The Hedge Fund Journal ‘Europe 50’ manager, pan-European Candriam Investors Group (a New York Life Company) may be renowned for its liquid alternatives, single-strategy products, but it also has a strong, and quite separate, multi-manager franchise. Candriam’s flagship fund of hedge funds strategy, Candriam World Alternative Alphamax (CWA), has delivered an unusually stable and lowly correlated return profile, with only one losing year since inception in 2001, when Co-Head of External Multi-Management, Maia Ferrand, joined the firm. Amid downsizing and many mergers in the fund of funds industry post-crisis, Candriam’s multi-manager team has remained constant and independent, demonstrating the loyalty and long-term commitment of Candriam’s long-standing management, which does not use the multi-manager assets to seed or support its single-manager products. Candriam’s multi-manager division has retained its continuous track record, stable team, consistent process and independent mind-set throughout the credit crisis, former owner Dexia’s difficulties, and the concomitant outflows. Now the new Candriam owner, New York Life Investments (NYLIM, a wholly owned subsidiary of New York Life), has provided a renewed momentum to the business. We met with Maia Ferrand, who was also selected as one of The Hedge Fund Journal’s “50 Leading Women in Hedge Funds 2015” in the survey sponsored by EY, to find out what differentiates Candriam’s distinctive approach to manager selection and portfolio construction.

The Candriam culture

Ferrand left Lebanon due it its civil war, but her mother country has an enduring influence. “It is a multi-faith and multi-cultural country with a long history of survival and renaissance,” she says. “My own career and the Candriam story relate to that.” Thus Ferrand’s mentors and colleagues over the years have been drawn “from very different horizons, including Italians, Iranians, French and Americans, from Paris, the UK and Hong Kong” – and she has helped to build a multi-cultural team at Candriam: French nationals work alongside “one Portuguese, two Belgians, and a Chinese”. Ferrand started her career at CCF (now HSBC) and then moved to Credit Agricole, which sent her to the US. The next episode was at Lehman Brothers in London, before Ferrand’s one-time boss from Credit Agricole then hired her again at Credit Lyonnais – and gave her a big break, asking her to set up an FX options desk in New York.

Option trading uses another key part of Candriam’s process: quantitative analysis. Ferrand studied Econometrics at university and this informed analysis of options in terms of “being able to look at tail risk, volatility risk, volatility surfaces, and other risk metrics.” But psychological qualities were also important during her 14 years trading foreign exchange options: “The currency market is one of the world’s largest, with no long-term arbitrage, so you have to buy and sell very fast, react with your gut and monitor your P&L every day, taking risk and not having an ego about what is being bought or sold,” she recalls.

This fast-paced world gave her an affinity with Candriam’s Chief Investment Officer, Naïm Abou-Jaoudé, who also has a trading background – and lured Ferrand to the buy side. “He saw the added value that I could bring to the table and offered me a job with what was at the time Dexia in 2001,” she says. Just three years later, in 2004, Ferrand was asked to run the multi-manager investment team with Jean-Gabriel Nicolay, and the pair have co-managed it ever since. The partnership is complementary, as Nicolay comes from a capital markets background on the fixed income side and is “more quantitative and analytical”, Ferrand has found. They have worked well together for so long because “We have the same responsibilities but different approaches, leading to a solid combination,” she is pleased to say.

Consensus decision-making

Ferrand and Nicolay “tend to agree most of the time but not all of the time.” But they do not agree to differ, given the collegiate approach. Ferrand likes to “federate the team so that each team member is instrumental to the group.” All eight key team members on the alternatives side tend to see all of the funds and give feedback. Each fund has one lead analyst who will present it to the team. Ferrand and Nicolay run the business and have the final say but could be vetoed by Candriam’s risk management team, although this has only happened once. Prerequisites for risk management, including independent valuation, independent third parties, segregated custody of assets, and sound counterparty risk management policies have become industry standard post-2008, but pre-crisis plenty of funds that subsequently failed, or proved to be frauds, would have failed these tests.

The risk management team always has plenty of other questions on managers, and they write their own operational due diligence questionnaires on funds, with inputs including background checks, document reviews by a legal team, and site visits. The process takes a few months, although Ferrand thinks it might take a few weeks if that was all they were doing, which implies a triple-digit number of hours for multiple people. Indeed, Candriam tends to meet managers three or four times before investing, as well as “making a point of talking to analysts to see how people think about their leaders.” Operational and risk teams make separate visits.

The longevity of most team members matches the tenure of Ferrand and Nicolay, who built it together. The team’s shared working lives have generated institutional memory: the group has created a “huge database of intellectual property that stays in house, with tons of contacts, including former US ones, and access to information.” These qualitative inputs carry more weight than Ferrand and Nicolay’s quantitative backgrounds in manager selection, because “quant tools are past history and those that did well before may not do well in future.” Adds Ferrand, “it’s a people business, and we view managers as long-term partners in our fund, as our average holding period is long with some managers still in the book since 2004 and portfolio turnover averaging 15% per year.”

Maintaining uncorrelated portfolios under QE

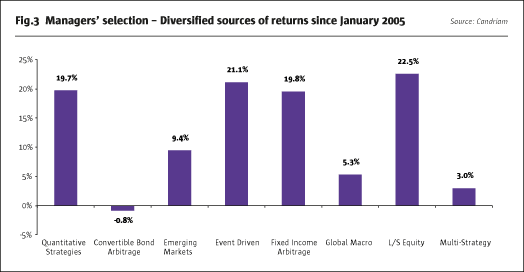

But Ferrand thinks that skill at selecting managers is not enough to create a strong fund of funds product, and quant analysis plays a greater role in portfolio construction, particularly to identify factor exposures, correlations, and compare managers based on Sharpes, Sortinos, draw-downs and so on. Candriam’s long average holding periods for funds have been sustainable partly because the portfolio has maintained strong diversification. Candriam looks for decorrelation not only between strategies, but also between managers within strategies, and aims to avoid binary themes or over-crowded and fashionable strategies dominating the portfolio. Even in a post-2008 world, when QE has been blamed for increasing correlations between securities, markets and asset classes, “correlations between buckets are very low, and sometimes negative, by construction,” asserts Ferrand. To this end, “We dig deeper into managersto avoid unintended factor exposures or hidden correlation risks,” Ferrand explains. For example, when QE started in 2009, Candriam noticed that global macro funds only seemed to be profiting from long equity exposure. Since this triplicated the equity exposure in their long-biased long/short equity funds and event-driven funds, Candriam redeemed from macro funds. Emerging markets were avoided for similar reasons, and Candriam’s alternative multi-manager products only started returning to emerging markets in late 2015.

Return attribution

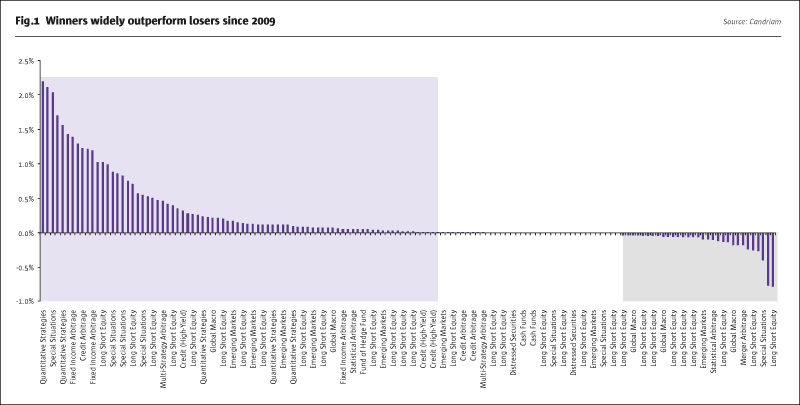

Over time, each of the four broad buckets (event driven, long/short, fixed income and quantitative strategies) have all made positive, and roughly equal, contributions. But contributions from individual managers have varied hugely, with the fat tail sitting on the left hand side. Although many alternative strategies that are collecting risk premiums will naturally show a negative skew, the distribution of returns from Candriam’s allocations shows a huge positive skew: winning funds beat losing funds by a factor of seven since 2009, as shown in Fig.1.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

The worst performer was a short-biased manager who has since returned capital to managers. Ferrand does not entirely regret this allocation because the CWA fund of funds preserved capital in 2011, partly due to two short-biased managers.

‘Emerging’ managers

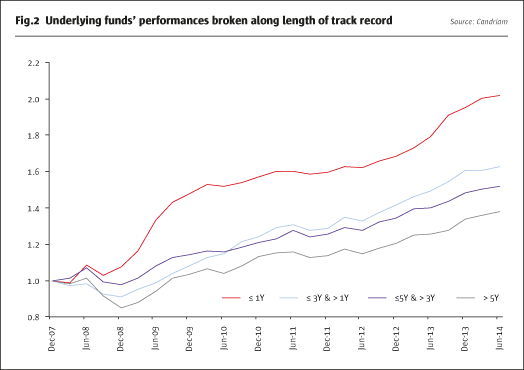

Smaller managers have made a disproportionate contribution to returns, as shown in Fig.2.

Though some in the industry insist that start-ups need many hundreds of millions, Ferrand continues to champion selected smaller, and earlier stage, managers, often known as ‘emerging’ managers (not to be confused with emerging markets managers) and takes pride in having been one of the first investors in some funds that became industry leaders. While many managers of CWA investee funds are based in the main financial centres of London and New York, Ferrand and Nicolay have also found talent in smaller funds located off the beaten track, in smaller financial centres such as Sweden and Norway.

Of course, Candriam’s potential to invest in smaller funds is subject to practical constraints and normal due diligence. An indirect limit arises from Candriam’s desire not to go above 15% of fund (not firm) level assets; given typical tickets around $10 million at current asset levels around $450 million, that implies a $60 million minimum for fund assets. Business continuity is also important. “We need managers to be at break-even, otherwise we are paying for them to set up their operations,” says Ferrand, and she is sometimes pleased to see entrepreneurial founders forego their own salaries for a few years. Indeed, Candriam wants to have confidence that a team can continue for at least three years without growing assets. Candriam has at times invested in founder share classes with discounted fees, but is not currently allocating enough to negotiate discounts on a bilateral basis. These criteria together will tend to imply that Candriam seriously contemplates allocating to funds with assets of at least $50 million to $100 million for discretionary strategies.

Quantitative strategies

Quantitative strategies are subject to a higher assets bar, however. Candriam does not invest in the smallest quantitative managers because Ferrand thinks“barriers to entry are high as managers need to invest in systems, research, IT, and execution. If they do not invest and their assets grow it is dangerous.” Furthermore, she warns, “Historical hypothetical performance or ‘backtests’ must be treated with caution,” and “paper-trading records have to be discounted to reflect market frictions, slippage, execution, and so on – we prefer real money track records”. Candriam needs hard daily data to validate the returns and see how they dovetail with those of other funds, in part because quant funds will not reveal their ‘secret sauce’. Factor over-crowding is intolerable, so “We make sure they are not all in the same factors to try and avoid synchronised reversals, and we need lots of data to determine this,” she explains. All of this implies a higher minimum firm-level asset size for investible quant strategies, but Ferrand is also wary of quantitative managers growing too large, as “inefficiencies can disappear very quickly with too much assets and kill a business” – so she respects those quant managers who have been disciplined about closing strategies.

Quantitative strategies have made a strong contribution to Candriam returns, pre- and post-crisis. Though the post-crisis climate for many traditional trend-following CTAs has generally been lacklustre (bar 2014), Candriam’s quant bucket exploits the diversity of the CTA, and broader systematic, hedge fund universes. Strategies have included mean reversion, statistical arbitrage, pattern recognition, and some shorter-term approaches.

Alpha key for equity managers

Candriam’s quant allocations have outperformed managed futures hedge fund strategy indices. But in long/short equity, where Candriam launched a multi-manager CWA Global Long Short Equity strategy in 2006, Candriam will not necessarily avoid managers that have lagged the long/short equity index during a bull market – because clearly a significant proportion of its returns have come from equity beta.

Instead, Ferrand prefers to limit net equity exposure to no more than 20-30%, and has recently increased the proportion of market-neutral managers. She has selected more sector specialist managers focused on industries with high dispersion of returns – and, therefore, potential for alpha generation. Technology is an example where the clash between innovation, creating big winners, and obsolescence, leading to big losers, is ideal for stock-pickers. Ferrand thinks they need to stay small and nimble in terms of assets, and has several broadly market-neutral technology specialists that are extracting alpha from sectors such as hardware, semiconductors, and social media. Three of the managers are situated in California, near Silicon Valley, the epicentre of the global technology industry.

Healthcare is another industry where ex-doctors may obtain an edge by “really understanding new medicines, regulations, legal problems and political changes,” explains Ferrand, and one of Candriam’s healthcare specialists was positive in 2015 partly due to having shorted biotechs. Financials is another sector with high dispersion amongst REITS, casinos, hotels and banks. Historically, the energy sector has shown less dispersion, but the oil price crash has led Candriam to opportunistically allocate to a long/short energy fund that is confident about identifying the winners and losers from lower oil prices, which will put some firms out of business while increasing the competitive advantage of others.

Fixed income, credit and multi-strategy

Candriam’s search for alpha in fixed income markets has recently lead to Asia. In response to concerns that some managers are running too many assets, Candriam’s fixed income arbitrage bucket has been re-allocated towards Asian managers that might profit from greater volatility. Two Asian managers have been added in the foreign exchange and interest rates spaces, and “they play the arbitrage between retail investors and institutional market makers.” Candriam was also an early investor in a manager that has moved to Hong Kong in order to focus on Asian markets.

Though Candriam may remain invested with some managers for many years, none of Ferrand’s investee funds should become complacent. The average of 15% turnover across 45 funds implies that Candriam could on average exit six funds per year. Strategy and manager rebalancing decisions can be made on a monthly basis. Reasons include “style drift; if their strategy is becoming a crowded trade; the assets are too high; or people are applying leverage because they cannot maintain returns with tight spreads”.

The last of these alludes to a deft strategy shift that helped the CWA strategy survive the credit crisis. In extreme conditions, the team are not afraid to cut and reverse from a long-biased to a short-biased stance. She says, “We were saved in 2007 by reducing credit due to Bear Stearns. We also entered a short credit fund and had an activist manager who was short of sub-prime names.” Other portfolio insurance trades have included opportunistic allocations to tail risk funds, though they are not a current allocation.

Candriam’s need to keep a close handle on risks being taken by funds means that they will rarely delegate the strategy allocation decision-making to a multi-strategy hedge fund, as these tend to be too opaque. “We do not know when they might have shifted from credit to equity,” says Ferrand. For the same reason, Candriam has held very little convertible arbitrage, as “we cannot predict if managers will emphasise the credit or equity buckets.” Nonetheless, Candriam does own a small number of multi-strategy funds that have strong track records of alpha generation.

Liquid alternatives and liquidity

Candriam’s alpha-dominated fund of funds return profile has historically shared the resilient return pattern of Candriam’s single-strategy funds, often performing well in difficult years such as 2008 and 2011, and reflecting the relatively cautious corporate philosophy that permeates all units. But Candriam’s multi-manager business cannot allocate to, or recommend, Candriam’s single-manager or strategy funds, and this applies right across the board – to hedge funds, absolute return and UCITS. Though Ferrand recognises how Candriam has been a pioneer in the liquid alternatives space, the CWA strategy is generally invested in offshore funds that offer quarterly liquidity. Candriam did in 2010 start a small fund of UCITS hedge funds strategy, known as CMM Alternative, that allocates externally to a handful of managers. This strategy differs from the CWA flagship strategy in that it tends to have somewhat more equity exposure than the main fund of funds. Candriam has also drawn up a ‘buy list’ of UCITS funds for an advisory client. The list of approved UCITS funds is highly selective due to the special challenges that can be entailed in running some alternative strategies in a liquid format. Ferrand is particularly conscious of the basis risk associated with using more liquid indices and sector ETFs, instead of less liquid single stocks, on the short side. She also thinks that liquid alternatives vehicles need to manage inflows and capacity very carefully, recalling how even money market funds ran into trouble and ‘broke the buck’ in 2008.

Though the flagship has not invested in products labelled as ‘liquid alternatives’, it has maintained good liquidity and in particular weathered the 2008 crisis well. Assets in the CWA strategy have come round full circle, from €350 million when Ferrand took the co-helm in 2004, to €400 million in 2015. In between, assets peaked at €2.2 billion in mid-2008 and halved to €1.2 billion by the end of that year – but not primarily due to the small losses in that year. Given its prevailing terms of 35 days’ notice for monthly dealing, the fund of funds was used as an ATM, and paid everyone in full up until March 2009. By that stage a decision was made to invoke the gate for two calendar quarters, to slow down the outflows – but not suspend dealing. Ferrand explains, “We had the cash to pay, but did not want to disrupt the portfolio by shrinking the more liquid bucket and letting the less liquid bucket expand.” Consequently, Candriam did not alter the liquidity profile of the portfolio of funds. There were a few side pockets, some of which were steadily marked down to zero, while others were monetised.

Reflecting on the crisis, Ferrand feels, “it was heroic to have paid everyone on those terms, and 2008 was our only down year in my 10 years co-managing the strategy.” Ferrand admits that managing outflows meant that the fund was less fully invested than vehicles starting afresh in 2009 might have been, which limited its ability to take advantage of QE-inspired asset repricing in that year.

Winning mandates once again

Even as financial markets recovered, and Candriam continued to deliver its hallmark steady performance, Ferrand had a new challenge to contend with: the distraction of former owner, ‘bad bank’ Dexia, and this explained why the company kept getting redemptions – until 2015. Ferrand is relieved that “the backing and support of triple-A-rated and institutional-quality New York Life is giving comfort” – and Candriam is once again winning mandates, including in its multi-manager business. “We have much to offer: we have the flagship to show our track record, we can build funds of one, and our stable team is now part of a stable company,” says Ferrand. Even during the turbulent Dexia years, the team displayed remarkable stability (as did the teams on the single-manager side). “We always had the support of management, who wanted to keep the business alive, and never cut staff, so managers recognise us as a very cohesive team,” Ferrand reiterates. Over the past decade, the team only saw three departures, and always hired replacements from inside Dexia, drawing on corporate colleagues from risk management, accounting and equity analysis. Since 2008 the team has been unchanged.

So, Candriam’s flagship, CWA, is its calling card to show its capabilities, and Ferrand echoes the growing number of insurance companies and other large institutional allocators who see alternative multi-manager approaches as an alternative to fixed income. “With interest rates so low, our return profile is similar to the bond market,” she says – but without the interest rate duration risk. This is particularly relevant in Europe, which in November 2015 had over a trillion euros of government debt demanding negative yields.

Fund of funds assets are $700 million, including long-only (where US, European, Japanese and emerging market equities are offered alongside defensive, neutral and enhanced balanced products). But, as is increasingly common in the multi-manager industry, the advisory assets are far larger at $3.9 billion. Multi-manager groups are in some cases competing with investment consultants in this space, though funds of funds have generally been building and managing real-money portfolios for far longer. Ferrand expects advisory and bespoke mandates, and funds of one, will continue to be the main driver of growth on the alternatives side, as many large institutions that need to dictate special terms do not want commingled vehicles. “With New York Life as our parent company, we are now targeting big institutional clients who might previously have been afraid of the Dexia brand name,” Ferrand enthuses, and she thinks Candriam is particularly strong in “European managers, fixed income and quant.” The Candriam ‘buy’ list contains around 80 alternative funds and 120 long-only funds.

Ferrand summarises Candriam’s philosophy: “We are not following fashions, as we want to be around for the long term, producing slow but steady performance, and constraining drawdowns. That is our DNA”. We would wager that the team will be running multi-manager money for some decades to come.

The Candriam Team

Maia Ferrand Co- Head of External Multi-management (pictured, top)

Jean-Gabriel Nicolay Co- Head of External Multi-management (pictured, above)

Christophe Chrun Senior Portfolio Manager

Pascal Cambier Deputy Head of Alternative Multi-management in Luxembourg

Jo Buyle Assistant Portfolio Manager

Yves Teszner Hedge Fund Analyst

Natalino Barbosa Hedge Fund Analyst

Jean-Marie Yao Quantitaive Analyst

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical