jumped to 12% from 4.5%, while that metric at Intrum Justitia rose to 20% from 13% with growth prospects enhanced too. Investors recognised Cevian Capital I’s strong record and oversubscribed the 2006 launch of Cevian Capital II with €1.5 billion.

Enhancing value

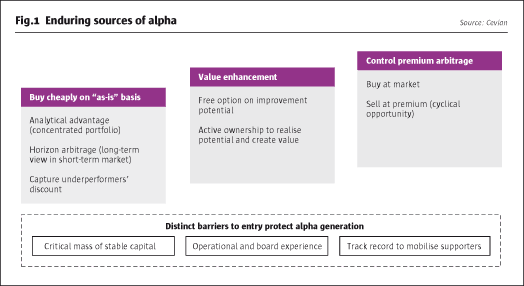

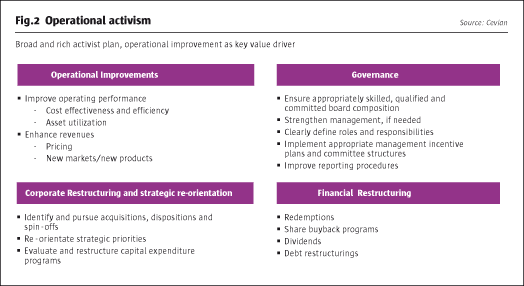

With Cevian, the general framework is to look for value enhancement in four areas. The areas include:

– operational improvements

– strategic re-orientation or corporate restructuring

– financial restructuring

– improvements to corporate governance.

Even before Cevian invests it is keen to see that improvements are planned or have begun in these areas. It generally operates with a three-year time frame to improve a business. The investment target is a 100% gain over three years, driven primarily by Cevian’s value enhancement measures and strong company fundamentals. Operational improvement is the most important area to effect change. However, sometimes to get operating gains it may be necessary to reconstitute a company’s board and change its management.

“We don’t look to have one big idea,” says Förberg. “It is too risky. We like to have a broad set of different ideas in all of these buckets because that will see risk reduced. We might not get all changes implemented but a majority would generally be good enough to get the returns we seek.”

The contrast with a traditional activism is clear. Typically, an activist will work on a target company’s balance sheet, perhaps to secure a special dividend. Alternatively, it might look to put a company into play in order to have a suitor pay a premium for a takeover. Using a variety of means, including proxy battles and highly vocal media campaigns, the traditional activist seeks to put pressure on a company’s management and secure some type of value enhancement.

In contrast, Cevian’s approach is more nuanced and constructive. “Our core strategy is to improve the fundamental earnings and value of the company,” Förberg says. “That differs from the traditional activist. We do this in a constructive but assertive manner. That is a strategy and a style that resonates much better than a hostile approach with the culturalbackdrop of the markets where we operate. A constructive approach is a more productive and effective strategy to improve a company and be successful. The good thing is that the strategy is a virtuous circle. If we show that we can fundamentally improve companies then we will get support from the other important stakeholders in companies where we get involved.”

Targeting German companies

Central to Cevian’s origins is the fact that the active ownership model was pioneered in Scandinavia. By 2006, the firm had a decade of experience in using the model to implement changes in companies’ operations, governance and corporate structure. It was a natural extension to apply the successful approach to other countries in northern Europe with strong corporate governance regimes, notably Germany, where the pace of corporate change and restructuring was increasing.

Beginning in the 1990s, Scandinavian companies had faced pressure to improve their performance and eliminate conglomerate structures. In Europe, notably in the German-speaking region, this hadn’t been the case. Instead, ownership structures remained fragmented. With shareholders only owning a small percentage of a business they either weren’t inclined or lacked the means to put pressure on companies’ boards to improve performance and boost returns. Moreover, German industry was still characterised by a large number of conglomerates, something that Cevian had worked to change in Finland and Sweden. Like Scandinavia, Germany had a big engineering sector and many of those companies had competitors to the north that Cevian knew well. So in 2007, Förberg moved to Zurich where the firm set up an office to focus on the German-speaking market.

“Expanding into the continent utilised a lot of investment knowledge we built up,” says Gardell. “Germany has excellent companies with very strong products and a leading market position in the global economy. But because they have not been exposed to the pressure that is exerted in Scandinavia there is a lot of unrealised potential to improve operational performance. We also see that some of these companies have corporate structures that are quite diversified and would benefit from simplified structures. We see quite a few of these kinds of opportunities in Germany.”

Portfolio characteristics

At any given time, Cevian will have around 10 to 12 portfolio companies. The investment team look at the entire market to get a short list of the best opportunities. On average, two or three investments are made each year. To get into the portfolio, the investment must offer the potential to outperform something that is already there. In short, the investment team must decide that an opportunity is more attractive than the marginal company in the portfolio. When a new idea is being considered for the portfolio it means that there are always two decisions. One is to invest, the other is to divest since the portfolio is generally fully invested.

Decision making occurs through coordination committee meetings held every month. Every position in the portfolio is reviewed and new investment opportunities are discussed. The criteria to unwind an investment are usually based on estimates of remaining value to be realised. Though there can be a number of time horizons for holding a position, the most likely scenario is that an older position in the portfolio will be unwound for a new one to be opened.

Cevian methodology

A consistent investment process lies at the heart of Cevian’s approach. For an investment opportunity to move forward, a company must be cheap on an ‘as-is’ basis.

“The out of favour angle is important,” says Gardell. “We also need to feel there is a rich and realistic value enhancement plan. These two elements should be in place. We also test the realism of the value enhancement plan. Can we improve the business? Or will it always be cheap on an ‘as-is’ basis? A lot of discussion will focus on whether the desired actions are realistic and whether the corporate governance structure makes it realistic to improve the business over a three-year time frame.”

The consistent investment process means that the same rigorous due diligence steps are taken across the firm. The first stage in finding and analysing opportunities is commissioning a five page report. If the senior investment team likes the thesis, deep fundamental research leading to a 40 page report is commissioned. If the research for that draws a favourable response then full blown due-diligence ensues, leading to a comprehensive 140 page report. This serves as a decision making document and road map for the value enhancement work.

This phase involves four to six months of investigation, occasioning deep digging into a business. The process would involve talking to the company, competitors, suppliers, customers and industry analysts; in sum, maybe 75-100 different people with a wide range of knowledge of the business. Yet as the report becomes more in-depth the investment test remains focused on the relative value of the assets and how that can be augmented.

Since Cevian doesn’t use shorting and has a tightly focused portfolio, each investment is very important to the overall fund performance. It is therefore extremely careful with the investments it undertakes. The need to locate value overlooked by the market is the key to being able to withstand volatility in the market when that erupts.

“We are very risk-averse,” says Gardell. “The risk/return template we use aims for a worst case scenario of a maximum 20% loss. In every investment we like to see a realistic opportunity to double the investment value over the three-year time frame. That is the risk/return template we are applying.” If future demand outlook is too uncertain, say in a business like the Yellow pages, or paper manufacturing, Cevian won’t get involved. However, because of its successful track record when Cevian does emerge as a shareholder in a company there is usually a pop in the stock price.

Active in the UK

Cevian’s most recent investment in Britain is Cookson Group, the industrial materials producer. Beginning in the fourth quarter of 2011 Cevian began building what is now a 20% stake in Cookson. Though the stock is off the 52-week highs above 700 pence recorded in April, it is still up over 35% from when Cevian initially disclosed its stake through the end of September. Here Cevian showed impeccable timing as its first public disclosure of the stake came just days after a 10 November 2011 interim management statement when Cookson said “the Group’s overall performance in the second half of the year (is expected) to be slightly below that of the first half.”

Even with that weaker outlook, the financial logic of the investment is straightforward. Cookson trades on a prospective price/earnings ratio of just eight and is therefore at a significant discount to peers. In addition, Cookson runs ceramics and electronics divisions which deliver few operating synergies. In recent months, Gardell has joined Cookson as a non-executive director and the company is now formally considering a demerger. Here the plan is to sharpen operating focus and give investors a share in two specialised companies which should be worth more than one share in a conglomerate-like company. “We think Cookson is a misunderstood business,” says Gardell. “The valuation is very attractive. We saw a very good opportunity for value enhancement.”

The approach Cevian took to the UK is instructive to how it adapts to different markets. In 2007, it opened a small office in London with a senior investment professional, Harlan Zimmerman, and began to build links with UK-based institutional investors and raise Cevian’s British profile. This was extended with the appointment of Lord Myners as a partner and chairman of Cevian Capital (UK) LLP in May 2011. Myners is a noted board room leader and, as a government minister, led the restructuring of the UK banking sector. He is known for highlighting ‘ownerless corporations’ as a source of corporate underperformance, and for calling upon asset owners and managers to be more active owners. Cevian is thus close to the heart of the UK institutional investor community.

“To work our strategy in the UK market we need to communicate to other institutional shareholders about what we are doing and why this could be good for them and for us,” says Gardell. “We have spent a lot of time interacting with UK institutional investors. It has had good results. When I joined the Cookson board it was supported by the other shareholders.”

Teliasonera

One of Cevian’s most high-profile investments was in Teliasonera, the incumbent Scandinavian telecoms provider. The firm’s strong position in its home markets was offset by a weak governance structure and an ineffective board. Then, with no forewarning to the market, Teliasonera announced plans in 2006 for a new mobile business in Spain involving high capital expenditure. Shareholders rebelled and the stock price fell. During the sell-off Cevian built a position as earlier research had spotted operational improvements that could boost value in the core Nordic business. Doubts about the wisdom of the Spanish strategy proved to be a catalyst to Cevian working with other top-four shareholders, including the Swedish government, to reform the telecom firm’s governance.

“For us it was important to convince the other large shareholders that we needed to act on corporate governance,” recalls Gardell. In this case, Gardell joined the company’s nominations committee which shortly thereafter decided to call an extraordinary shareholders meeting. In that meeting, five of eight directors were removed and four new directors, who had relevant experience, came in. This included two people whom Cevian had worked with previously.

The new board subsequently installed Lars Nyberg as the new Chief Executive, who then put in his own team. A 20% head count reduction pared costs and helped add 5% to the company’s margin, bringing Teliasonera back into favour with investors. By 2009, Cevian decided to wind down the stake and take new positions offering better opportunities to build value following the Lehman collapse. Despite the investment spanning a severe equity bear market, the return on Teliasonera was 60%, beating indices by a wide margin.

Appropriate capital structure

The fund’s capital base and lock-up structure proved paramount to negotiating the extraordinarily difficult market conditions of 2008-2009. “The structure means we won’t be forced to panic and exit our positions,” says Gardell. “When the turbulence happened our capital structure remained long-term and we didn’t need to use gates or side pockets. Instead, we could use the downturn as a tailwind to speed up the value enhancement work at our companies. Also we made a number of new investments during that phase when valuations were very attractive.”

Unsurprisingly, Cevian has proved particularly attractive to experienced hedge fund investors. Such investors realise that the current vogue for weekly or monthly liquidity terms is wholly unsuitable to Cevian’s operational activist strategy. The Cevian II fund has proven particularly successful at raising capital from North American pension funds.

“First of all it is important to have investors that understand our strategy and that are long-term,” says Gardell. “And it seems that most of the long-term capital is North American. They are further along the experience curve than some of the European investors.”

Cevian’s patience and operational focus means that it has never been involved in a proxy battle. Working with companies and boards has generally succeeded in Cevian getting its carefully devised improvements accepted by stakeholders.

“Historically we have been successful in getting this across,” adds Gardell. “We are a bit more patient than some other investors who may have a short time horizon which may lead them to force the issue with a proxy fight. Sometimes there are difficult decisions. But it is not a matter of compromising on the plan we have, it just takes a little longer to get there.”

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical