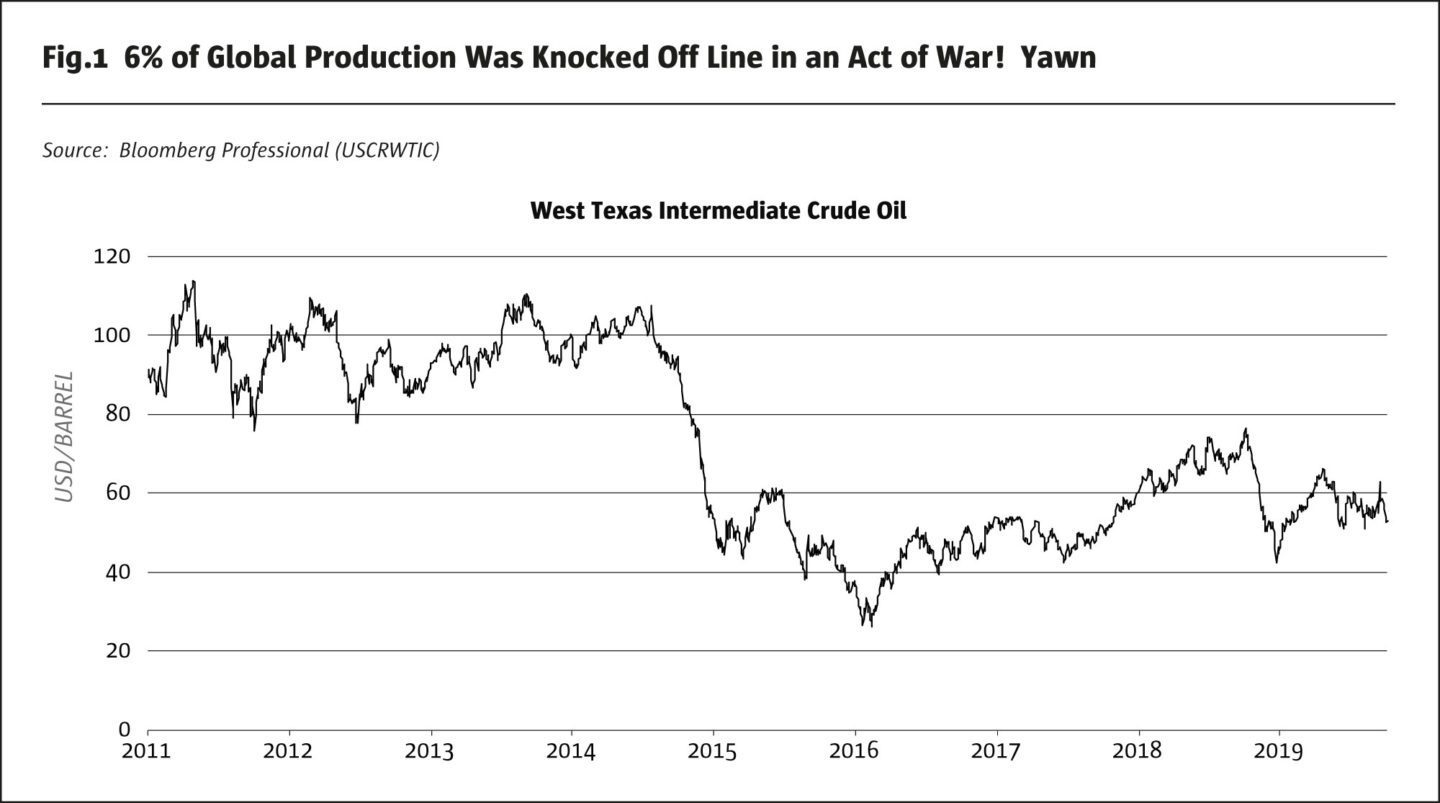

It’s now been three weeks since a drone attacked and knocked out half of Saudi Arabia’s oil production and, if one hadn’t read the news and just casually glanced at the futures and options markets, one would never know that anything had been amiss. Oil prices are smack in the middle of their recent range. The 14% up move on Monday the 16th of September looks like a blip on the long-term charts and the oil market has given up most of those gains.

And why did oil rally only 14%? And why the lack of follow through in subsequent trading sessions? If half of Saudi Arabia’s oil production was knocked out, that’s 6 million barrels per day in lost production, or about 6% of global total production. Past disruptions in oil supply, like the ones that occurred when the Arab Spring protests toppled the government of Libya, produced much bigger reactions. Then a 2-3% drop in global supply, sent prices 15-30% higher. The 1973 Arab Oil Embargo cut global production by about 6% and sent prices 300% higher. The 1979-80 oil shock reduced global supply by about 4% and caused prices to rise by around 200%.

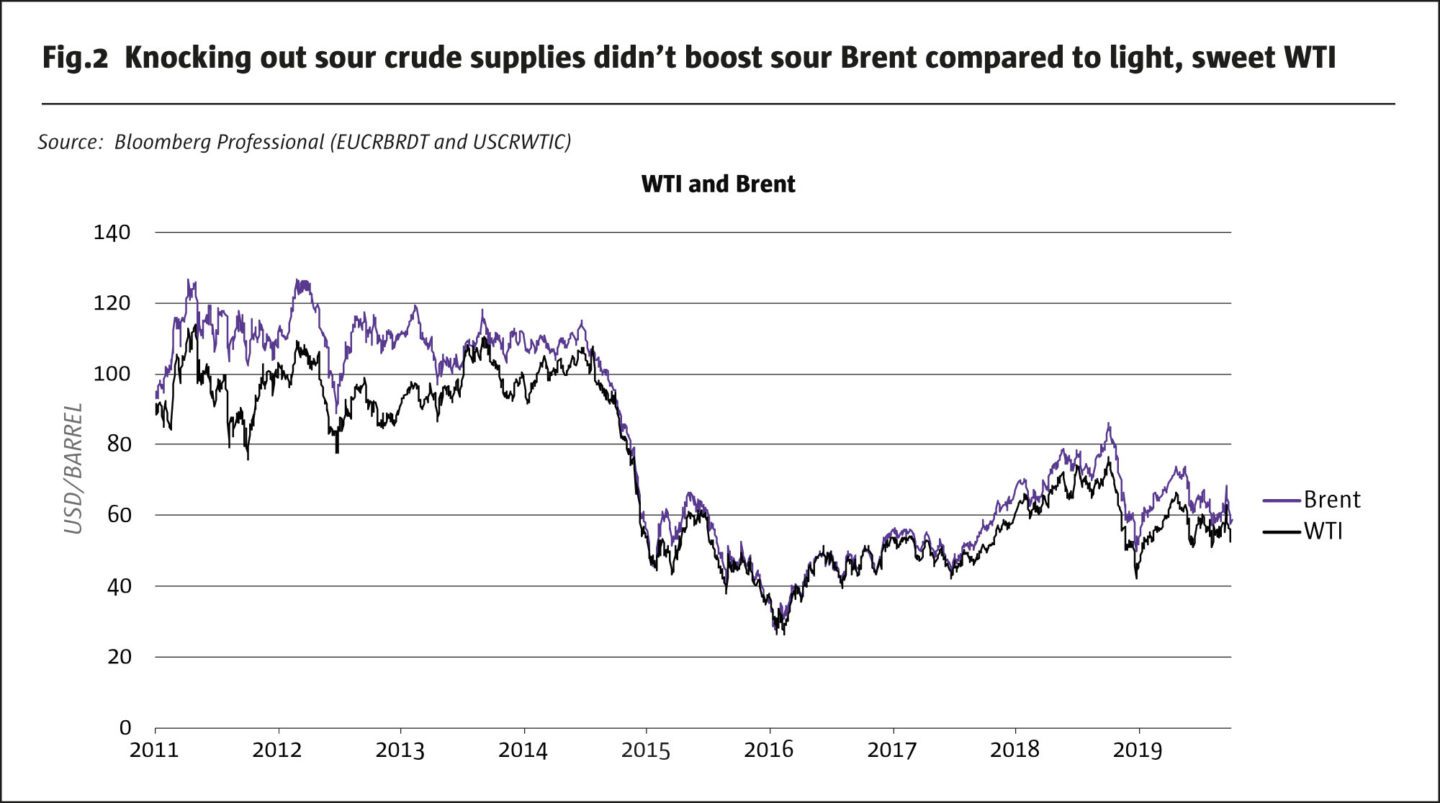

The lack of overall market reaction wasn’t the only surprising feature of the September 14 drone attacks. The Brent-WTI spread didn’t blow out. Given that knocking out half of Saudi Arabia’s sour crude output might have been expected to boost Brent more than a light, sweet crude benchmark like WTI (Fig.2).

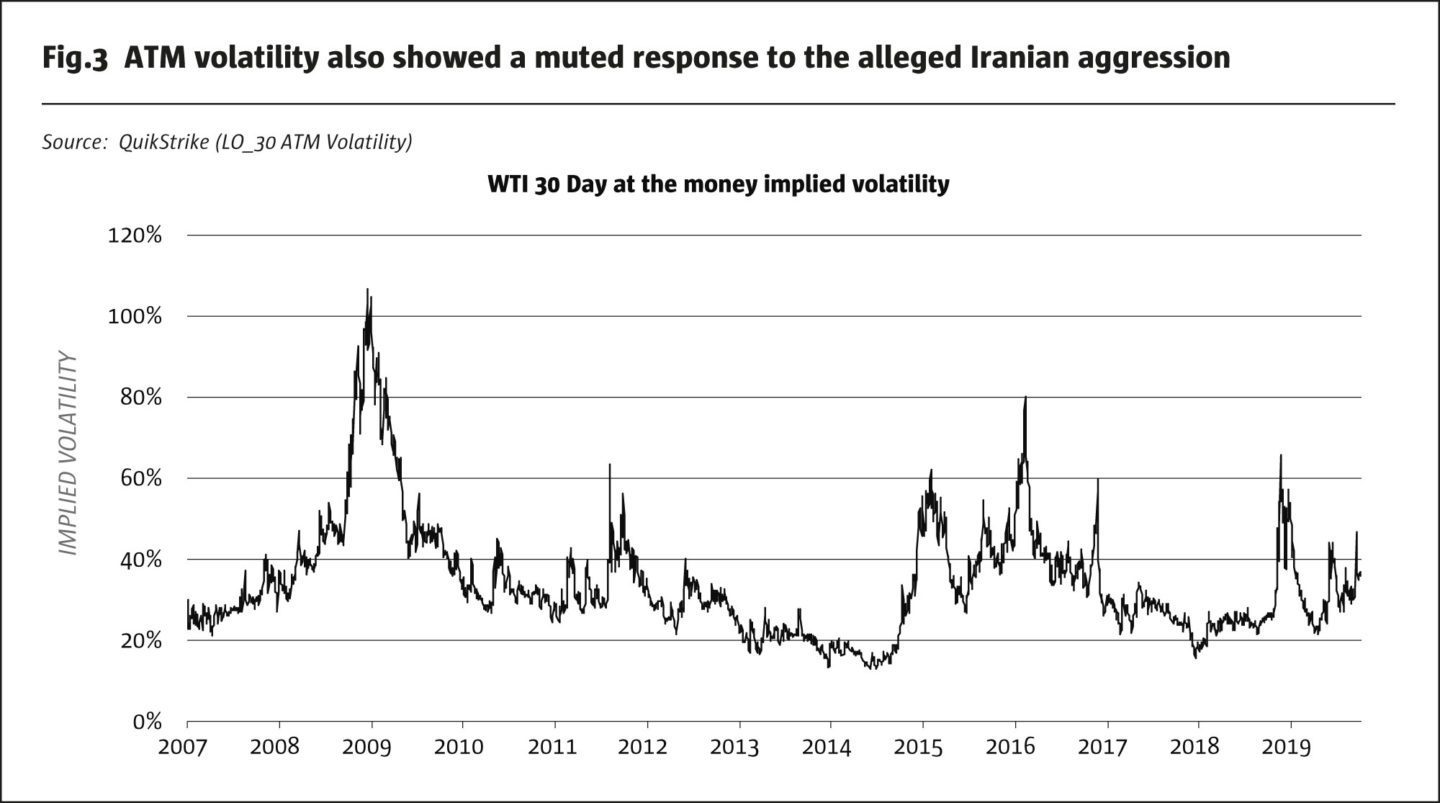

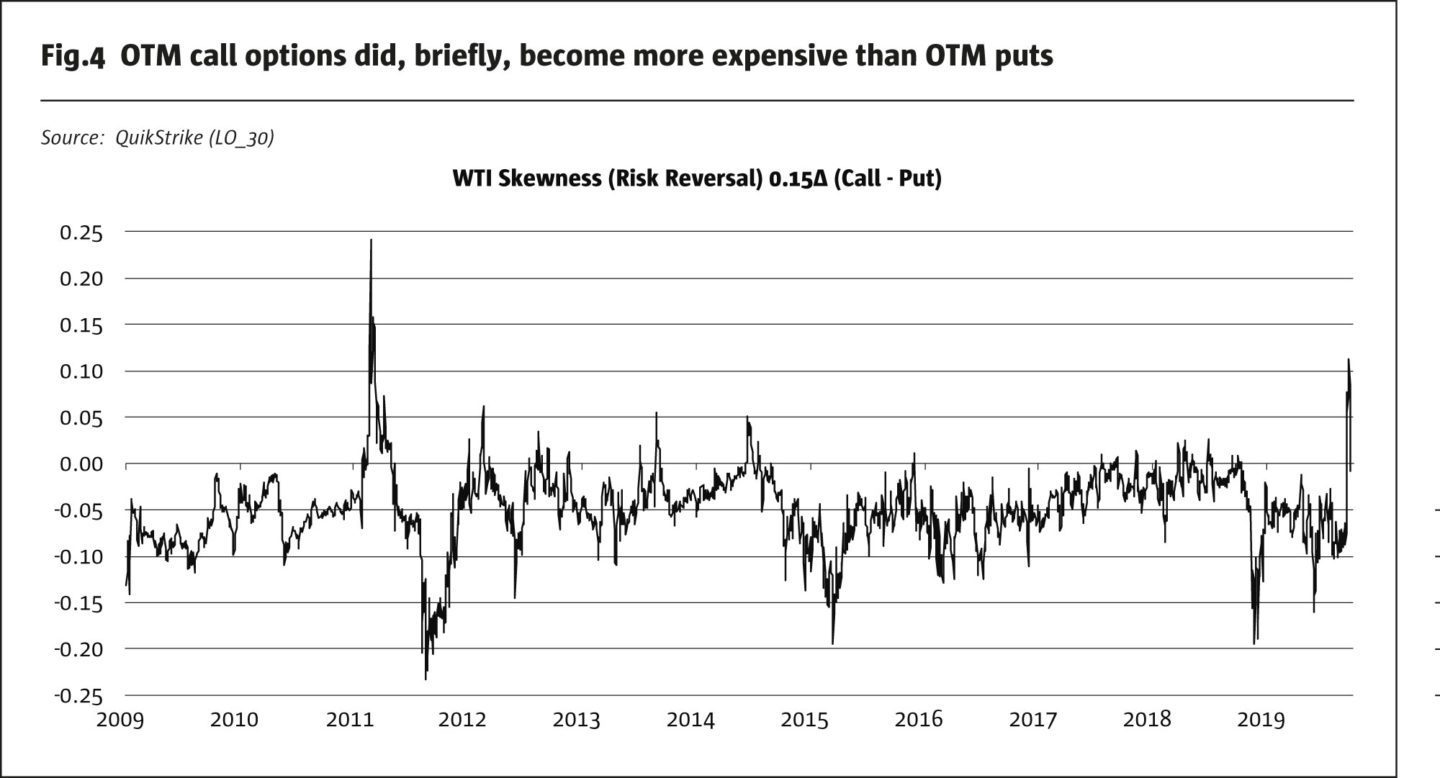

At-the-money (ATM) volatility is now back to where it was before the attacks and, in fact, never rose above the middle of the 2007-2019 range (Fig.3). The only real hint that something was amiss was the skewness of oil options. Normally out-of-the-money (OTM) puts trade at higher implied volatilities than similarly OTM calls. That relationship did reverse, but only for a few days and has now come back to normal (Fig.4).

So why did the oil market’s show such muted reaction? Possibilities abound and include the following:

- The market may have seen the attacks as a one-time deal, a sort of oddity, not to be repeated. Hopefully they’re right, but how can they be sure?

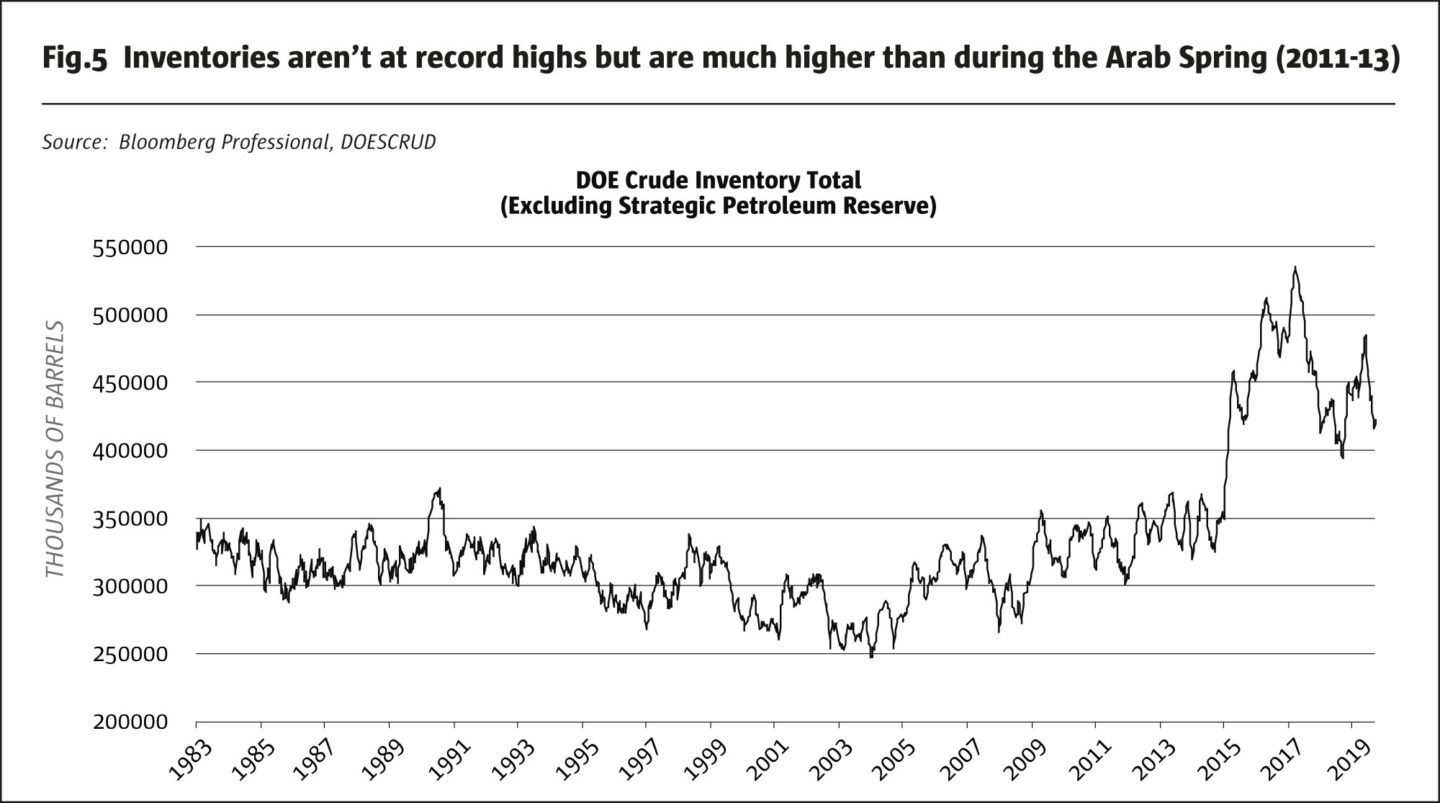

- In contrast with past oil shocks, which occurred during a time of low oil inventories, oil storage remains exceptionally high and may have absorbed a temporary supply shock (Fig.5).

- Global demand is weak. Growth in China, India, Japan, Europe and much of Latin America is slowing. The US may be beginning to slow as well.

- US supplies continue to surge and much, much more US-produced petrol could be brought on line should prices rise to the $70-100 per barrel range. That said, the US produces mostly light sweet crudes which cannot always be refined at the same facilities as sour Saudi crudes.

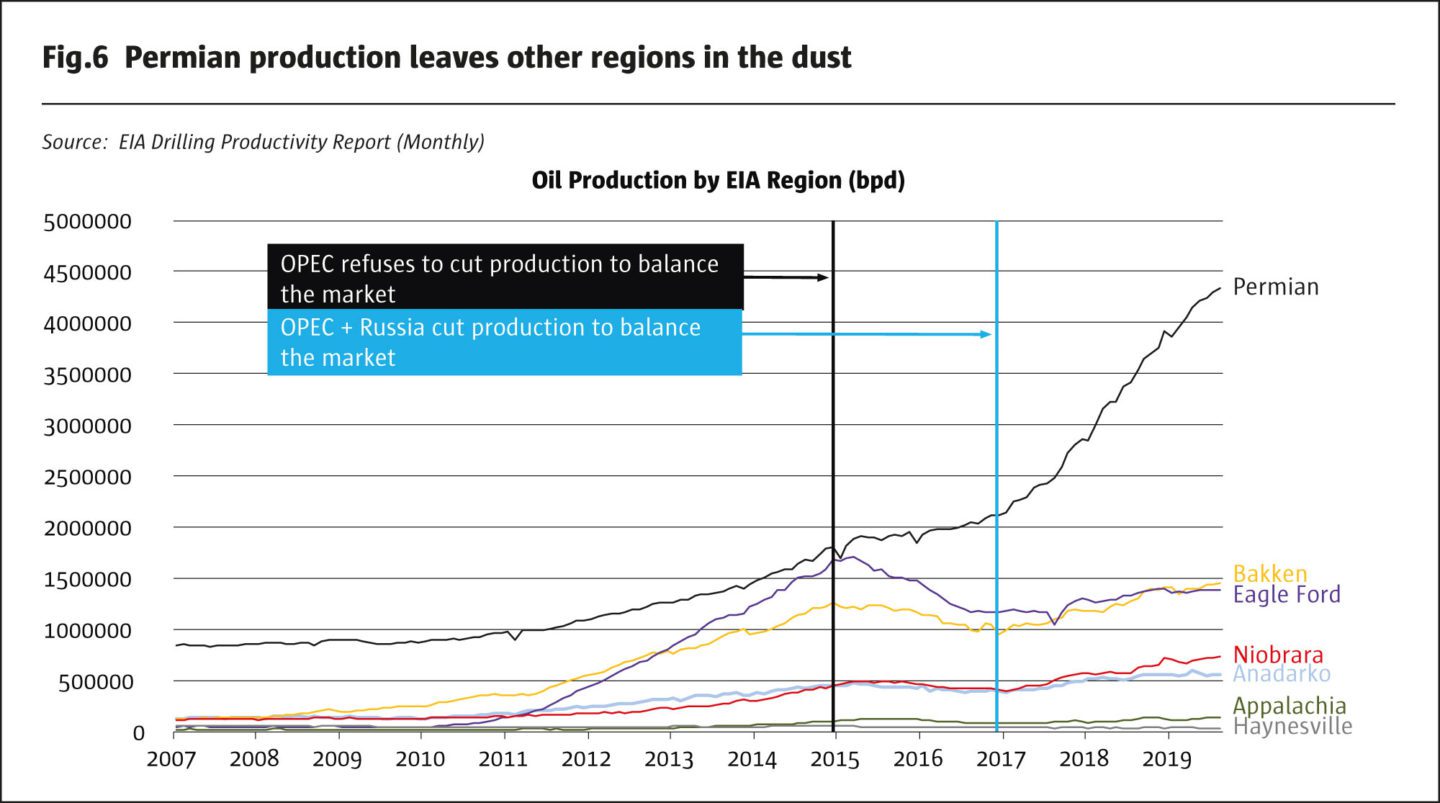

This last point is particularly interesting. While US oil supplies have been rising, most of that increase has come from just one source: the Permian basin. Oil produced in other regions has lagged considerably. Bakken and Eagle Ford production rose quickly until oil prices crashed at the end of 2014. Since then production in those regions never recovered. Nor has there been much increase in production in other regions (Fig.6).

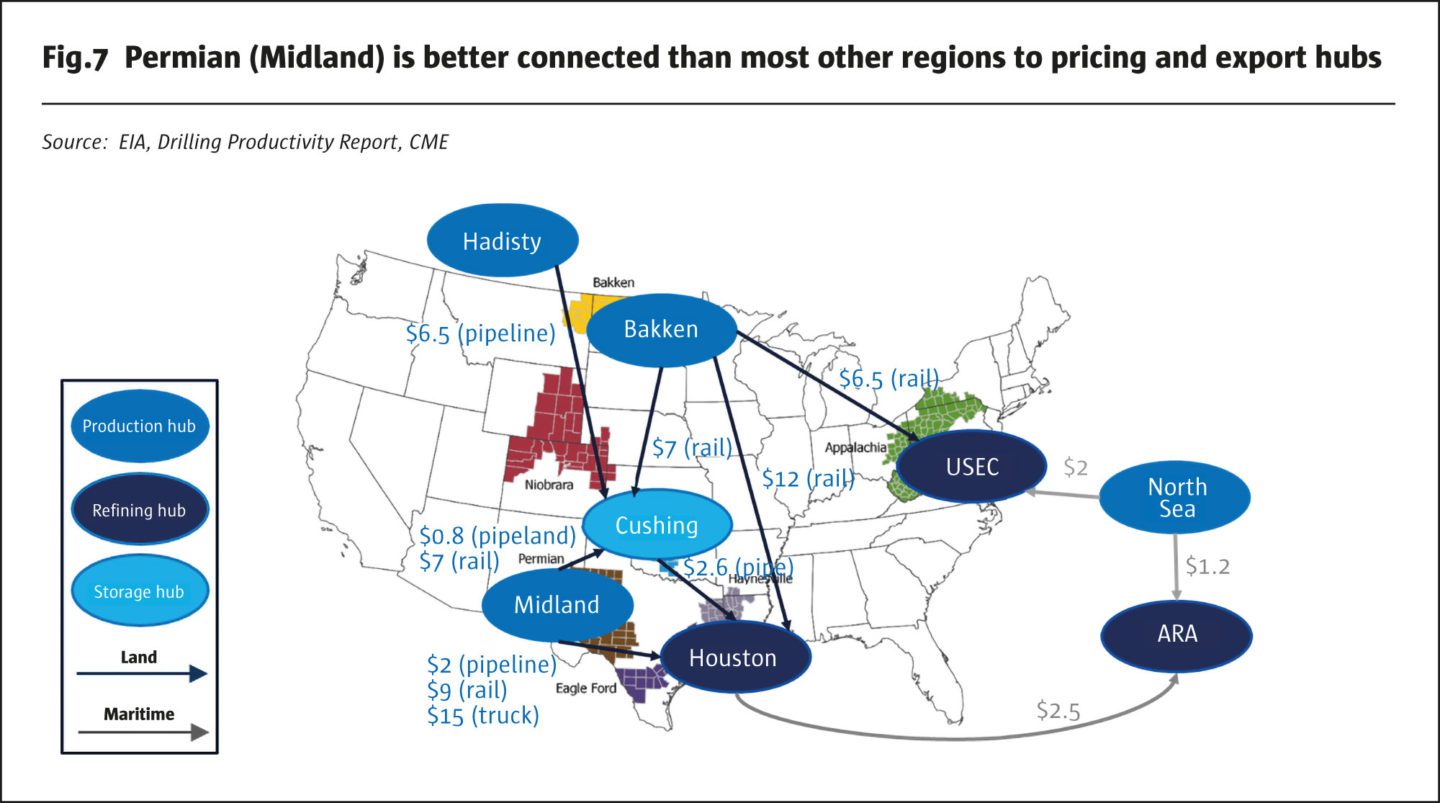

The reason for this is straight forward. The Permian is better connected to the oil hubs in Cushing, Oklahoma and Houston, Texas than the other regions. Transport from Midland, at the heart of the Permian, to Houston costs as little as $2 barrel in a pipeline. By contrast, coming down from the Bakken region in North Dakota, costs around $12 per barrel (Fig.7).

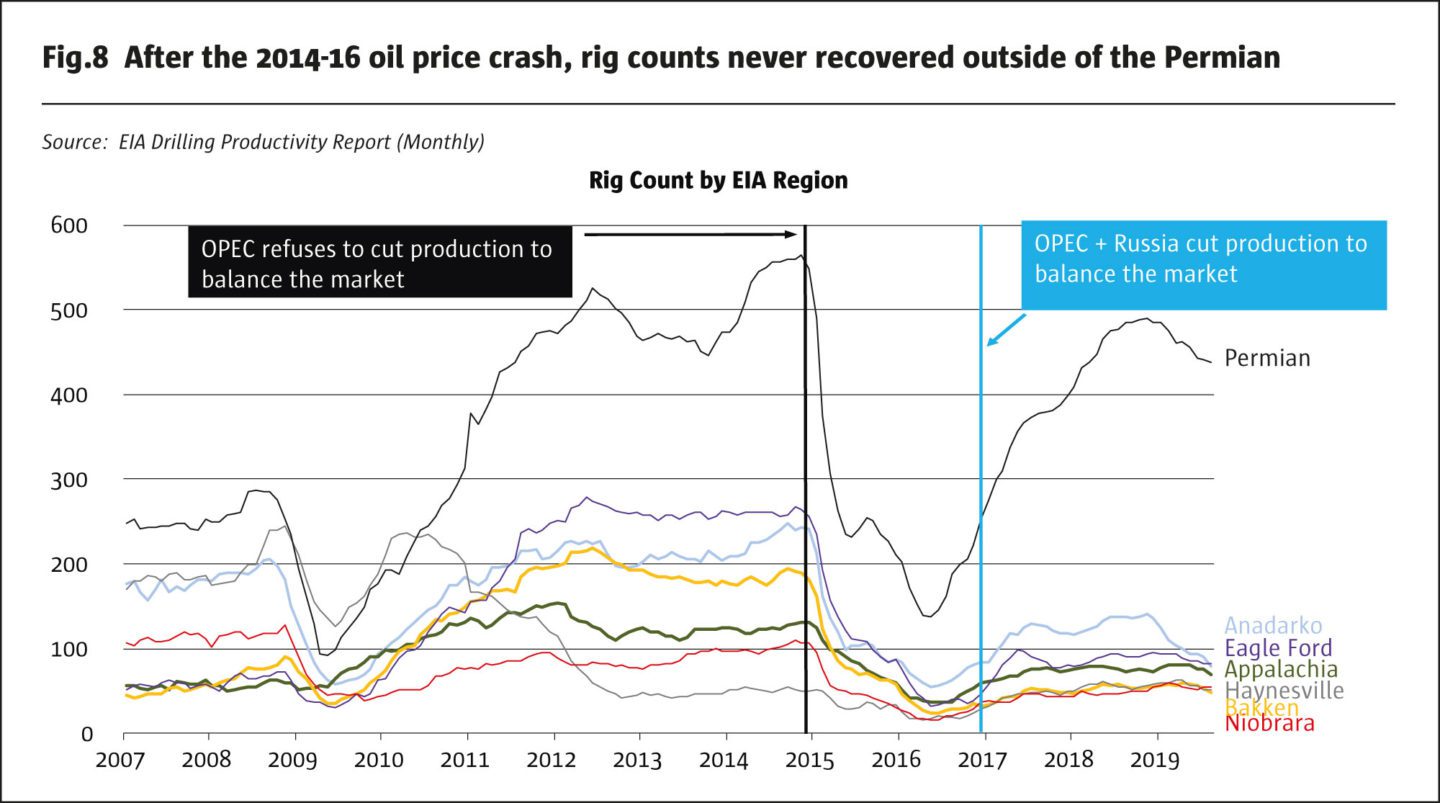

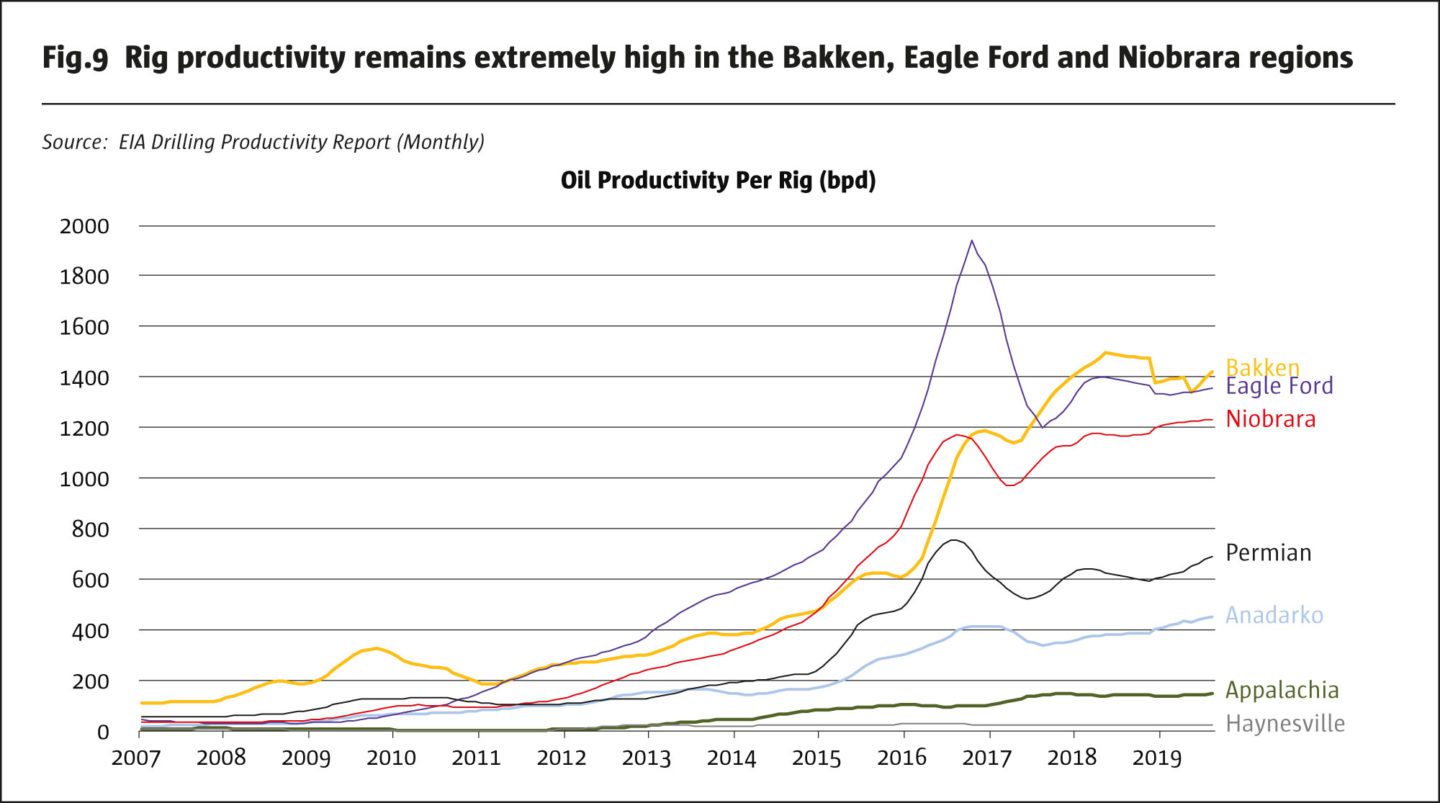

Influenced by transport costs, investment outside of the Permian collapsed after 2014 (Fig.8) even though the productivity of the remaining rigs in those regions remains extremely high (Fig.9).

If oil prices returned sustainably back up to, say, $70 or $80 per barrel, investment could soar in many different US production regions, vastly expanding oil US supplies and, perhaps, offsetting a large portion of any production lost in the Middle East should a lasting conflict develop. Even if US production could rise enough to offset any decline in Middle East production, it could take many months to bring greater production on line. For example, when oil prices hit bottom in February 2016, the number of operating oil rigs did not begin to increase until that June. Production didn’t start rising until October 2016. There could be up to an eight-month lag between a sudden move in prices and a lasting increase in production from the Bakken, Eagle Ford and other producing regions.

As such, we suspect that the muted market response to the events in Saudi Arabia probably had to do with high levels of inventories and soft demand in addition to the possibility of greater US production. That said, the attack on Saudi oil infrastructure crystalized fears about vulnerabilities in the global oil supply that had previous seemed theoretical. During the past few weeks markets have seemed to forget about the attacks and largely ignored warnings from Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that more disruptions could occur in the future. Moreover, outside of Iran, few OPEC countries can do much to expand supply and most of OPEC supply still transits the Persian Gulf where tensions remain very high. This raises the question: are traders taking threats to Persian Gulf oil supplies seriously enough?

Bottom Line

- While oil markets reacted strongly the drone attack on Saudi oil facilities, the price move wasn’t as big as one might have expected given than 6% of global production came off line.

- High inventories might have absorbed some of the impact from lost production

- Soft demand in China, India, Japan and Europe could also have muffled the market reaction

- The possibility of higher US production could also have muted the gains in the oil market.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 144

Is Oil Nervous Enough About Iran and The Saudis?

Pricing geopolitical risk premia

Erik Norland, Senior Economist and Executive Director, CME Group

Originally published in the October 2019 issue