The challenges faced by hedge funds during the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath shook industry leader Man Group and smaller peers alike. Falling assets under management and shrinking profits brought in wide ranging operating changes and streamlining. Man’s public company structure meant it had no choice but to take its lumps while making changes in the full glare of substantial media scrutiny. Perhaps that accounts for the Group’s rapid restructuring of its fund of funds business, its comprehensive push to provide managed account solutions and then its potentially transformational acquisition in 2010 of leading equities shop GLG Partners, Inc. It’s true that hedge funds often change investments rapidly, but for what is a FTSE 100 company, the corporate transformation shows that Man executives pay close attention to messages from the market.

All of this is reflected in a rebounding share price and is welcome news for Chief Executive Peter Clarke (pictured, above), the long-serving Man executive who helped steer the company to its float in 1994, became chief financial officer in 2000 and then replaced Stanley Fink in the top job in 2007. We met at Man’s soon-to-be vacated Sugar Quay headquarters on the western flank of the Tower of London. The firm is swapping this prime river front location on the Thames for another a few blocks further west later this year. An executive with Man for 18 years after leaving Citi, Clarke has a whippet-like physique (doubtless the product of an intensive fitness regime) and shows a keen grasp of the Group’s development and operations.

New business unit

An early fruit of Man’s $1.5 billion acquisition of GLG is the creation of a new business unit called Man Systematic Strategies, which is about to begin marketing two new products to investors. “The new business is dedicated to looking at systematic trading around discretionary trading strategies,” Clarke says. “Now we have both pieces to do that. This will include product that has systematic content in different delivery formats – exchange traded funds and other formats that can deliver transparency and liquidity at a higher frequency than a traditional statistical arbitragemanager would want to give you. It is more of a quasi-institutional product. The investor base globally wants more liquidity and more transparency, and AHL lends itself to that. One of GLG’s positive characteristics is that it had managed accounts and UCITS products which can cope with frequent liquidity as well. We can now deliver the liquidity across a range of strategies. But it is important to be careful that there is real liquidity in the underlying investment. This is an important lesson from 2009.”

Another example of co-operation in the enlarged group is a move to build new structured products using GLG’s internal multi-manager fund in tandem with the momentum system employed by AHL, Man’s flagship $22 billion managed futures programme. The first structured product combining the systematic and discretionary approaches of AHL and GLG respectively is Man IP220 GLG. The link-up means that funds under management were $68.6 billion at the end of 2010, including $13.3 billion of long only money managed by GLG.

A key driver for the GLG acquisition was to add an equities business leg to the large multi-manager and commodity trading advisor operations Man had. What’s more, Man knew GLG as its fund of funds was a managed account investor in a number of GLG funds. GLG also brought a number of top executives, including Manny Roman who is now chief operating officer of the combined group and investment managers (and GLG co-founders) Pierre Lagrange and Noam Gottesman. Lagrange is overseeing all active investment management and his stewardship of the flagship GLG European Long/Short Fund saw it return over 11% annualised since 2000.

“They had investment talent and a strong product platform,” says Clarke. “We were long distribution and short content; they were long content and short distribution. There is also very little overlap in terms of geography or client base. It started from the view that we wanted something that was complementary in terms of an uncorrelated return profile with AHL in particular. We also wanted something that would have widespread appeal to investors from institutional through to retail.”

Being a listed company in the US helped since GLG’s founders had ceded ownership to public investors. “It wasn’t a situation typical with hedge funds where the proprietor was saying I just can’t give up control of my business, which is the usual obstacle,” Clarke says. “The other key thing for us was that we didn’t need to monetise anyone to take control. Usually the situation that arises in hedge fund M&A is that you can have control but you are buying out a partner and we weren’t interested in monetising someone. GLG had already had a monetising event and this made it an easier proposition.”

Growing by acquisition

Man, of course, has grown by acquisition. Typically, it has bought a minority or small majority stake, gotten comfortable with the specific fund business and then followed through with a buyout. It built up the assets of AHL over more than two decades (acquiring it from founders Michael Adam, David Harding and Martin Lueck), while adding fund of funds businesses like RMF. It also owns stakes in other managers, the most valuable being its 25% interest in BlueCrest Capital Management, acquired in 2003. Backing ex-J.P. Morgan traders Mike Platt and William Reeves looks particularly shrewd now that they have built Europe’s 3rd biggest hedge fund group with over $25 billion in assets.

When Man got into hedge funds in the mid-1980s its main business was commodities broking and sugar trading, its original activity from its founding in 1783 (see timeline). This early interest helped Man get into a growth industry on the ground floor. In those years, the hedge fund opportunity must have seemed somewhat intangible. Its float in 1994 showed Man’s adaptability and the readiness of executives to engage with the market in setting up an optimal corporate structure. It has been highly opportunistic in developing – and hiving off – businesses ever since. Even with the integration of GLG, it numbers just 2,000 employees, making it the leanest company in the FTSE 100 with a highly enviable revenue-per-employee ratio.

“I think it is part of our success that we continue to evolve as a business,” says Clarke. “We stay close to markets. If the market changes, we change. If our investors and shareholders have a different expectation we will move to meet those expectations. We have demonstrated to shareholders since we floated that we have an ability to continue to evolve quickly.”

Over the 25 years Man has built its funds business, the industry has morphed several times. In the early 2000s, the market environment was relatively benign with credit cheap and readily available. Then the world changed, shredding many business models, notably in the fund of funds sector where Man was a leading player. For all of the hedge fund industry’s fabled adaptability and ability to grapple with change, a large part of it got steamrolled. That shock is still reverberating but Man, having lost some $30 billion in assets from the 2007 peak, has adapted. It raised capital from selling off the remnants of the brokerage business, reorganised its fund of funds operation trimming overheads and then did the GLG deal to diversify risk outside of AHL while boosting research budgets for the CTA flagship by creating the Oxford Man Institute.

Equity succession in management

“What Man has shown in the 2000s is an ability to change,” says Clarke. “What we’ve done is demonstrate how quickly we can embrace change as a very significantly sized organisation. I would say that since the early stages we have been ahead of the hedge fund industry in terms of the shape you need to be, to be a long-term, sustainable investment management business. The hedge fund model we have seen in many guises has not been a very long-term one. Many hedge funds have fragmented and failed to capitalise on the intrinsic value and goodwill inherent in the business,” he says, citing Soros Fund Management and Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management. “It is a people business so it is capable of disintegration in that sense. We’ve worked very hard to create something that is much more sustainable. Part of that comes from our listing so we have equity succession in management.”

The public listing and strong cash generative nature of fund management means Man has ready access to capital across the business cycle. That allows it to invest in the business or join investors in co-ventures. Since 2007, it has read the entrails and invested more in an institutionalisation of process culminating in the restructuring of the three semi-autonomous funds of funds units into one business tied closely to managed accounts. Mistakes were made, for example, at RMF, which got caught up in a Madoff feeder fund in late 2008. But the investment performance of AHL and the liquidity of the fund of funds meant that investors were generally well served. In the changed environment of the 2010s, Man is a strong, disciplined and dependable player.

“We have strong relationships with counterparts,” says Clarke. “We are seen as a long-term credible, high quality regulatory partner. Those things become more important in a much more uncertain world. I can’t think of another investment management business, and certainly a hedge fund business, that has changed itself as dramatically and significantly as we have totry to be more relevant in 2011 to investors than the rest of the industry. Time will tell but I think we have done that extremely well.”

Roman becomes COO

The takeover of GLG hasn’t just reshaped Man Group’s funds offering. It has also reconfigured the company’s management structure and seen Manny Roman, (who was a joint CEO of GLG with Gottesman), slot into the newly created post of chief operating officer. In practice, the investment management function, including portfolio managers, and the sales force, who communicate with investors, and some governance functions, report to Clarke. Roman is responsible for product structuring, operations and technology. This joined-up approach replaced what had been historically a very fragmented operating template at Man.

“With Manny being in the middle as COO we have a clearer take of the return stream that the investor expects and the salesman sold, and the return stream that the investment professional, the PM, generated at the other end,” says Clarke.

“Manny understands investment management from his time in the derivatives business at Goldman Sachs. He understands the CTA business, he understands the client requirements and he understands that there is a business in the middle that has to be joined up, and he has a very clear mandate to do that. Manny is a great operational person, very capable of holding his own at any level of detail across the firm and of course that is a great attribute to our business. Also, in the context of integrating GLG it is very useful to have the former joint CEO in a position to look across it all – he has visibility right the way across and that is a reassurance to me and to the GLG teams that there is someone at a very high level that understands the way they work as well.”

Clarke’s key reports include global head of sales Christoph Moeller, AHL head Tim Wong, Luke Ellis, head of multi-manger and Pierre Lagrange, who continues to head investment management in the GLG business and Stephen Ross, the general counsel. The head of human resources Michael Robinson and finance director Kevin Hayes round out Clarke’s reports and the entire group forms Man’s reconstituted executive committee that runs the company day to day.

In New York, Gottesman runs a team overseeing the Global Opportunities Fund that allocates internally across GLG strategies. It is this product that is being combined with AHL to offer investors customised, structured return streams. With GLG’s range of strategies it means Man now has the capability to source internally what had been sourced externally to pair up other return profiles with AHL in structured products. Gottesman is responsible for running this core franchise, building up the New York-based investment management capability (which currently has about 20 portfolio managers) and being a high level contact point for clients.

Growing AUM

Over nearly two decades, Clarke has seen Man expand from small hedge fund foundations to become a global leader. He is careful to point out that growth in AUM is a consequence of success rather than an objective. “If we are phenomenally successful and continue to expand our capability which includes long only, right the way across hedge and CTAs there is no reason to suppose we won’t become a $100 billion firm,” Clarke says.

The key to expansion is offering high quality hedge fund return streams where Man can deliver something unique to investors. “We want that to be across all of the strategies where we think we have an edge,” Clarke says. “There is still more we can do in credit. There is still more we can do in that gap between systematic and discretionary. We have the capability of delivering a return in broadly whatever format investors want wherever they want it; totally transparent or not; UCITS or not; open ended or not; structured or not. I think that everyone will find some piece of that of interest to them.”

In addition to flexibility, Clarke thinks Man will benefit from the increasingly imposing regulatory environment. Certainly the firm’s scale, operational infrastructure and financial foundations make it a highly ranked counterparty.

“What we see from the regulatory environment is an opportunity to take people out of investment banks, whether it is Goldman Sachs or elsewhere as they unwind from the principle investing requirements of Dodd Frank,” he says. “What we see is an environment where the banks are tending to open up their architecture and there is chance to get into their distribution system on a more equal footing because they haven’t got a house product. Lastly there is a regulatory headwind in terms of cost, burden of compliance and client emphasis.”

Regulatory burden

Of course that regulatory burden is something Man has dealt with for decades. Indeed, having the infrastructure and experience of dealing with regulators may confer an advantage on Man for some time. In both Taiwan and Singapore, for example, Man is the first manager to get permission to sell an open ended, onshore CTA product to both retail investors and institutions.

“For this period of regulatory caution in the face of uncertainty in the world it is a distinct advantage to have those regulatory relationships and that credibility,” says Clarke. “Historically it has always been a bit of a headwind for us because no one else had to hold capital and we always did. But for a period it will be a tailwind. No one here, for example, has been affected by the Alternative Investment Fund Manager Directive. It has not been an issue for us.”

At a time when doubts surround the UK’s place in the international financial pecking order, it may be surprising that Man has, in effect, doubled up on London by acquiring GLG. The senior portfolio managers of BlueCrest and Brevan Howard, after all, abandoned London for Geneva in 2010. Clarke, for his part, expresses confidence that London will continue to be an important centre in the global hedge fund industry, albeit it with an important caveat.

“We have been here for 227 years and we are not in a rush to leave,” Clarke says. “However, it is true to say in recruiting, particularly young people from abroad with no intrinsic ties to the UK, that London isn’t as attractive as it used to be. That is a combination of uncertainty about the regulatory regime and certainty about a particularly high personal tax regime. The real threat is that longer-term London is not a place where new talent is keen to locate compared with Switzerland, New York or Singapore.”

An enduring business model

When Clarke, a lawyer by training, joined the then ED&F Man in 1993 from Citibank after a stint doing M&A he had a remit to find a business model to take the firm into the future. The options were straight forward: trade sale, capital injection or initial public offering. The firm had been owned by its employees, but the directors realised that it needed to migrate from a partnership structure to a corporate one.

From the outset Clarke realised that an IPO was the best solution. “Man had the experience before I was involved of having a significant stakeholder in Klaus Jacob of Jacob Suchard, which was then bought out by Philip Morris, which had no strategic interest,” he recalls. “That trade allegiance was not seen to have added very much. For those reasons an IPO carried the broadest support in the organisation.”

As the first hedge fund group to float, Man got a jump on the industry. But listing alternative asset managers on exchanges remains relatively uncommon. This changed briefly in 2006/2007 when, among others, Partners Group, Absolute Capital, BlueBay and GLG as well as Och Ziff and Fortress Group secured IPOs. Since the credit crunch the IPO window has remained firmly closed. While it is undoubtedly true that the trail Man followed may not suit the asymmetric power structure of many hedge funds, the difficulty of a firm surviving beyond the founding partners is an issue that confronts the industry to this day.

Riding AHL

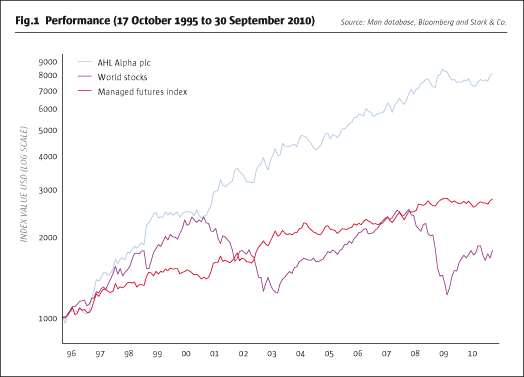

Many factors have been pivotal to Man’s transformation into a hedge fund giant, but none more so than AHL, launched in 1986. As some CTAs have fallen by the wayside, AHL has kept growing and is now coming out of its longest ever drawdown with a 14.8% return in 2010. Investors will hope this presages a strong upturn for the next few years after AHL earned bumper returns in 2008.

“Many of the CTAs get to a reasonable size and then start going wrong,” says Clarke. “That hasn’t happened to AHL for several reasons. The first is that AHL was taken under full control (ahead of the IPO in 1994). That allowed us to create a management succession. Since the sales force sat outside of AHL and sold other things, we added other exposures to reduce the fairly volatile CTA ride for investors.”

Having capital meant Man could invest in research and development, something it did for many years before funding the Oxford Man Institute in 2007. This involved finding new ways of trading markets via algorithmic functions and of indentifying signals more effectively. More recently, the order execution function has evolved to optimise trades and reduce risk.

“We’ve put a lot of capital into each of those areas, particularly on order execution, which is the defining constraint for trend following,” Clarke says. “It was helped by the fact that we owned a brokerage business, the world’s largest listed derivatives and clearing business. We were therefore very focused on how you trade markets, how you do that efficiently, who the best counterparts are, where to find the best rates, whether to voice broker or electronic trade in any market. We got that end of it absolutely better than anybody.”

Few limits on size

Clarke sees few limits on the size AHL can reach or indeed on how big the CTA sector can become. Assuming new markets develop and capital flows in to provide healthy liquidity, there is little reason to expect growth to cease. Indeed, the track record in terms of investment performance and honouring redemptions over 2008/09 means, if anything, that CTAs are among the hedge fund industry’s most viable portfolio management strategies.

“Going back to 2008/09 everything correlated except for the big, deep derivatives markets,” says Clarke. “Macro and CTAs did well because they continued to trade through those markets. If you can’t trade it doesn’t matter whether you have the right idea or the wrong idea – you’re stuck. If you can continue to trade you can take advantage of opportunities. The futures and options markets have natural participants in terms of sellers and buyers of risk. In comparison, there is almost no reason why you have to buy an equity. But in futures, investors are always trying to hedge interest rates or input prices and people will take the other side of that. It is a much more natural two way market and liquidity is more inherent than in the cash market.”

Funds of funds evolve

In 2009, Clarke amalgamated the separate funds of funds businesses into a new structure now rebranded simply as Man. The new aim was to use managed accounts to provide investors with a safer way of investing in a diversified set of underlying hedge funds. Man saw that managed accounts could improve risk management by allowinga top down look into positions that would allow its managers to police aggregate portfolios for clients. Once the use of managed accounts had increased, Man realised that they made it possible to be much more dynamic in its allocations, allowing subscriptions and redemptions to occur much more quickly.

“That sort of dynamic approach to investment management we found very useful,” Clarke says. “We thought it would become quite an interesting tool for investors to satisfy custody, control and liquidity visibility. I think this is a proposition that funds of funds can use to add value. We can produce something that is very compelling to large allocators that don’t have the infrastructure to police, risk manage and do due diligence on hedge fund investments. It doesn’t have the same margin as investment management, but it is the way funds of funds can build high conviction, more transparent, highly focused portfolios.”

Clarke thinks funds of funds delivering an index-like return through a co-mingled fund have a future perhaps with smaller institutions and corporate pension funds. However, big investors like sovereign wealth funds and state pension providers will be buying exposure to, say, a macro or bond hedge or inflation theme related to the needs of their overall portfolio.

“This has value for investors and is a long-term viable business for funds of funds,” says Clarke. “But that is a different proposition to getting an index-type return from the hedge fund community. There are still buyers but that is a much smaller pool to be fishing in than it used to be. To fish in the bigger pools of assets you need to be adding intellectual overlay for portfolios and be able to deliver those in an efficient and economic way. That’s why there is a scale requirement to doing this.”

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical