Performance of Alternative Risk Premia (ARP) strategies between January 2016 and October 2018, ranges between approximately +20% and -20%. Many have lost money in the first ten months of 2018, while LFIS’ premia strategy is up 3% in its USD share class. This continues its pattern of outperformance since becoming one of the first premia funds to launch, five years ago. The UCITS version of the strategy has earned The Hedge Fund Journal’s “UCITS Hedge” performance award for best Alternative Beta/Style Premia/Risk Premia Fund.

La Française Investment Solutions (the alternatives and investment solutions business of French asset manager La Française Group, which sits alongside their real estate, long only and direct financing businesses), trades “academic premia”, which comprise the most common premia across the range of asset classes, as well as implied and liquidity carry premia. The latter are: harder to access; often require extensive OTC execution capabilities; capacity constrained; have historically generated higher standalone Sharpe ratios than academic premia. However, the diversification benefit of trading these additional premia is more important for LFIS than the independent return profile of each one.

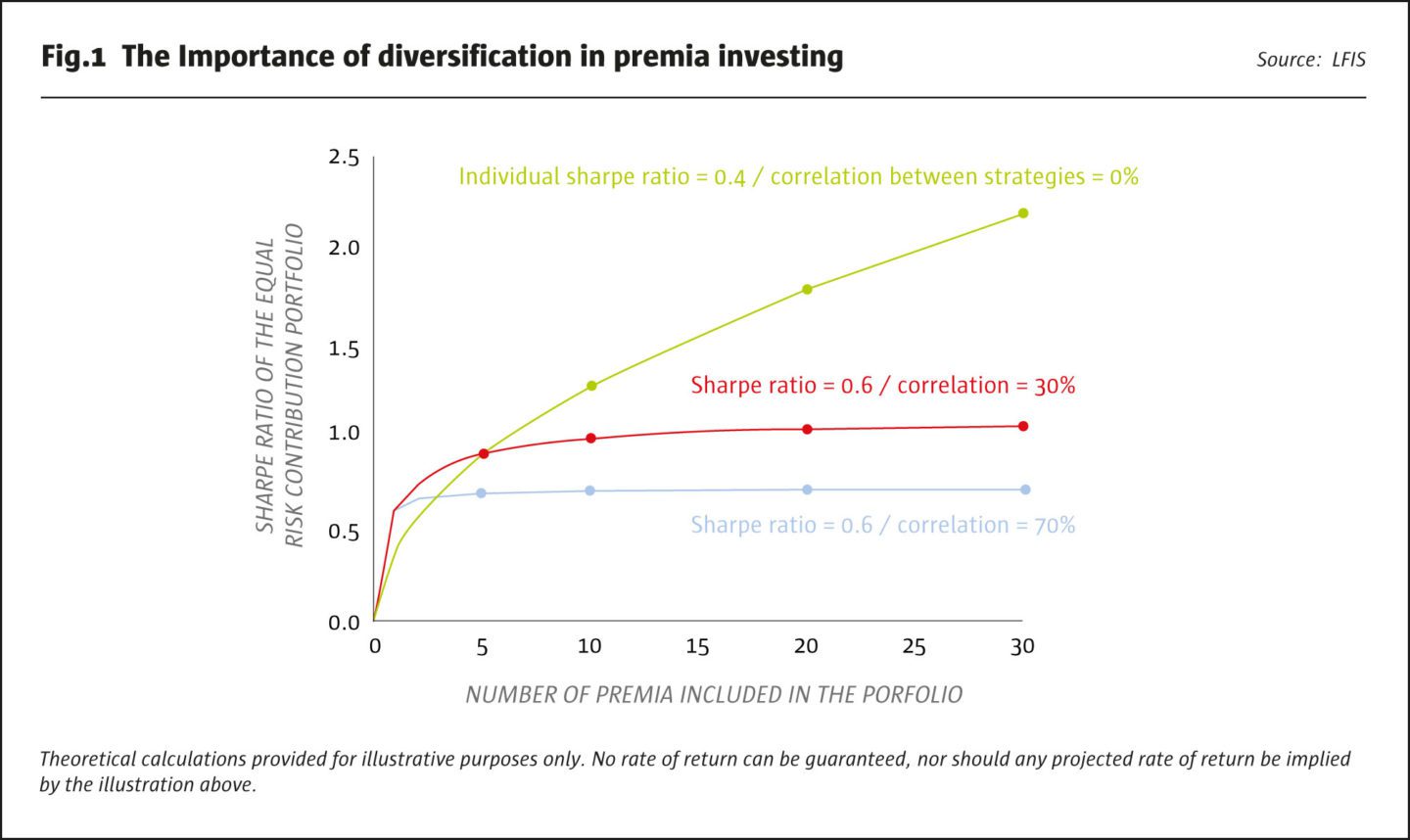

A simplified and stylised simulation exercise (shown in the graph below) demonstrates how strategies with individual Sharpe ratios as low as 0.4, can, if pairwise correlations are zero, generate a portfolio Sharpe as high as two. This is double the Sharpe obtained from a portfolio of strategies with Sharpes of 0.6 but correlations of 30%, which would approximate a traditional multi strategy hedge fund, according to Luc Dumontier, Senior PM and Head of Factor Investing at LFIS. By way of comparison, he observes that most long-only asset classes, such as equities, credit, private equity and real estate, have correlations as high as 70%, which make it difficult to attain a Sharpe of even one over a full cycle.

Even after identifying uncorrelated strategies, it is a volume game: 30 individual strategies are needed to get the Sharpe up to two. An individual strategy is defined as one investment style of premium per asset class, so for example equity momentum is separate from currency momentum, and some premia apply only to certain asset classes, such as dividends on equity.

Back-tests versus live performance

Most ARP strategies show an impressive “back-test” but some have not maintained it during recent live performance. For instance, LFIS’ December 2016 paper Ten Commandments for Alternative Premia Investing cites some academic studies showing how rules-based strategies have realised Sharpes below simulations. In fairness, the jury is still out on whether the back-tests will ultimately prove to be good guides of live performance, as the real-world track record for most ARP strategies is only a few years (at least in commingled fund format), and therefore not a full cycle for most individual premia, let alone for all premia traded.

For this reason, LFIS is very reluctant to show back-tests of its specific strategies. But broadly, Dumontier expects that, “academic premia might produce Sharpes of 0.3 or 0.4, while implied and liquidity/carry premia may generate as much as 0.7 or 0.8, and the basket might aggregate up to 1.5 after diversification benefits”. The live performance of the LFIS strategy, aggregating 30 premia, has generated returns consistent with this: a Sharpe close to two.

Even so, Dumontier reiterates that, “five years does not cover a full cycle for all of the individual alternative premia [1], which could be decades for some of them”. We live in a world of extremes, and equity momentum has produced a Sharpe above one, around triple its long run average, while equity value (applied on a market neutral basis) has actually generated a negative Sharpe.

“We still trust both momentum and value, it is just that value has not been in fashion recently,” he continues. LFIS also has exposure to the momentum or low risk/quality factor in equities, which have performed better than value so far this year. The firm fully expects some premia to lose money for multi-year periods. But given that all of the premia have a positive expected return over the long term, there should be enough cylinders firing to produce positive returns over multi-year periods and ensure the strategy’s diversification profile remains strong.

(L-R): Giselle Comissiong, Head of Marketing and Communications, and Luc Dumontier, Senior PM and Head of Factor Investing, LFIS

Timing factors

This long-term perspective also helps to explain why LFIS are not timing premia. “We try to build the most diversified premia portfolio possible and size them according to an equal risk methodology that considers volatility and correlation,” says Dumontier. Timing premia would throw out of kilter the correlation matrix arithmetic underlying the approach. Removing the diversification benefit of one or more premium, raises the bar for the remaining ones, which would then need to do heavier lifting in terms of their independent Sharpes, in order to hit the target portfolio Sharpe.

Additionally, timing factors would increase transaction costs, which are kept low partly due to average multi-month holding periods.

But confidence in low correlations persisting is the main reason why LFIS does not time factors. This conviction comes not only from low historical correlations, but also, and more importantly, from there being different underlying rationales for various alternative premia.

Rationales for risk premia

Though the simulation talk has “walked the walk”, in millennial argot, its overriding foundation is the a priori rationales for the premia, which need to make intuitive sense.

Academic premia – value, carry, momentum, mean reversion, low risk/quality, and liquidity – have rationales including a reward for bearing an additional risk, whether it is economic or behavioural. These might be bubbles for momentum or corporate distress for value; behavioural biases, such as crowding; and institutional factors, such as some participants being benchmarked and/or unable to borrow.

Dumontier is of the opinion that, “value and size are the only truly pure academic risk premia. Factors such as momentum and low risk contain elements of both risk and style premia. For instance, momentum premia are often explained by the anchoring bias, investors’ tendency to react only gradually to new information. Since momentum factors are also exposed to sudden reversals, rational investors require premia to hold them.”

Implied premia are based on second-order parameters including volatility, correlation, dispersion and dividends. The rationale for associated pricing inefficiencies persisting includes “asymmetries in risk and return and specific flows linked to: certain investor patterns; hedging by banks; insurance companies; commodity producers etc; regulatory constraints,” he says. Liquidity/carry premia including cash versus derivative basis, implied equity index repo rates or convertible arbitrage can arise from other investor constraints (Basel III and Solvency II capital requirements have made it costly for banks and insurers to own certain instruments).

LFIS aims to put on relative value implied premia trades at points in time when carry levels are attractive. Liquidity/carry premia, the third category, profit from a discount because some investors who lack the cash, regulatory remit or tolerance of volatility cannot hold certain assets. This artificially segments markets. It is important to note that liquidity premia are not about picking up illiquidity premia, but rather about providing liquidity, in the form of cash, to implement certain types of trades.

Investment universe and instruments

Liquidity/carry premia mainly relate to equity and bond markets while academic premia can be invested in across all asset classes (equities, bonds, currencies and commodities). Implied premia can be traded in relation to equities, bonds, currencies, credit and commodities. Notably, “commodity markets have historically been a particularly rich source of volatility premia,” says Dumontier.

Academic premia are implemented via plain vanilla, linear, delta-one instruments, such as futures, forwards and swaps. Implied premia are implemented through derivative instruments, such as variance swaps, options, and other swaps, that can have a non-linear payoff profile with respect to some performance drivers. Liquidity/carry premia use a mix of cash and derivative instruments.

LFIS applies premia across more asset classes, geographies and instruments than do some managers, which produces some diversification benefit, even for the traditional academic premia, but this is more about controlling security-specific risk. For instance, single stock, currency and government bond position sizes are also controlled. “What matters more for diversification is the orthogonal strategies in implied premia, and liquidity/carry premia,” says Dumontier.

Whereas most financial markets see a big spike in correlations during panics, our premia see only a slight uptick on down market days.

Luc Dumontier, Senior PM and Head of Factor Investing, LFIS

Maintaining low correlations

Indeed, correlations between the three families of premia have been near zero. Importantly these are stable through changing market regimes. “Whereas most financial markets see a big spike in correlations during panics, our premia see only a slight uptick on down market days,” says Dumontier.

This is crucial, because the key premise of the strategy falls away if correlations shoot up during a market selloff. Dumontier dubs the tendency of correlations to increase as “re-correlation” and discusses it in an October 2016 research paper entitled, Why Re-Correlation Matters in Alternative Premia Investing. For example, 2015 saw currency carry trade premia and equity value premia re-correlate. And in January 2015, “an investor that had overlaid carry, value and momentum premia in the currency universe would likely have accumulated three short positions in the Swiss franc,” he points out.

Defining factors

The core objective of maintaining low correlations determines how LFIS defines its factors. Individual factors can have some correlation with generic factors but should have very low pairwise correlation with one another.

This means that if two sub-strategies – such as liquidity and curve premia in commodity trading – are both “time spread” strategies, and are highly correlated, the pair will be combined into one premia. Similarly, in equities the low-risk and quality factors are combined, as Dumontier explains, “low risk is a symptom of the cause, which is high fundamental quality”.

The firm does not in fact want a high negative correlation any more than they want a high positive one. The strategy is seeking correlations near to zero. For instance, the low risk factor is usually expensive stocks, which would result in a negative correlation with the value factor, so valuation outliers within the low risk universe are removed, in order to reduce the negative correlation with the value factor. Equity factors are also controlled for market capitalisation groups to avoid an unintended negative size bet.

The firm’s factors show some correlation to generic factors, but Dumontier believes theirs are more robust – in that the back-tests of the factors are less sensitive to changes in parameters. If a factor only works with very precisely and narrowly-defined parameters, it may be “overfitted” and might be more prone to decay. For instance, LFIS’s equity low-risk factor continued to generate a decent Sharpe ratio even with variations in the number of stocks, rebalancing frequency and calculation window.

Avoiding directionality

Just as important as low correlation among the premia is low correlation to conventional asset classes. LFIS has consciously designed its strategies to avoid explicit or implicit directionality. Absolute performance of the LFIS strategy has been close to flat on tumultuous days such as the day of the Brexit vote, Trump’s election, or Wednesday 17th October 2018, when US equities dropped by 3.5% in a day. Differently, some ARP strategies have lost money in February and October 2018, though we should repeat the caveat that this may not be sufficient data to have statistical confidence in their equity correlation. There may however be a priori reasons for thinking that some ARP strategies could have inherent or structural directional exposures.

If any ARP strategies applied risk premia to long-only portfolios, that would be a different strategy – “smart beta”.

But trend-following CTAs strategies in some ARP programmes do explicitly take both long and short directional positions, which has recently resulted in long equity exposure causing losses. LFIS avoids this by implementing the momentum factor for equities on a market neutral basis, and with some extra filters. “The equity market is split into high beta, medium beta and low beta tranches, and long/short momentum portfolios are constructed within each tranche,” says Dumontier.

Similarly, with another academic risk premium that has historically shown positive correlation with risk appetite – currency carry – LFIS seeks to pick up some carry from pairs of currencies that have a similar risk beta. So, it may own the Australian Dollar against the New Zealand Dollar, but would not be likely to trade either against “safe haven” currencies such as the Swiss Franc or Japanese Yen.

However, LFIS research papers explain how adjusting for historical betas can throw up other complications. Implementing the low risk equity factor on a beta neutral basis can still end up being, in effect, short of value and short of small caps. It also implies a net long position, in cash or nominal terms, because low risk stocks have historically shown much lower beta. But during a severe market sell-off, betas compress and low risk stocks can fall just as fast as others, resulting in an unexpected positive equity market correlation. The reverse dynamics apply when betas decompress, or when beta dispersion increases. Then, a supposedly market neutral momentum strategy can become long low beta, and short high beta stocks, creating negative beta-adjusted exposure. Thus, betas of premia strategies are moving targets and models need to keep pace.

90%

The weekly dealing Luxembourg SICAV has a 90% strategy overlap with the daily vehicle, but slightly more freedom to pursue some trades, particularly in commodity markets.

Implied and liquidity/carry premia

Notwithstanding their great diversification benefit, implied and liquidity/carry premia strategies can also result in implicitly directional exposure, depending on trade construction. For instance, rather like long currency carry, trading implied versus realised volatility in certain equity or commodity markets, can produce long risk exposure, simply because realised equity and commodity volatility have some correlation with general risk appetite. This potential directionality could be mitigated by trading the spreads on a relative value basis, for instance between two commodities, such as gold and silver, as discussed in LFIS’ December 2015 paper Commodity premia: It’s all about risk control, (which identifies factors under all three of its premia umbrellas: intra-curve premia (curve, liquidity), inter-commodity premia (trend, carry/value) and volatility premia).

Accidental beta bets can also arise where the front month of a commodity contract has higher beta than more distant months. Then sizing the two equally in a calendar spread/horizontal spread/curve trade can result in unintended long or short beta. The ratio needs to be calibrated to the betas in order to try and construct a beta-neutral spread. (In practice, this is not straightforward as choices over lookback periods feed into and change beta forecasts).

Apparently relative value curve strategies executed between different commodities can also introduce directional wagers on particular sectors, which can be a significant source of volatility particularly because correlations between commodity sectors are low; for instance, crude oil and natural gas have in November 2018 made violent moves in opposite directions. Time spread strategies should also take account of the fact that some calendar spreads are more volatile than others.

Betas apart, commodity trading needs to heed non-financial data. LFIS historical analysis suggests a commodity curve strategy that owned the three-month versus the front month contract, could lose money due to seasonal or weather factors. This could be mitigated by considering spreads of contracts that belong to the same season.

“Premia 2.0”

LFIS view their approach as “Premia 2.0”. LFIS has a broader perspective on premia: it uses technical, fundamental and behavioural data inputs; it trades a larger number of premia sub-strategies; and it applies them to a wider range of markets, including both exchange traded markets and over the counter (OTC) ones.

LFIS has more variety across each of these axes than the majority of ARP strategies we have seen. At one end of the spectrum, the most “plain vanilla” ARP strategies (including some wrapped in ETFs) may only trade three or four generic risk premia, over perhaps 30 or 40 exchange traded markets, using linear instruments, whereas LFIS is trading about 30 premia, over hundreds of markets, including implied and derivative markets, and including non-linear instruments.

Discretionary execution for implied and liquidity/carry premia

LFIS is also differentiated by using some discretion in clearly defined areas. Virtually all systematic managers exercise some discretion in driving forward their research process, but LFIS has somewhat more discretion than some systematic managers, over the investment universe, and over executing signals.

Discretion over the investment universe is not that unusual and LFIS has applied this twice, removing markets from the academic premia family. For instance, in January 2014, before the Swiss National Bank de-pegged the Swiss Franc, LFIS ceased trading the currency because it was “too dangerous” says Dumontier (since the Swissie floated it has been reintroduced). And in 2016, the Japanese 10-year bond was removed, after the Bank of Japan set a target yield range (of 0-10 basis points) so tight that there would not be enough volatility or carry to implement trades such as momentum and carry.

What’s more unusual for a systematic strategy is that LFIS has to use discretion to determine whether sufficient market liquidity exists to obtain good execution for certain signals. Some systematic managers have completely automated execution by trading only electronic markets and use algorithms to do so. LFIS trades OTC markets which are not electronic, and where human traders interact.

For the implied and carry/liquidity families of premia, systematic screens flag up potential entry points, but acting on these signals is subject to an execution feasibility constraint because they are OTC markets. “For instance, one of the credit market signals might identify negative basis between cash and derivatives, but to implement the signal, we need to source cash bonds from one or more counterparties and related derivatives from different counterparties and need to obtain competitive prices. If there is insufficient liquidity to execute the trade in the intended size, and/or an indication of interest leads counterparties to offer inferior pricing, it may not be worth putting the trade on,” explains Dumontier.

LFIS often needs to use different counterparties for specific markets and works with 25 of them, sometimes including niche players rather than bulge bracket global investment banks. For instance, “the four or five counterparties that give good prices on gold or silver volatility, are not the same ones that give keen quotes on currency volatility,” says Dumontier.

Evolution and future research

Some managers emphasise the proprietary nature of their factors, and recently many are making use of alternative data. Dumontier’s analysis suggests that some factors with new names can turn out to be correlated with existing ones, and therefore akin to a new bottle for old wine. Having spent many years researching risk and style premia, Dumontier admits, “it is getting harder to find new ones that add value in terms of being orthogonal to the existing basket”.

LFIS does not claim to have discovered novel factors in the first place; the firm is essentially curating tried and tested factors, fine-tuning their design, combining them in an uncorrelated way, and implementing and executing them carefully.

Nonetheless, the company is exploring new areas of research, partly through external partnerships. The firm’s Head of Marketing and Communications, Giselle Comissiong, who featured in The Hedge Fund Journal’s ‘50 Leading Women in Hedge Funds 2018’ report in association with EY, has spearheaded a three-year quantitative research partnership – Quantitative Management Initiative (QMI) – a Paris-based research initiative that brings together leading scientists and researchers to study quantitative approaches in asset management. It includes teams from University of Paris Dauphine, and ENSAE. Research projects include artificial intelligence, big data, machine learning and alternative data, risk and crowding, algo and medium frequency trading. LFIS has a partnership with SESAMm, which also researches how to apply big data, artificial intelligence, and alternative data to financial markets. In another collaboration with academia and the asset management industry, Comissiong launched the inaugural Quant Vision Summit held in Paris in 2018.

A new sub-strategy, which will seek to profit from short-term over-reaction to economic or corporate news, and the subsequent mean reversion, has just started being implemented. This strategy could have holding periods as short as hours or days. LFIS will initially allocate a very small risk budget to get comfortable with the setup and may steadily increase the allocation over time.

It is also worth noting that LFIS premia strategies do not cover all risk premia, partly as some do not fit into weekly or daily dealing funds, but could be harvested by other LFIS strategies, that can have monthly or quarterly liquidity. Two examples could be certain trades involving insurance-linked or inflation-linked securities, which Dumontier judges are not liquid enough for its premia strategies for the time being.

Persistence and crowding

In general, LFIS does not revise individual factors too often, as Dumontier fears this could leave them prey to overfitting. The overriding requirement is that the team continue to see an intuitive reason for the risk premium. Hypothetically, LFIS might remove a signal if the rationale disappeared – but not if it was simply showing a low or negative Sharpe ratio. For instance, structured products may depress the valuation of implied volatility; if such products disappeared, the firm might revisit that premia.

LFIS are confident that returns from premia will persist. Risk premia are undiversifiable rewards for taking on systematic risks such as corporate distress in value stocks, or lack of geographic diversification in some small cap stocks, and should not be eroded by more investor interest, as investors need the reward for taking the risk.

Implied and liquidity/carry premia face barriers to entry in terms of investment infrastructure, cash or regulation, that can profit from behavioural factors, investment constraints and structural flows. LFIS are of the opinion that these constraints allow these premia to persist – but that more capital chasing these strategies could decay returns. Hence LFIS does have disciplined capacity limits.

Vehicles

LFIS has three premia vehicles. The flagship is a daily dealing UCITS containing around EUR 2 billion. A weekly dealing Luxembourg SICAV, with EUR 800 million of assets, has a 90% strategy overlap with the daily vehicle, but slightly more freedom to pursue some trades, particularly in commodity markets, that are not permissable under UCITS regulation. Taken together, these two are close to their target capacity of EUR 3 billion. A more scalable premia UCITS strategy, focusing mainly on the academic and implied premia, has been launched.

Assets have come from institutional investors, including asset managers, wealth managers, insurance companies, pensions, SWFs, endowments, based in the EMEA, North America and Asia (including Australia). Asset raising has gone well, overall up from $2 to $14 billion since 2015 for LFIS as a whole.

With all this high touch trading – and nuanced judgements around the design and implementation of factors – machines are not going to replace humans any time soon at LFIS. THFJ

[1] Alternatively, ‘risk premia’, ‘style premia’, ‘style factors’, ‘risk factors’, ‘ factor premiums’, etc.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical