The launch of the Cevian Capital II Fund in the middle of last year was a signal event for the managers of Cevian Capital. In 2006 event-driven funds raised a total of $8.5 billion of new capital, four times more than in 2005, and Cevian Capital II drew $2 billion of it in June. The majority of the capital raised came from US investors such as endowments, pension funds, institutions and family offices. They then had another round of capital raising a year later and took in another $2 billion of capital. The investors include old hands like Carl Icahn, and the newer sources of capital for hedge funds like AP1, the largest government pension fund in Sweden.

AP1’s investments with Cevian have been described as its first true hedge fund investment. But the logical case for AP1’s commitment of capital is clear – Cevian 1 (the predecessor fund) had produced an average annual return of 78%. AP1’s Head of Alternatives Sofia Ericsson has stressed that the investment should not be viewed as part of any overall hedge fund investment strategy: “We are an investor in Cevian’s first fund and have been very happy with the returns so far. AP1’s investment in Cevian should be viewed as an individual investment decision, not as part of a hedge fund strategy. AP1 does not have a hedge fund strategy and we are not likely to invest in other hedge funds currently.” So what is it that Cevian Capital and founders Christer Gardell and Lars Förberg do to produce such returns, and why are they considered a special case for investments by serious investors like AP1?

(L-R) Lars Förberg, Christer Gardell

Finding one another

Gardell and Förberg first came across one another in 1992 when Christer Gardell was working for McKinsey & Co. In his 11 years with McKinsey in Australia and Scandinavia Gardell had worked on a variety of assignments, including mergers and acquisitions, corporate restructurings, sales improvement, overhead reduction, business process re-engineering, and corporate governance projects across a wide range of industries.

“I worked a lot in financial services,” he says. “I also did projects in aluminium and copper smelting, consumer goods industries, an agri-business in New Zealand as well as other industries.” This breadth of experience across different sectors became a key factor in Gardell’s later success as Cevian prizes the ability to take things from one industry and apply them to another

Gardell continues, “Then I worked in consultancy with a lot of the larger private equity houses in Scandinavia. That was when I came across Lars. Lars was at Nordic Capital at the time and we worked together on quite a few different investment opportunities. And then I was invited to become a Partner at Nordic Capital,” he says succinctly.

Shortly afterwards Gardell received an offer from two wealthy Swedes who owned 28% of a listed Swedish company called Custos. Custos itself owned passive stakes in several quoted companies and the owners wanted to release some of the under-appreciated value in them. “I was interested in applying a private equity approach within public markets,” says Gardell, “and I hadn’t seen anyone else do that at the time (1996).” What was particularly attractive to Gardell as the new CEO of Custos was that he was given an open mandate to pursue the strategy and develop the business. In looking for a CIO for Custos, Gardell recalled that Förberg had the creativity and good judgement he was looking for, and so brought him on board. They have worked in tandem ever since.

Cevian

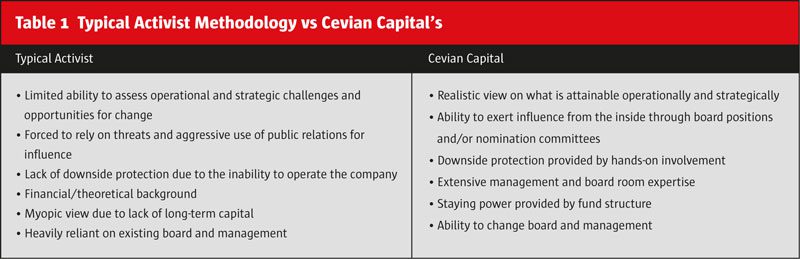

Cevian Capital itself was founded in 2002. The founders describe Cevian Capital as an operational activist fund, which they see as differentiated from the mass of activist funds. The contrast is summed up in Table 1.

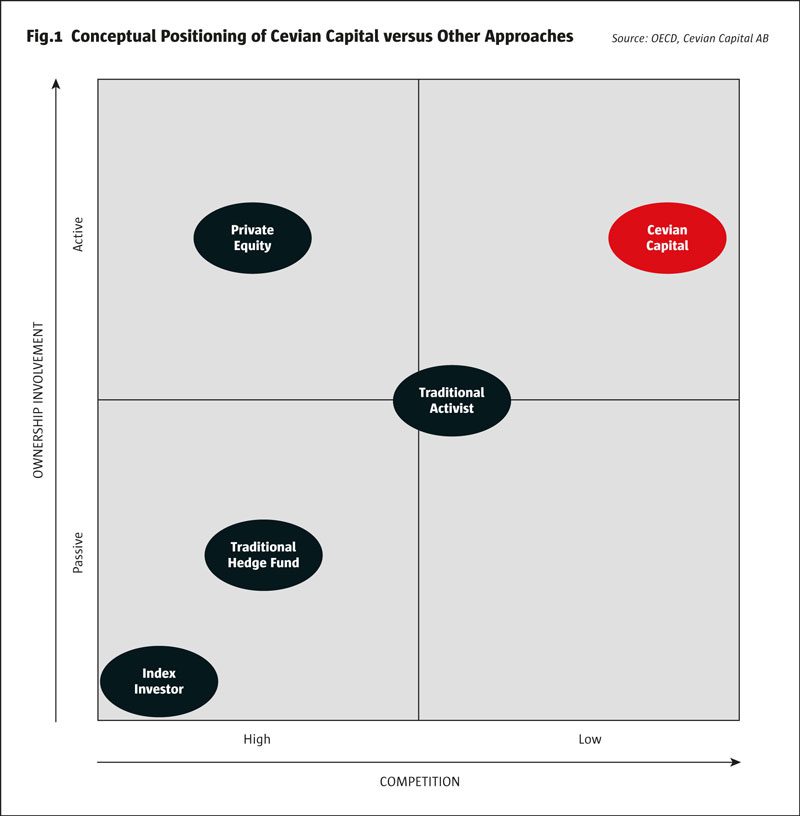

In implementation the approach gives Cevian several advantages over some other alternative strategies: there is less competition (and this is important given the amount of capital in activist strategies). There is no necessity of paying a premium for control, so prices paid may be lower; and there is a higher degree of influence and control in this activist approach. The conceptual positioning of Cevian is given in Figure 1.

Cevian invests in publicly listed companies in Northern Europe, having focussed historically on the Nordic region. Substantial minority ownership positions are taken in a limited number of undervalued companies, where value can be created through operational, hands-on activism. Whilst there may be 8 to 12 positions, typically only five companies make up to 80%-plus of the portfolio, enabling a very high level of focus and engagement. This corresponds to the number of companies that Cevian’s principals think they can engage with at any one time. Gardell comments, “Our ownership approach is to be there for the long term as an active owner, and we take concentrated positions. So we are not short-term traders in companies, but we have a long-term bottom-up approach.” The portfolio tends to be unlevered. The fund is not hedged at the portfolio or stock level.

“We are not looking for bad companies. We are looking for neglectedcompanies or misunderstood companies in out-of-favour industries,” Förberg explains. “So, many of the companies we invest in have an excellent market position and the starting platform is relatively good. This partly explains how they can run such a concentrated portfolio: the targeted companies are thought to have limited downsides. From the analysis they carry out, Cevian estimates that even in the worst circumstances they should not lose more than 20% on a holding. As they have had only one loser out of 18 positions taken in Custos and Cevian I this has not been extensively tested. The aim is for the value of the holding to be capable of being doubled over 3 years. The 5:1 ratio of upside to downside is more heavily skewed to the upside than you would see in most equity strategies including long only and equity hedge strategies.

Cevian Capital undertakes a systematic screening of its universe to identify potential targets that are deemed to be undervalued, and simultaneously offer an opportunity for Cevian to enhance their value through operational activism. At a recent offsite the team estimated that they had 25 potential targets in the pipeline.

Gardell states emphatically “Before we move ahead with an investment, we must have a value enhancement plan that includes all four areas of enhancement (see Table 2). We much prefer a rich plan, with many elements, than an approach based on one key idea that is effectively an all or nothing bet. Also we must be confident that we will be able to execute at least part of the plan on a timely basis.” The first comment is an element that feeds into the control of downside risk per investment, whilst the second timing issue is a key part of attaining a high IRR.

The analytical effort at Cevian is broad and deep. “Before we invest we will often spend 6-7 months working on a company. The ability to dedicate this amount of time to a single investment is a luxury of a concentrated portfolio and sizeable capital base. We think it is particularly important for larger companies, which are normally extremely complex and consequently often misunderstood” says Gardell. “A lot of benchmarking is involved. Then we will frequently bring in outside consultants, like Arthur D Little, to get another perspective on it.” The investment team (currently comprising 10 professionals) will conduct in-depth interviews with competitors and suppliers as well as customers. They will meet divisional heads and talk to executive directors. They will visit the company’s locations of business, whether they are plants or shops or warehouses. “We want to understand what the company has been through, and what initiatives the company has taken itself,” he says. All this is done before a share is bought. “By turning up everywhere (in a sector), it is not possible to guess who we are targeting,” says Förberg.

He continues: “A key question is ‘What is the margin potential?’ We are looking to see where we can add revenues. We are looking to increase the operating margin and return on capital. So we have to look at companies that are in a change process or where we can start the change process. Some investors look for a catalyst in their investments – in our style of investment we are the catalyst.”

An example is the Cevian investment in Swedish industrial icon Volvo. It was trading on an EV/sales ratio of 45%. Gardell says “it didn’t make sense – this company could be on an operating margin of greater than 10% on a sustainable basis. If you get to a margin of 10-12% and you are paying 45% of sales then (looking ahead) you are paying a multiple of 4-5x operating earnings. Looking with a change perspective that was cheap, it was trading in the market at the time on a multiple of current earnings which wasn’t cheap. If you are going to double the value of your investment you have to think beyond financial restructuring, you have to think of operational change.”

Often this requires an unusual conceptualisation of the industry. This is one reason why Cevian staff are all generalists. “If you are too much of an industry specialist you creep inside the box,” states Förberg with certainty. “We need a fresh take on an industry or company. Take the example of Metso (an investment in Cevian Capital I), the mining equipment company. When we looked at it, it was close to default after a major acquisition. After three years of profit warnings it had lost the confidence of the analysts following the company – they were all sellers. We took a completely different view from the market. We realised that Metso would benefit from the China effect, and that the analysts were completely off the mark. It has increased four-fold since 2005. But such ‘thinking outside the box’ is unusual and hard.”

Lindex as an example of the process

A good example was Cevian’s involvement in Swedish clothing retailer Lindex. Cevian started the process with the whole team sitting round a table to discuss the company. They then looked at a couple of issues, including the key cost drivers, and how to schedule working hours within the store to match the pattern of traffic through the day. This work was done not by sitting in the office but by visiting dozens of stores, and talking to store managers about traffic and the new IT system that was introduced and seemingly failing. They also talked to people that used to work at Lindex. These aspects of Lindex’s were then compared to the ‘best in class’, Hennes & Mauritz (H&M).

“We had looked at Lindex a number of times before we got involved and bought shares. That is not unusual for us,” says joint Managing Partner Gardell. For Lindex the 4.5% margin was a mixture of an okay margin in Scandinavia and a loss-making business in the German stores operation that was 10% of sales. So Germany was seen as the key, and the question was ‘could Germany be fixed?’ Other issues were costs (costs had increased for 7 years straight), merchandising more effectively to hit the target customers, and recapitalising the company.

Cevian put together a case team – the group of two, three or four dig deep into the company. Their analysis gave three scenarios for the German operations – continue as is, improve it, or close it down (the worst case scenario). In looking at what would happen if the German stores were closed down it was clear that the leases on the stores were the biggest issue, followed by redundancy costs. The leases were under water, making closing stores expensive.

Gardell takes up the story: “We had to get deeply into the rental lease market in Germany to understand the implications in full: we talked to companies that had gone through store closure programmes there to understand the dynamics, and the costs. We engaged a German real estate expert to fully comprehend the legal aspects. So we looked at the normal market length and cost of leases. We ultimately determined that though the cost of closing stores was high, the pay-back period was very short – only 11/2 to 2 years. So the worst case scenario of closing the German operations entirely would add value to Lindex. We decided to go ahead, and bought a block of stock – 10% in one go. This made us the largest shareholder.”

Cevian then started their change programme by enhancing the composition of the board. In January 2004, three months after Cevian’s investment, Gardell joined the board and was joined by an experienced executive with whom Gardell and Förberg had previously worked. Three long-standing board members stepped down. Later that year, the company was hit with supply problems, and profits suffered. Lindex’s long-standing CEO was let go, and a senior executive was brought in from H&M (he was formerly head of Sweden and ladies wear).

Förberg says “we gave him the opportunity to buy stock options in the company, with a 3-4 year term, consistent with the plan and what he would get in a management buyout. The CEO went to the bank and obtained funding to buy the stock options, as did the whole of the management team, twenty people in all. Christer (Gardell) became Chairman of the company at this point (a year in) and I joined the board as well.

“The company implemented the change programme, both the cost cutting and the revenue enhancement. The company closed down the unprofitable stores in Germany, and subsequently added profitable stores in the Czech Republic and the Baltic states. A new store format was developed which allowed Lindex to enter smaller cities in the Nordic markets. So it ultimately started adding stores in its legacy markets at the rate of 25 stores a year.”

In time, about 6 or 7 executives came in from H&M at divisional level, they too being incentivised with options. According to the joint Managing Partners of Cevian, while a cost-cutting programme may have an impact in a year, revenue enhancement programmes take longer.

In the case of a retailer like Lindex the revenue enhancement was looking to extend and upgrade merchandise, and so cut the extent of discounting. One objective was to decrease the time to market for hot sales lines, and this required an effective tie-in with the logistics system. So a high priority was to upgrade the logistics system – this also facilitated the new format that was developed.

Lindex was transformed from a ‘no growth’, low-margin business to a growing business with expanding margins. At the time Cevian took their initial stake Lindex wasn’t cheap or expensive on either a P/E or cashflow basis (an operating multiple of 10, and a p/e of 14). However Cevian could see that they could be buying it on a potential P/E of 8. The operating margin was taken from 41/2% to the current 14% by both expansionary measures and cost-cutting measures.

It is very striking that the 3-year time frame is similar to the 3-5 year horizon that Warren Buffett applies in buying whole businesses or significant stakes in companies. Buffett expects to enhance the operating characteristics of a business by plugging it into the Berkshire Hathaway family, and also expects to improve the financing of any business he buys.

When the Sage of Omaha first buys a stake it often seems to be that he is not paying a particularly cheap entry price on this or next year’s earnings. It only really becomes clear after a year or two, when the whole market is looking at the earnings potential of what was year three and beyond, that the real worth is evident to all and sundry.

The stock market is very adaptive, and it has taken on board Cevian Capital’s growing reputation. Like TCI, the appearance of Cevian Capital on a stock register provokes a positive reaction. Over the last seven deals, stocks have appreciated an average of 23% over Cevian’s in-price after its holding was made public. But as time goes on, and other factors come in to play, even the halo effect of a Cevian stake can wane. So when buying opportunities arise part way through an enhancement programme, Cevian will commonly add to existing holdings, such as when they increased their stake in Volvo recently by nearly ten percent.

Beyond Scandinavia

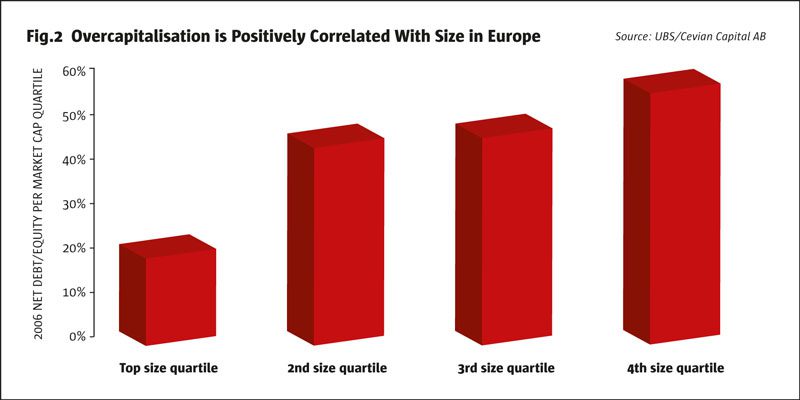

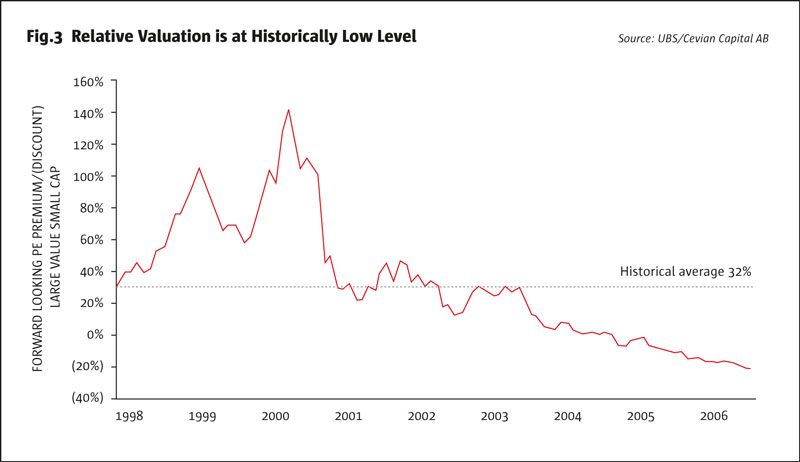

With their first investment vehicle, Custos, Förberg and Gardell concentrated on Swedish investments. In time, for Cevian Capital I, they invested in companies in the Nordic region. With the launch of Cevian Capital II they have broadened their mandate to investments in Northern Europe. Their own analysis suggests that there is a very rich opportunity set in large cap (see Figures 2 and 3), and that the untapped markets of continental Europe are becoming ripe for operational activism.

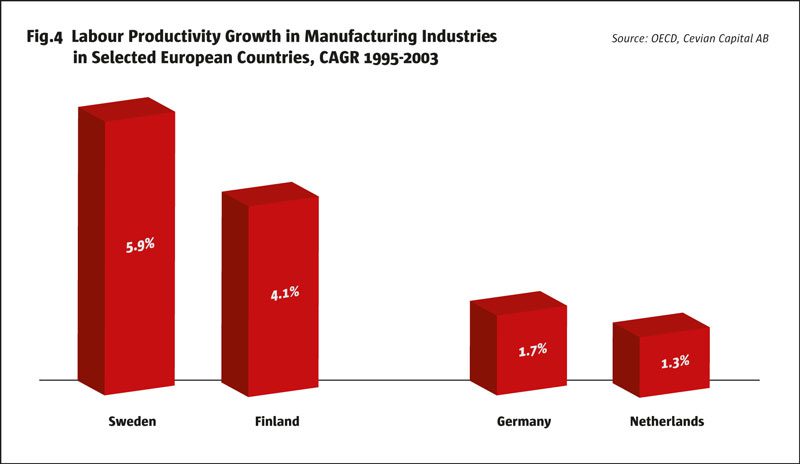

The principals of Cevian Capital suggest that companies there are unexposed to the market of corporate control due to a history of passive ownership. It is estimated that €1.7 trillion, or 15% of total European market cap is locked in suboptimal and value-destroying ownership structures. This is changing as the climate of corporate governance has shifted. The value potential is untapped because of unwieldy corporate structures, operational inefficiencies, overcapitalisation, and entrenched boards and management. The excellent opportunity for operational activists is illustrated in Figure 4 that contrasts labour productivity in Nordic countries with that in Germany and the Netherlands.

Cevian Capital is structurally changing to better fulfil the broadened mandate of the Cevian Capital II fund. A new office has been opened near Zurich at which Förberg is based. In addition, a senior investment professional has been tasked with opening a small London presence. For the Swiss office, Förberg has taken two people with him from Stockholm, and he is in the process of adding analytical staff from different parts of Europe to make the team international. He explains, “We have built a toolbox, and a culture, and style and methodologies. We judged also that it may be difficult to attract non-Scandinavians to live and work in Switzerland. So we have just recruited a Swiss national to come and join us, and we will build from there. What we are looking for in our new recruits is enough analytical and intellectual self -confidence to take a different view from the market. They have to be analytical and creative and, having done the work, they have to draw the right conclusions. We are also looking for people who understand what it takes to change a business – how to move the operating margins of a company from 4 to 10%. Mostly we are looking at people with industrial experience, and looking in different places from the hedge fund industry.” Förberg’s partner Gardell completes the chain of thought: “We have a very thorough recruitment process. In this case we have given Egon Zehnder a very detailed brief.”

Cevian Capital seeks opportunities in a range of industries, including manufacturing (eg. pulp and paper, chemicals conglomerates), and service companies (eg. distribution companies, transportation). Förberg expands, “We carry out a broad opportunity analysis, and will be covering more regions and countries, but our investment strategy and process remain the same and we continue to have 5-6 core investments where we concentrate our time and capital.” According to Förberg, Cevian has had no difficulty identifying high quality potential targets in its newly broadened universe of upper-mid to large-cap companies in Northern Europe.

It is public knowledge that the American billionaire financier Carl Icahn has been an investor in Cevian Capital I and Cevian Capital II. The two Managing Partners of Cevian Capital have known the corporate raider and private equity investor since meeting through a mutual friend in New York in 1998. “He has been a great supporter of ours” says Förberg. “We introduced him to a couple of ideas in Scandinavia at that time, and he made a lot of money from them. He understood and he liked our investment strategy, and we have brought him in when co-investment capital has been needed. We have invited him into four situations as a co-investor in the last 3 or 4 years. We have developed a very good personal and professional relationship with Carl.”

Not like most activists

There are around 55 activist funds in Europe, and Cevian’s returns have been at the very top of the rankings partly because the approach taken is atypical within the strategy. Only 14% of activist funds seek board representation without a proxy contest or confrontation with the existing management/board, according to academic research (Brav, Jiang, Partnoy and Thomas (2007)). So Cevian’s collaborative approach is unusual. Further, the longer holding period of Cevian puts them in the 95th percentile for holding periods of activist funds. This is consistent with Gardell’s comment that most of the other activist funds are run by people with a trader background.

By contrast Förberg says “we are uninterested in where the share prices of our companies are in six months: We are working on what the real value of the company can be in 3 or 4 years time.” The time frame of analysis going out 3-4 years is much more akin to that used by a private equity buyer or Warren Buffet rather than a hedge fund. The ability of Förberg and Gardell to see the potential in their investments in a very different way from other investors is also similar to Buffet’s. Their informed and prepared approach to discussion with incumbent management opens the way up to constructive dialogue, rather than antipathy. It says a lot about the professionalism and human relation skills of Cevian Capital that board members and executives whose positions may be under threat will co-operate with them.

Cevian Capital II is the sole hedge fund invested in by AP1. Icahn has given them capital to manage and has been a co-investor with Cevian. These marks of distinction arise because the returns achieved by Förberg and Gardell have been outstanding – Cevian Capital II was up 31% in the second half of 2006 and nearly 50% in the first three quarters of 2007. Other activists buy assets cheaply. The higher returns of Cevian above buying cheap assets have arisen because they have the ability to conceptualise companies differently – this is creative thinking put into action. And this is the key. Most activists agitate for change from outside and quickly go away. Cevian gets deeply involved in changing companies from the inside – making operational improvement happen as well as enforcing capital discipline and appropriate financial structures. Förberg and Gardell are in the process of working on opportunities outside the Nordic region – it would be surprising if the management of the target companies had come across the pair before. These Northern European company managements are about to discover what it means to have a quality investor on their shareholder list.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical