For the past eight years the US dollar (USD) has been on an upward trend, rising substantially against most of its peers. Support came from three sources:

1) An improving US fiscal situation from 2010 to 2016.

2) Substantially tighter monetary policy since 2016.

3) Stronger US growth than in Europe and Japan, especially in 2011-13, and since 2017.

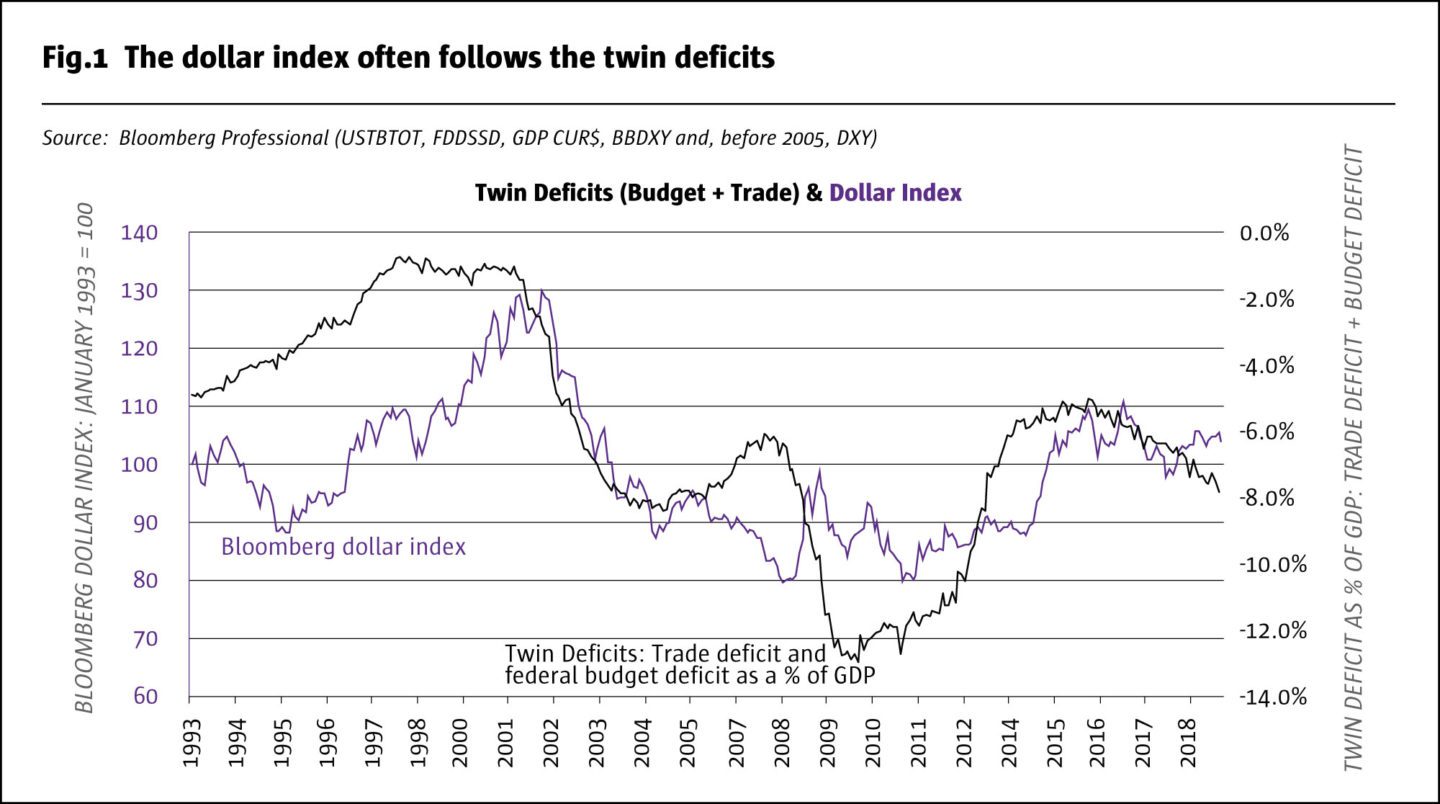

The first of the three sources of support for the dollar was undercut in 2017 when the US budget deficit expanded from 2.2% of GDP in 2016 to 4.7% by mid-2019. Additionally, despite recent protectionist measures, the US trade deficit has expanded, rising from 2.5% to 3.0% of GDP. This has taken the so-called “twin deficits” from 4.7% to 7.7% of GDP.

For the past three decades smaller twin deficits have usually been followed by a stronger USD – often with a lag of 1 to 2 years. Meanwhile, expanding deficits have often been followed by a much weaker USD, often with a much shorter lag (Fig.1).

This time around, USD has resisted a major selloff largely because of Fed tightening and the boost to growth from the tax cuts that took effect in 2018.

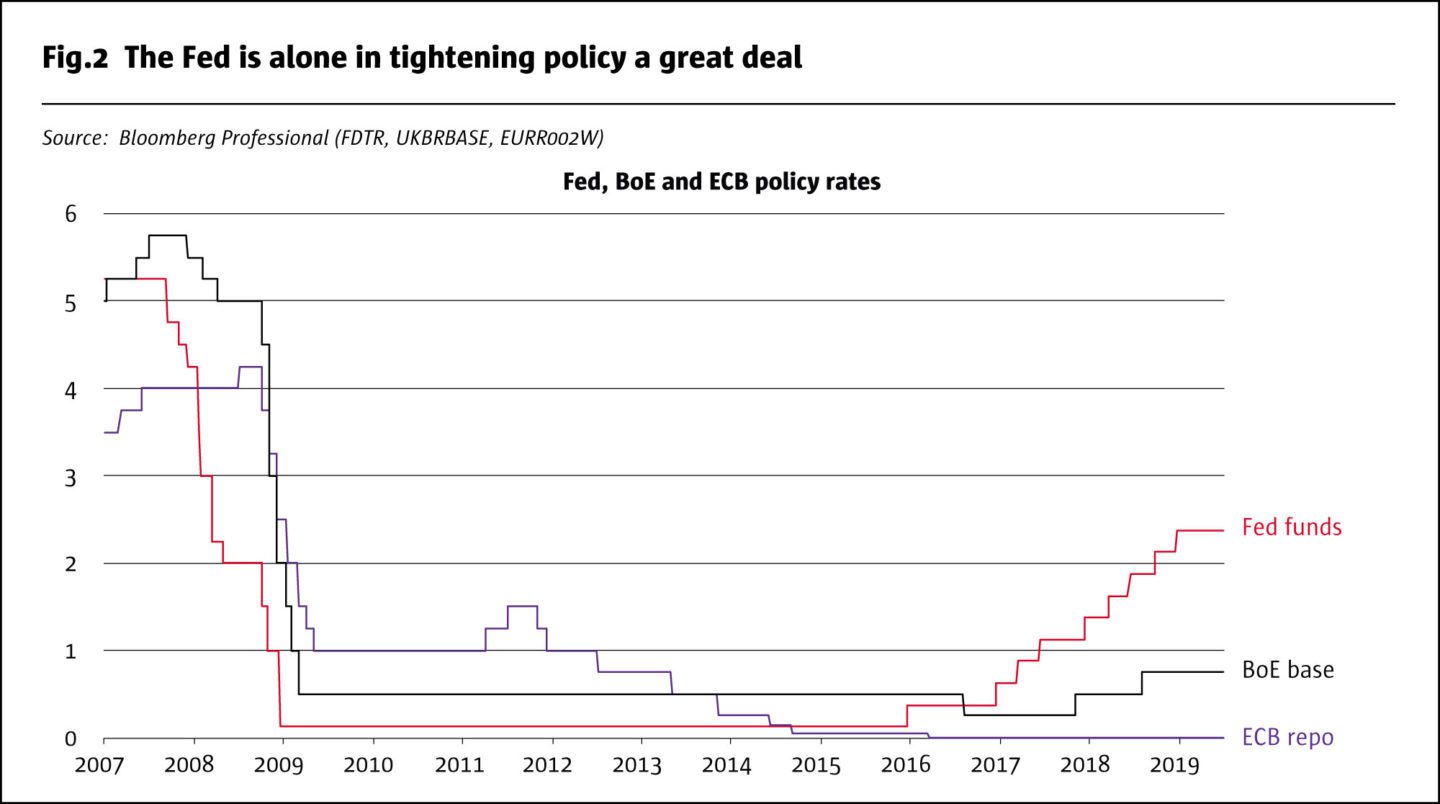

The Fed hiked rates four times in 2018, bringing the total number of increases to nine in the current cycle that began at the end of 2015. No other central bank has raised rates anywhere near as often. While the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England have dipped their toes in rate hikes, most other central banks including the European Central Bank (ECB), the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) have had easy monetary policy (Fig.2). Some central banks such as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) have been actively easing monetary policy.

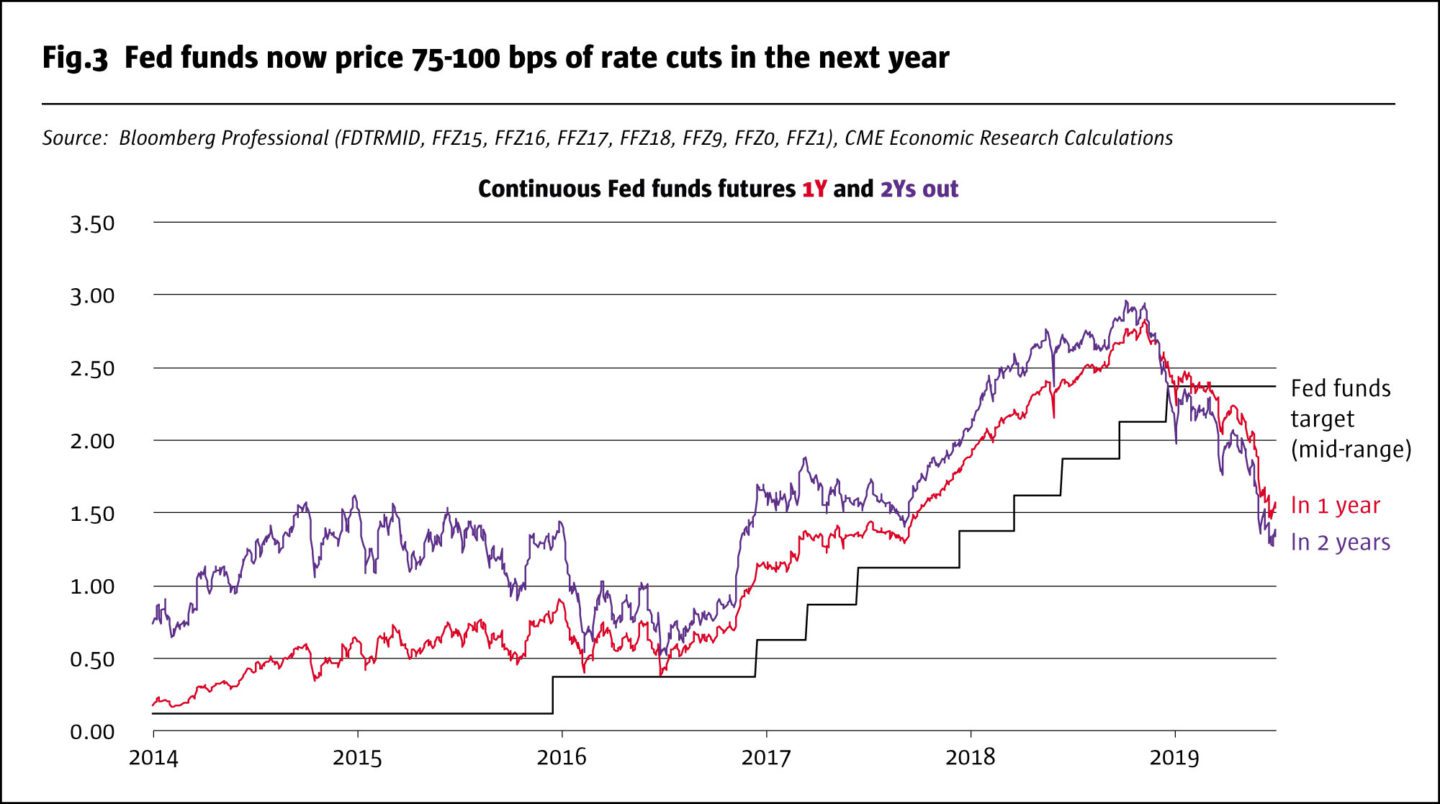

The market is pricing that the Fed will cut interest rates up to four times over the next year (Fig.3) but, so far, the Fed itself hasn’t committed to such a drastic policy action, only opening the door to a possible rate cut. Nevertheless, US monetary policy probably will no longer be a source of support for the USD in the year ahead, unless there is a dramatic change in rate expectations.

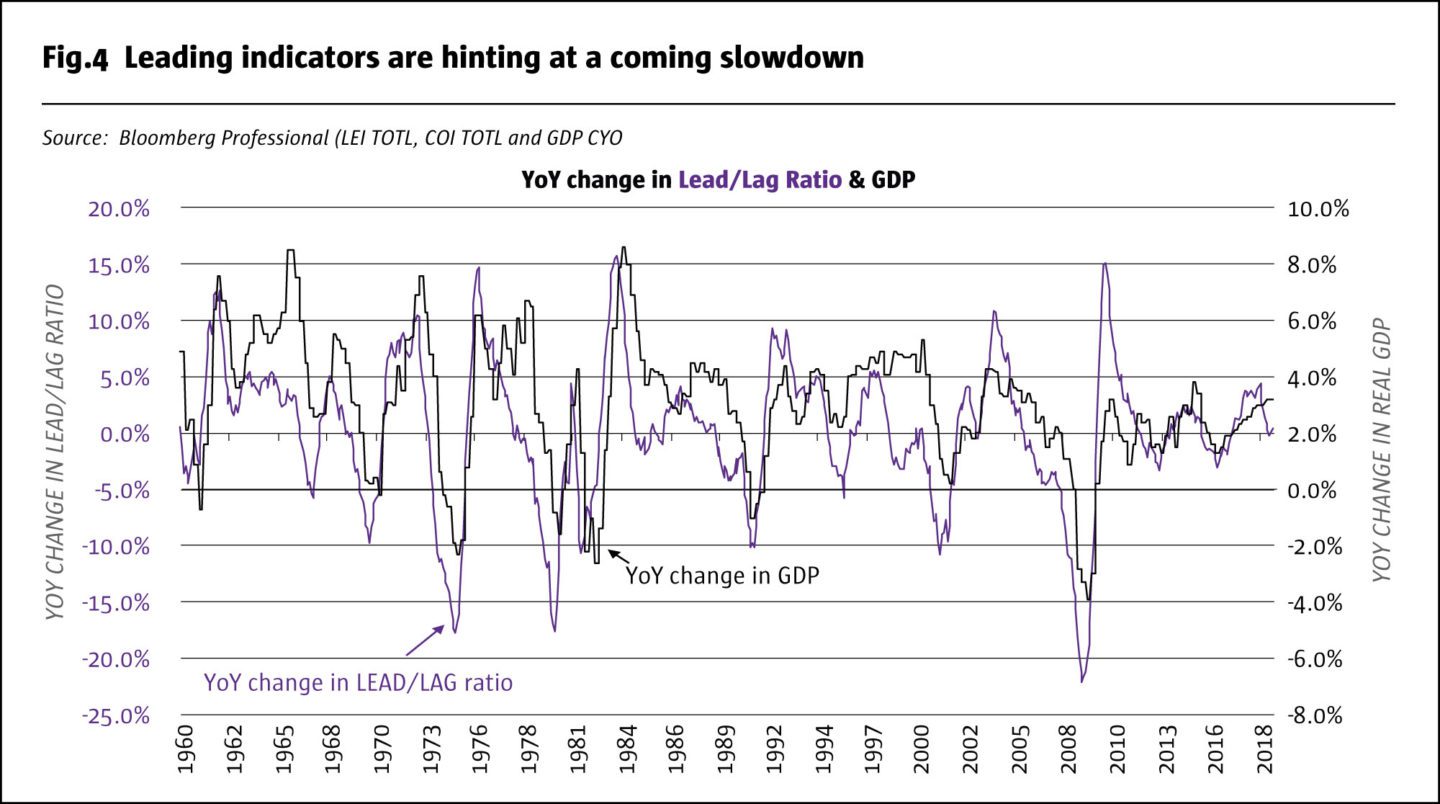

Further, fear of a slowdown in US growth is a large part of the reason why fixed income markets have come to price such a dramatic change in Fed policy. So far, the evidence of an economic slowdown has been mixed, but the ratios of US leading-to-coincident and leading-to-lagging indicators have been pointing to a moderation in the pace of US growth (Fig.4). If the US expansion slows, it will go a long way towards closing the growth gap between the US and the already struggling economies in Europe, and Japan.

Finally, what should be of greatest concern to anyone long USD is the possibility that the Fed might keep rates too high for too long that results in an economic downturn that subsequently requires the return to near-zero rates. During recessions, the US budget deficit expands by about 4% of GDP on average – although the trade deficit usually shrinks a bit. Under that circumstance, USD would be faced with rates stuck near zero, huge twin deficits (mainly from the budget side) and no growth gap with the rest of the world.

So, if USD suffers another decade-long bear market in the 2020s, like it did from 2002 until 2011, who benefits? Which currencies would be most likely to go higher?

Here is our ranking of the likely “beneficiaries” of any dollar weakness (and we put beneficiaries in quotes because a stronger currency isn’t necessarily good for the economy).

- The British Pound (GBP): GBP is undervalued against the dollar and the euro mainly because of the uncertainty that surrounds Brexit. Traders fear a worst-case scenario: the pound collapses on or around October 31, 2019, if Britain has a no-deal exit from the EU. This is possible but even under the worst-case scenario, one must remember that in the long term there is no such thing as a no-deal exit. If Britain leaves without a deal, its very likely that in subsequent years there will be a deal that will look a great deal like what Theresa May negotiated and the pound will rebound strongly. Moreover, it is still possible that Britain will leave with a deal, in which case the pound will probably soar in value versus both USD and the euro. It’s also possible that the UK will extend the negotiating period once again and perhaps even hold a second referendum in 2020. This would be less pound-supportive in the short term but could produce a big rally depending upon the ultimate outcome of the extension or a second referendum.

- The Swiss Franc (CHF): the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has done everything imaginable to prevent CHF from soaring. It dramatically expanded its balance sheet by selling CHF to buy foreign (largely eurozone) assets. It even has deposit rates at -1% to discourage foreigners from buying and holding the Swiss currency. The problem is: if CHF starts soaring again as USD weakens, what exactly will the SNB do about it? Put the deposit rate a -2%, or even -5%? Negative deposit rates are a tax on the domestic banking system as well as on foreign investors who hold such deposits and Swiss banks are hardly stellar performers these days. When it comes to monetary easing and intentionally capping of the value of its currency, Switzerland may be nearing the end of its rope. Hence a weak USD could send CHF soaring whether the SNB likes it or not.

- The Japanese Yen (JPY): the Bank of Japan has a fundamentally similar story to the SNB – only the details differ. BOJ also has negative interest rates and it also intentionally weakened its currency during the middle of the last decade through a massive quantitative easing (QE) program that took its balance sheet to nearly 100% of GDP – more than 2x the ECB’s and nearly 4x the Fed’s relative to the size of their economies. With inflation barely positive and economic growth stalling, Japan doesn’t need a stronger JPY. That said, currency markets don’t give you what you want or need. They give you what they give you.

- The Euro (EUR): with inflation stuck near 1%, a full point below the US and Britain, the eurozone doesn’t need a strong currency much more than Japan but that doesn’t mean that they won’t eventually wind up with one. The ECB has deposit rates at -0.40%, which translates into a 7.5 billion EUR per year tax on banks. Not surprisingly, the banking system is suffering, and credit is surprisingly difficult to obtain despite the extremely low rates. Moreover, the main proponent of negative deposit rates, Mario Draghi, is leaving his post as ECB President after eight years in October and could be replaced by somebody who could, paradoxically, ease monetary conditions by raising rates and removing the negative deposit rate’s tax on banks. Finally, the ECB expanded its balance sheet to over 40% of GDP and is also hitting constrains regarding further QE measures. What could hold back EUR from appreciating versus USD is political dysfunction. With a common currency but no common fiscal policy, Europe can’t even be properly understood to have a sovereign bond market. It essentially has a municipal bond market where countries can default on loans. Additionally, the political system is highly fragmented between different levels government (the nations’ versus the EU) and within the member states’ own political systems. That said, EUR appreciation, no matter how unwelcome, cannot be ruled out.

- The Scandis: The Norwegian krone (NOK) and Swedish Krona (SEK) will most probably follow EUR. They might not do as well as CHF or GBP. Sweden has a real estate bubble to contend with and Norway’s currency varies to some extent with petroleum prices but overall they are likely to do about as well as the euro.

- The Indian Rupee: INR could also be an outperformer. India has a services-oriented economy that continues to grow quickly. Unlike China, it has low debt and unlike Brazil and Russia, it’s a commodity importer. Moreover, it has a significant positive interest rate differential with the rest of the world.

- The Chinese Renminbi: Unlike, GBP, CHF, JPY and even EUR, RMB is not such a great candidate for strength versus USD. During the next decade, China is likely to see negative growth in its working-age population and a slowing of the rural-to-urban transition. It also faces a crushing debt burden. When one looks at RMB from a USD perspective, it does move – usually smoothly— sometimes rising and sometimes falling. But essentially, RMB is closely connected to USD and if USD falls a great deal during the 2020s, it will likely take RMB down with it. Sometimes RMB might underperform, especially if Chinese growth slows a great deal, and otherwise it might outperform, when Chinese growth rebounds.

- Australia and Canada: Both the Aussies and Canadians have loaded up on debt and have real estate bubbles, at least in certain markets. Moreover, both are major exporters of natural resources, much of which is directed towards China. Australia’s currency may be in especially dire shape: its two main exports, iron ore and coal, both have a doubtful future. Iron ore supplies have tripled since 1994 and China buys two-thirds of the global supply, including almost all of Australia’s exports. The reason why China buys so much iron ore is that since China began growing from a very low standard of living, there was very little scrap to recycle from disused automobiles, demolished building etc. Now that many Chinese own cars, that will begin to change, and China’s need for iron ore may begin to wane. When it comes to coal, China is making impressive strides towards cleaner energy, with enormous investments in wind and solar. The combination of slower growth in China plus significantly reduced demand for both coal and iron ore could throttle Australia’s two main exports and lead to the AUD being an even weaker currency than the USD.

Bottom line

- The US dollar could weaken because of bigger deficits, lower rates and slower growth.

- British pound may be undervalued because of Brexit and susceptible to a long-term rally.

- It may be hard for central banks to further devalue Euro, Swiss franc and Yen.

- Among emerging market currencies, the low-debt, not-commodity-dependent Indian rupee may be a winner.

- The Renminbi might follow USD downward.

- Iron ore and coal cast a dark cloud over the future of the Australian dollar.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 142

If US Dollar Weakens, Who Benefits?

The implications

Erik Norland, Senior Economist, CME Group

Originally published in the August 2019 issue