Following the increase in food prices, index investments in commodity futures have become a target of criticism. They are alleged to share responsibility for the price increases and thus for hunger in the world. Is this actually true or is, if anything, the opposite true?

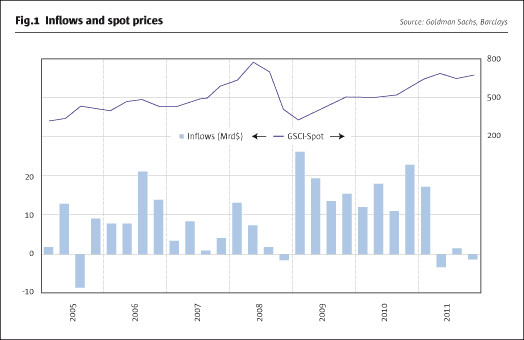

The connection seems straightforward: for years investments have been rising to what are by now hundreds of billions of dollars and food prices have been rising as well. However, what is true for investment assets like gold or stocks doesn’t have to apply to consumables. After all, the commodities themselves are never bought; instead, futures contracts are purchased. Let us look at the relationship more closely. Fig.1 shows the GSCI spot index (as a measure of commodity prices) and the inflows into commodity markets (not the total invested assets, as they reflect price changes 1:1).

In 2006 there were large inflows, but prices went sideways. By contrast they rose strongly in 2007 although inflows declined. Even during the sharp decline in 2008, which resulted in prices falling by two-thirds, no massive outflows were recorded, contrary to what one would expect. Only from 2009 onward can a movement in tandem be discerned which is probably due to a common causal factor, namely the measures taken by central banks. The available numbers ultimately contain no hint that financial investments are actually causing the price increases. Lastly, their magnitude is moderate as well. The funds invested are put into perspective if viewed in the context of the market’s overall size. For instance, in the case of the wheat market, they amount to about 5% of the global annual harvest (whereby, as noted above, there is no delivery of the underlying commodity, as these are continually rolled over futures contracts).

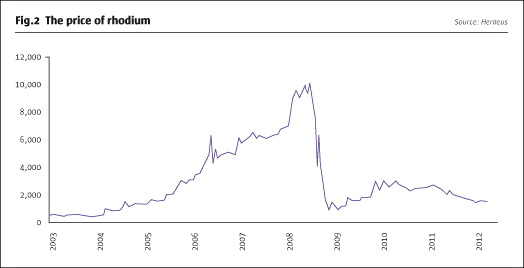

Let us next look at the prices of commodities that index investors largely avoid due to the lack of a liquid futures market. Whether palm oil, manioc, rice, rhodium, cobalt or coal, all these commodities are just as affected by price increases as the ones in which index investors have attained greater importance. Fig.2 shows by way of example the rise and fall of the price of rhodium. It went up 20-fold within a few years! The subsequent decline happened even faster. The speed of the price changes is breathtaking – and all without index investors.

The speed of price changes often plays a big role in the debates over the influence of investments. Fundamental reasons for the price increases of foodstuffs are often acknowledged in this context: population and economic growth, increasing consumption of meat, finite resources, a decline in innovation, rising costs, loss of acreage to bio-fuel production, global money supply growth and so forth. These reasons could explain the price increases, but not the pace and magnitude of their increase, as they have risen threefold within two years. Therefore it is held that a part of the increase must be due to financial investments.

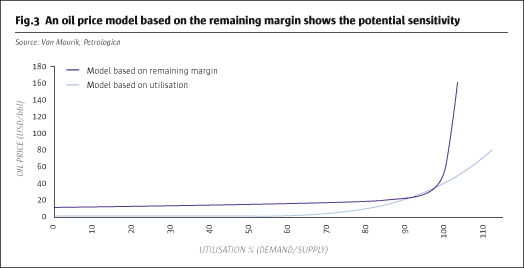

Ultimately, however, in this line of argument the thing to be proved follows from the fact that one cannot name an alternative explanation. Moreover, one has to gloss over the similarly strong increases in the prices of commodities that are not linked to indexes, such as rhodium. After all, there has to be a cause for these as well. However, the cause has been known for a long time: the price elasticity of commodities is far smaller than that of manufactured goods. What would happen if, say, the price of cell phones were to double? Production would be expanded in a very short time by, e.g., running extra shifts. In addition, demand would decrease, as existing cell phones would remain in use for longer. What though is the situation in the context of consumable raw materials? Even a price increase by multiples does not lead to an expansion of production in the short term – it is not possible to simply expand commodity production by increasing the labour effort (if one lets twice as many harvest labourers work in the fields, one will hardly increase the harvest). Rather it is necessary to first engage in the time-consuming process of developing new resources. The elasticity of demand is low as well though, as consumption as a rule can neither be stretched over time nor be quickly reduced through substitution. If, however, quantities can barely be increased, then prices for the remaining available supplies rise strongly. This has been resolved from a theoretical perspective and can be demonstrated here with a price sensitivity model of crude oil from the year 2005 (this is to say from before its strong price increase).

The red line which rises strongly around the 100% mark in Fig.3 demonstrates the effect. In the meantime the model has proved its worth, as crude oil prices have risen strongly. The fundamental backdrop is that production has stagnated since 2005 amid rising demand and in spite of markedly higher prices. Supply is only short by fairly small amounts, but because of that, consumers must pay considerably higher prices. The high price of crude oil is also of importance because it has contributed to higher food prices (fertilizer, bio-fuels, etc.). However, the above illustrated effect – namely that prices increase strongly as soon as demand continues to rise near the marginal limit of the available supply – applies to other commodities as well.

Index investments are executed in the futures markets. Therefore the question arises to what extent futures prices influence cash prices. A short-term effect due to cash traders using futures prices as a guide has to be conceded in individual cases. A prominent example is the rally in cotton prices in February 2008, which had a duration of about one month. However, the influence was thus only temporary. Furthermore, the price subsequently fell especially strongly in an overextended reaction. Overall an increase in prices of consumable commodities cannot become entrenched on account of this guidance effect, as physical demand doesn’t increase when futures contracts are purchased.

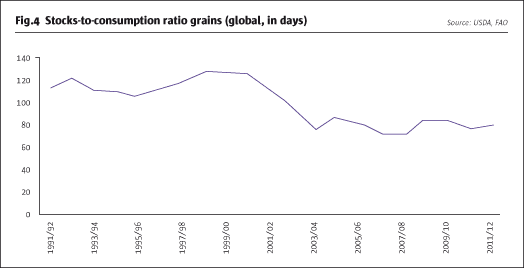

What though about the strong correlation between futures and spot prices that financial market participants are accustomed to? Long index investments are conducted by buying futures, in contracts for future delivery. That pushes the prices of futures contracts up. Arbitrageurs can exploit the widening spread by taking the opposite position of index investors while hedging themselves concurrently in the spot market: they sell the futures contract, but buy the underlying physical commodity concurrently and put it in storage. What is fairly easy to implement in the case of gold or stocks is, however, associated with considerable expenditures in the case of consumable commodities: high storage costs, insurance, transportation costs, feeding costs or depreciation make arbitrage considerably more difficult. This is why there is – in contrast to the financial markets – a large spread between futures prices and spot prices in commodities markets. For instance, the price for delivery in three months can trade up to 10% or 30% above the current spot price, but also 20% below it. At whatever threshold this arbitrage becomes feasible in an individual commodity, it is always associated with an increase in warehouse stocks. Fig.4 therefore shows the warehouse stocks of the most important grain crops (wheat, rice and corn) over the past 20 years.

We can see that during the two most recent bull markets into mid-2008 and in 2010 there were no exceptional changes in warehouse stocks: they fell slightly at times and at times increased slightly. Considering the large number of market participants there may certainly have been additional transfers into storage facilities during this bull market. Overall they are, however, insignificant in view of the minor fluctuations in global warehouse stocks. They are not the driver of prices in these bull markets. Since hoarding (also by governments) has, however, historically repeatedly contributed to regional famines, an eye should be kept on warehouse stocks (for instance in order to intervene by means of regulation). Worldwide storage facilities are less well stocked today than they were about 10 years ago; they should actually be filled up (low warehouse stocks intensify the pace of price increases).

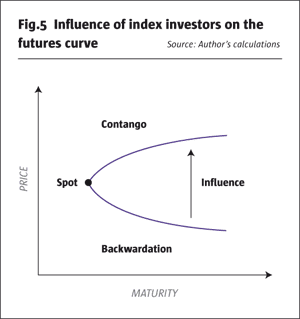

What actually happens with the demand that is generated by futures investments? If warehouse stocks don’t increase, then it doesn’t have an effect on spot prices through arbitrage. However, it does raise prices in the futures market. Thus the additional demand increases the spread between these two prices: index investments lift futures prices relative to spot prices! The following illustration (see Fig.5) visualizes the effect. It shows the change of the futures curve due to index investors schematically: prices of futures are raised from a level below the spot market (backwardation) to one above it (contango).

What actually happens with the demand that is generated by futures investments? If warehouse stocks don’t increase, then it doesn’t have an effect on spot prices through arbitrage. However, it does raise prices in the futures market. Thus the additional demand increases the spread between these two prices: index investments lift futures prices relative to spot prices! The following illustration (see Fig.5) visualizes the effect. It shows the change of the futures curve due to index investors schematically: prices of futures are raised from a level below the spot market (backwardation) to one above it (contango).

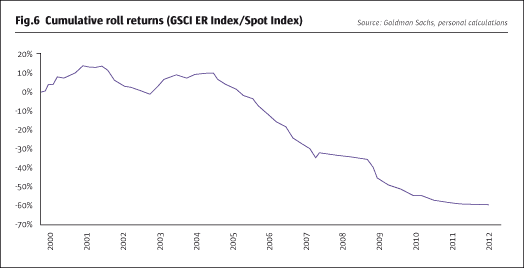

The relationship between futures and spot prices doesn’t follow any fixed rules in the commodities markets. One can therefore not take a direct measurement based on the price level (as, e.g., of the sort “with index investors the futures price will be raised from 5% above spot to 15% above spot”). Statistics can be collated though (and they do establish that futures curves have been altered since index investments have become increasingly prevalent). However, we want to examine the returns here. It is more appropriate to determine the economic effects with their help. Index investors increase the price of a particular futures contract when they buy it, only to lower it again at the time they roll it over, while instead raising the price of the next delivery month. The price of a futures contract has a higher degree of freedom when the delivery date is not yet close. Once the contract matures, it is, however, closely correlated with the spot price. The price increase due to purchases is therefore larger than the price decrease due to sales. Index investors thus influence returns to their own detriment. This effect is provable. Fig.6 shows how the assets of a financial investor without interest returns, the excess return futures index, would have fared relative to the corresponding spot prices (the so-called roll returns).

If futures prices were solely based on expectations as simplified models claim, then returns from futures should be roughly similar to those of spot prices over the long term. In reality they increase, while fluctuating, more than spot prices since the 1970s (the available time series). From 2004 onward, when index investors began to increasingly invest in futures, the picture changes dramatically. The curve declines massively. Futures investments lost about two-thirds of their value relative to spot commodity prices! Even the strong rally in commodity prices could not compensate for these roll-over losses; investors lost money. Index investors have produced these roll losses for themselves due to their sheer mass. Their billions haven’t raised spot prices, but have instead raised the futures curve above spot prices. That becomes noticeable in the altered futures curve and in terms of returns as a loss of the futures index relative to the spot price index. Demand by index investors doesn’t unfold its effects in the spot market, but in increased roll losses!

However, where losses are made, there are also always winners in the futures markets (in contrast to the spot markets). The roll losses of index investors reappear as profits in the accounts of their counterparties that have sold the commodity futures short. Among those are producers. Farmers get higher prices in the futures markets due to index investors. They garner additional roll returns, which are not subject to an offsetting disadvantage for producers. It is a market inefficiency created by the activities of index investors (since their decisions are biased to the long side independent of market assessments). Their roll losses become the profits of farmers.

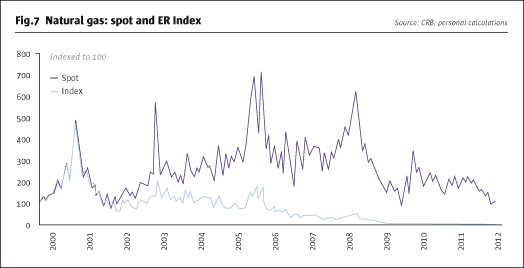

What is largely disregarded in the current debate over prices can be found on the other side of the equation: quantities. Effects on quantities are even more difficult to determine than those on prices: it is hardly possible to quantify by how much smaller harvests would have been if there were no index investments. However, the fundamental principle that higher returns are an incentive for farmers to increase production should hold true. We can take a look at an extreme example from the energy sector: no commodity has had roll losses as high as those seen in natural gas. Fig.7 shows how an investment in natural gas futures has fared compared to spot prices since the year 2000: while the spot market actually rose slightly, an index investor in natural gas lost 98%! Offsetting this loss of almost 3% per month (!) was a respectable roll profit for the hedging producers. This additional roll profit was (among other things) one of the reasons why the so-called “fracking” technique could be developed and financed so successfully in the US. As a result production volumes expanded along with falling prices. Natural gas is without a doubt an extreme example, but it demonstrates the fundamental principle quite well, namely how roll gains on the hedge position can affect production quantities.

With that the causal chain is perfected: the additional demand from index investments ultimately doesn’t affect the spot markets, but leads to strongly altered futures curves on the futures markets and negative roll yields. These conversely become massively higher profits for the hedging producers. As a result production is increased.

We don’t want to overestimate this effect for markets other than natural gas, but it must exist. If there were no longer any index investments, there would be far fewer counterparties for the producers (according to figures released by the CFTC, swap dealers, behind which most often are index investors, in some cases represent the entire counterparty position to producers). The proceeds of producers would shrink, and these losses would have to be borne by someone (consumers? The government with further billions in subsidies?).

There is one more factor to discuss, as there are not only hedging producers, but also hedging processors. They could pass higher prices on to consumers. Strangely enough this factor so far barely plays a role in the debate over the influence of index investments on consumer prices. It has to be present in principle; the question is merely to what extent. How many processors are even affected? We must consider that the structure of market participants in the futures markets is not symmetrical. In an extreme case there could be producers engaged as sellers, but no processors whatsoever as buyers (after all there are other market participants as well, such as speculators). The seeming paradox of an increase in futures prices would arise that benefits producers, but wouldn’t affect processors and thereby consumers. The different extent of participation of producers and processors in the futures markets leads to an asymmetrical impact of price effects.

For the purpose of estimating the actual conditions in the food sector, two facts are relevant: on the one hand, the hedging demand on the part of producers is as a rule higher than that of processors. The reason for this is that producers have already completed their expenditures and thus have price risk, while most processors can pass their costs on and have no reason to hedge them for this purpose. In most cases, producers are furthermore less diversified in terms of the number of products. In markets with a large number of commercial participants this asymmetry of risk leads to an overhang of hedging requirements on the part of selling producers, and hence low futures prices, a phenomenon that is referred to as ‘normal backwardation’. (This was the reason why roll returns were positive for investors until 2004.) Due to this risk asymmetry, market efficiency is absent at normal backwardation as well.

Ultimately index investors of all market participants are the ones balancing the resulting disadvantage of producers out. They reverse the phenomenon, because they themselves are acting asymmetrically. Now it is no longer the hedgers, but investors that pay a premium (for participating in the commodity markets). The risk asymmetry due to higher hedging requirements on the part of producers, however, means essentiallythat the quantities hedged are larger on the part of producers than on the part of processors. Therefore more producers than processors are affected by rising prices in the futures markets. On the other hand, the index investors themselves now contribute to higher participation by producers rather than processors in the futures markets, as they raise the roll profits of producers considerably. Producers are offered an additional incentive to hedge. Concurrently the higher roll losses make hedging less attractive for processors, so they pull back. Finally there is the question of who is behind the hedging processors. There are barely any indications that buyers in the underdeveloped regions of the third world are active as hedgers in large numbers in the US futures markets. Regarding the influence of futures prices one can all in all conclude: far more US farmers are hedging than grain buyers from the third world.

The debate has so far been focused on prices. We have additionally examined the influence of index investments on quantities. In the course of this we have come across a hitherto little-noticed effect in the context of roll returns. With it, index investors help to alleviate hunger. By their sheer mass they influence the futures curve to their own detriment and generate roll losses in the process. These are mirrored by markedly improved roll profits on the part of hedging producers. These profits represent an incentive to increase production, without there being an offsetting disadvantage in terms of consumer prices. Index investors are paying a continuous subsidy to farmers, not out of charity, but due to the unintended side effects of their investments.

Dimitri Speck is chief developer of the trading strategies for the asset manager Staedel Hanseatic. He has specialized in commodities and is responsible for the Stay-C fund that won this year’s award as best European UCITS commodity fund. Speck has written a book about the gold market, is publisher of the website www.seasonalcharts.com and holds a patent for an iterative financial market.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 83

How Do Commodity Futures Affect Hunger?

Are they responsible for price increases?

DIMITRI SPECK, STAEDEL HANSEATIC

Originally published in the February 2013 issue