In our experience many (or at least most) hedge fund managers are excellent at managing their portfolios but are often much less proficient at setting the best price level for their services. Fee structuring may range from a more aggressive “what the market can bear” approach to a “marginal cost pricing” approach. In the case of the latter, once a firm reaches its break-even point on a perceived sustainable management fee income level, any and all new investment products could be sold at marginal cost levels, which in practice is very close to zero.

From a basic macro-economic perspective, the “what the market can bear” approach is the most rational approach, at least in the short-term. Managers whose investment skill set are in high demand can set their price level higher than other managers. Without naming names, there are examples of 3% management fees and/or 25% performance fees. This approach is defendable when the manager can show consistent alpha even after these fees are applied. However, few (if any) managers consistently do so year after year. The risk in a weak(er) year for the manager is that investors will more easily turn on the manager and take “revenge” for having paid such exceptional fees.

What fee structure results in the lowest actual fees paid really depends on the nature of the returns.

Taco Sieburgh Sjoerdsma, Founder, PH7 Hedge Fund Consultants

Another example of “what the market can bear” approach is where the investment manager pursues an investment strategy, or invests in an asset class, not easily accessible to investors for operational or other reasons. For example, at Sturgeon Capital we set up an Iran focused investment fund, where the stock market looked very attractive but was highly difficult for investors to enter in a sanction-compliant manner. In this situation hedge fund-type fees were charged for what was essentially a long-only equity product.

The “marginal cost pricing” approach is for most hedge fund managers a sub-optimal approach. Its basic premise that lower fees will generate higher demand would make economic sense if the manager is offering a commodity product. Even in the case of ETF products and/or long-only government bond funds there are enough differentiators as to how the product is structured, sold and serviced. However, hedge funds are seldom anything close to a commodity product, and each manager tends to be able to differentiate its investment universe, strategy, approach from the next manager. Hedge fund investors firstly focus on all these aspects, then on a potential risk/return pay-off thereof, then on a range of other factors (for example operational due diligence, investor disclosure), and only then on the fees. Setting fees at an exceptionally low-price level does not simply create extra demand for most hedge fund products.

In our experience many hedge fund managers seem to fail to properly grasp the distribution costs, in particular third-party marketing fees and/or wealth manager retrocessions. A typical, reputable third-party marketer will take 20% of the management and performance fees, plus often a retainer, while many wealth managers/distribution platforms take a much larger share of the management fee, but no performance fee share. If a hedge fund manager sets its fees at a low price point it will become virtually impossible to attract external capital raising/distribution support. Thus, fees set too low can result in less capital accretion, a total expense ratio which does not come down, and an inability to (re)-invest in the investment management business, possibly to the detriment of the fund’s investors.

Although it would be logical to assume that lower fees should result in higher net returns, as we showed in a previous study (published in The Hedge Fund Journal back in 2006), for hedge funds there is no correlation between fee levels and net returns. For example, in this study it was shown that 45 equity long/short funds charging 2% and 20% generated over 3 years on an annual basis 1.7% higher returns than 286 funds charging 1% and 20%.

Other than lower fees not generating higher demand, what many starting managers fail to understand, and established managers have often learned the hard way, is that many large institutional investors will try to negotiate lower fees, no matter what the headline number is. Particularly large funds of hedge funds are in a competitive market environment and consistently lower fees (on their own fees) may make a difference to their own investors.

In general, the level of hedge fund fees should not preclude engaging with the end investor in a discussion about the manager’s investment process. If at an early stage the fee level is raised (often by a more junior fund analyst), a simple reply that these can be negotiable should move along the real discussion about the manager’s investment abilities. If this seems to be a deal breaker from the outset, in our experience this tends to be used as an excuse not to engage i.e. the investor was basically not interested.

For an investment manager it is very important to remember that fees are always negotiated downwards, never upwards, and when negotiating fees the investment manager should be mindful of regulatory obligations (for example treating customers fairly), contractual obligations, disclosure obligations and not least, we would argue, moral obligations.

At the same time, and not taking anything away from the above, it should also be remembered that the hedge fund fee structure consists of at least five elements, namely:

- management fee level

- performance fee level

- payment frequency of management and performance fees

- hurdle rates for performance fees (if any)

- high water mark/performance fee level resets (if any)

In addition, an investment manager may charge sales and redemption fees, while the director and manager also can control other fund charges (which also may be capped).

In short, it is not a simple matter of whether to charge 1.5% and 20% or 2% and 20%, but there is an infinite number of variations of fees.

Moreover, the total fees paid by an investor will, given these various fee structures, vary widely depending on what actual gross returns are generated by a manager. To illustrate this, take the example of an equity long/short manager with a 2% (monthly) and 20% (annual) fee structure with no hurdle and no resets, who engages with a large institutional investor wishing to make an allocation substantially in excess of minimum contribution levels. In addition, the investor is willing to have the funds locked-up for a longer period than in the prospectus. In short, the fund terms (i.e. liquidity, minimum amount) may be sufficiently different from other investors’ terms to allow an alternative fee structure, with all appropriate disclosures being made.

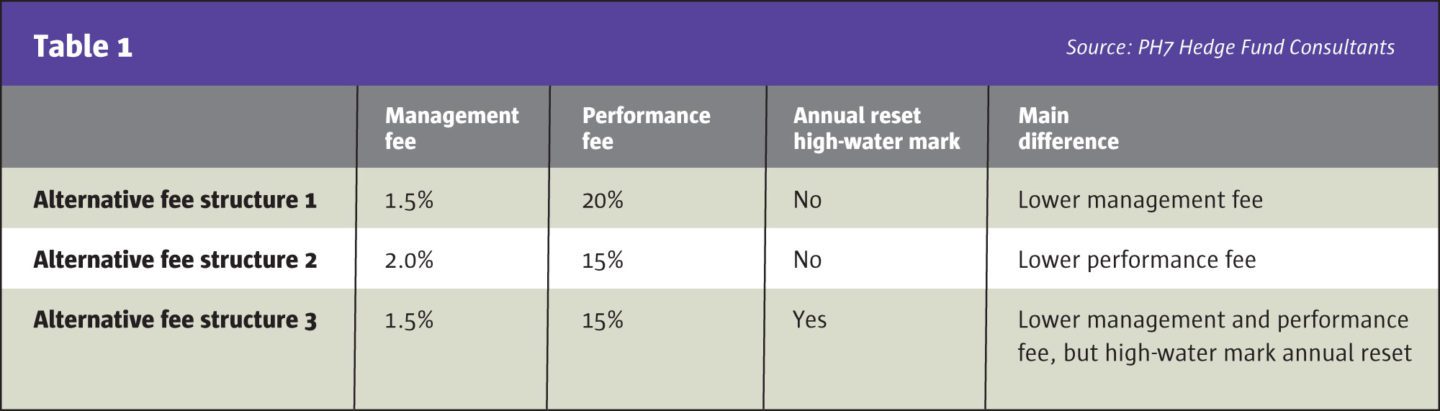

For example, the investment manager may propose three alternative fee structures as per Table 1.

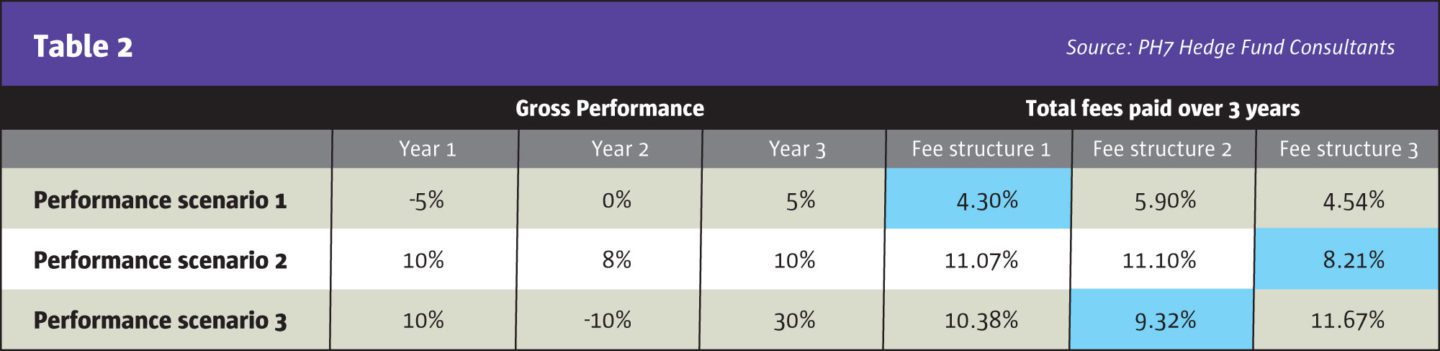

What fee structure results in the lowest actual fees paid really depends on the nature of the returns. In Table 2, we give three different return scenarios over three years. What we like to highlight is the fact that which alternative fee structure generates the lowest and highest fee paid can never be known beforehand. We highlight in blue the cheapest fee structure under different performance scenarios.

What we believe is of greatest importance to hedge fund managers is to engage in a constructive dialogue with any investor seeking an alternative fee arrangement. The key is to listen and try to understand the investor’s particular focus. Fees should be a clear multi-factor negotiation (of which we only highlight three) so there is surely a possibility of a win-win outcome.

The above examples should be taken into consideration when institutional investors ask for “most favoured nation” status. As an investment manager can vary different aspects of the fee structure, and here we only used three factors, the objective is to avoid changing those parts of the fee structure that are specified in the “most favoured nation” provisions.

One fee structure aspect which investors seldom focus on is the frequency of performance fee payments. Traditionally the performance fee is set on an annual basis and/or paid after an annual fund audit. In the case of the latter, with independent pricing of assets and a strong administrator firm, the chances of wrongful calculations of performance fees should diminish sharply. However, the setting of an annual performance fee may also create wrongful incentives for hedge fund managers. For example, either to “lock in” the performance for the year early, i.e. we did well year-to-date in early December, so let’s go to cash, de-risk, have a nice holiday and pocket our performance fee. In this situation potential additional performance is left off the table. Alternatively, and much worse, hedge fund managers may invest in illiquid stock and pump up their share prices just before the final performance date cut-off. There have been some well publicized scandals in this regard.

To avoid having to deal with wrongful incentives is one of the reasons we believe investment managers should propose to their investors more frequent performance fee payments. We also note that the legal language in offering memoranda quite often needs to be carefully re-read several times, referencing between various clauses, before it becomes even clear what the frequency is.

As to hurdle rates, or not, there is a wide range of views and preference on these. In essence, the manager only gets a performance fee if she outperforms the benchmark. However, investors should focus on both returns and risk, (mainly) expressed as volatility. A simple hurdle rate does not make a distinction as to the risk factor. Over shorter time frames, where volatility has a greater impact on the final outcome, this would be less appropriate, but for fixed, longer-term investments, such as private equity funds, this becomes more appropriate.

Finally, in setting hedge fund fees investment managers should use great caution when trying to interpret reports about the overall direction of fee levels, when setting their own fee levels for the following reasons.

Firstly, whereas headline fees are widely available, negotiated fees are not. There simply is no actual data available. We note that in the past we have seen anecdotal reporting of headline fees declining, while actual more in-depth like-for-like studies for a strategy showed fees increasing, i.e. there is a lot of noise, but little observable fact.

Secondly, hedge funds are not a homogeneous product and the overall level of fees should be compared with the specific focus of the manager. Put simply, credit hedge fund fees have (probably) declined for the simple reason that any alpha in a low-interest environment has also declined. In a high return environment for an asset class, for example equities, obviously the investment manager can, fairly or unfairly, charge higher fees than in a low return environment.

Thirdly, the hedge fund industry has also become exposed to a certain level of “retailisation” – for example selling a hedge fund strategy through a UCITS structure or stock-exchange listed vehicles to allow small investors access, as opposed to the historic focus on UNHWs and institutions. In many cases, the “hedge” in hedge fund management becomes significantly less, and funds are more compared to lower (management) fee long-only products. What is conveniently forgotten in these types of reports are the upfront sales fee which are then often charged.

In conclusion, there is nothing simple about hedge fund fee structuring. For both established and emerging managers we believe fee structures, which are a key factor for a manager’s profitability, deserve much more attention and thought than is often the case. Internal feedback from investor relations colleagues, whose incentive is to sell more rather than less, may generate sub-optimal solutions.

As a hedge fund consultant and as a former hedge fund manager, we recommend managers take some additional time and external advice on fee structuring and/or periodic fee reviews, as this is well worth the time and money in terms of either future ability to generate greater assets under management (and reduce a fund’s total expense ratio) and/or to generate greater revenues for the manager, and so enable the manager to reinvest in the business to the benefit of investors.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 150

How to Set and Negotiate Hedge Fund Fees

Consult, engage and listen for a win-win solution

Taco Sieburgh Sjoerdsma, CFA, Founder, PH7 Hedge Fund Consultants

Originally published in the August | September 2020 issue