Obviously the big brains behind some of the leading commodity trading advisors or CTAs see it differently. In this respect, Tim Wong the CEO of AHL, Man Group’s $19 billion dollar managed futures flagship, is typical. Joining AHL in 1991 after graduating in engineering from Oxford, Wong has worked his way to the top. It’s no surprise, then, that the algorithms and other processes AHL uses pose little mystery to him.

Nor do investors seem bothered. The overall market share held by CTAs in the hedge fund space is at all time highs. Barclay Hedge estimates that around $328 billion is invested in CTAs, up over 50% since 2008. The reasons for this are straight forward: CTAs are very liquid, risk is documented and managed, while performance, especially through the most acute phases of the credit crisis in 2008-09 was good.

Low profile

Despite running one of the world’s biggest investment strategies, Wong keeps a low profile and features rarely in interviews. Meeting at Man Group’s airy new Thames-side headquarters our conversation ranges from the persistence of market trends and the impact of technology to the enormous new opportunities on the horizon in China’s futures markets which are expected to become more liberalised in coming years. To begin with, Wong offers a broad overview of what AHL does.

“We try to do something sensible by examining reasonably stable, long-term kinds of correlations and expected returns, while putting this all together with a common sense look at the liquidity of the markets,” he says. “Perhaps because of my engineering background, we focus on how a market actually works. We try to find particular trading rules rather than try to build something that is like a super-complicated times-series forecasting model. We use the technology and systems to test and implement our ideas better. At the end of the day it’s a human game. There’s not much point in building a fancy, complicated mathematical model when that’s not the way the market actually works.”

Recruitment to AHL

How Wong found AHL and ED&F Man as it was then known is serendipity personified. A small notice had appeared in The Times advertising an opening at a company with young, dynamic people using science to trade financial markets. “It got my interest,” recalls Wong, noting the information about the company was sketchy in the extreme. “It was by chance almost that I saw the advertisement. I think that was quite a good break, really.”

Wong found the transition to AHL from the engineering department straight forward. The goal in the work place and in the academy was the same: just solve problems.

“As an engineer, your tools and the techniques that you learn are just means to helping you solve problems,” says Wong. “So when I arrived at AHL senior people would have a rough idea about the way of trading the market and we’d take data and computer time to see if it could be made to work.”

A particular mentality

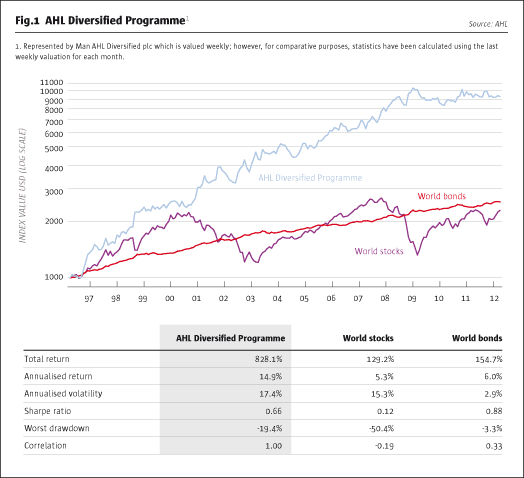

It is sometimes commented that it takes a particular type of person to run a CTA strategy. During periods of market mania like the dot.com boom, managed futures will usually underperform equities, often by a substantial margin. During less trending markets, CTAs will often be in drawdown. This is the case now with AHL. Even though it is up 1% in 2012 and displays average annualised returns of 14.9% (See Fig.1 and Table 1), it remains below its high water mark. Moreover, AHL is enduring, along with many other CTAs, its longest ever drawdown.

But could things be different this time? After all, the models used by CTAs originate in the market conditions of the 1970s and 1980s. With market conditions post-2008 completely changed, does trend following risk becoming obsolete?

There are several reasons why this is unlikely to happen. For one thing, the models managed futures strategies deploy are continually being discarded for new ones. In short, a process of creative destruction occurs. More importantly, the market inefficiencies that CTAs exploit, while long recognised, continue to persist. In addition, human behaviour and markets tend to demonstrate observable patterns.

Extracting returns

“I’m not saying the inefficiency will be there for ever and ever,” says Wong. “But to me it is quite important that, first, this phenomenon has been around for a long time; and second, that extracting the returns from it is much harder to do than you might think. We really haven’t seen a lot of evidence that the inefficiency has got eroded, apart from the diversification as markets have converged more. The result is we need to hunt for different bets to put on now.”

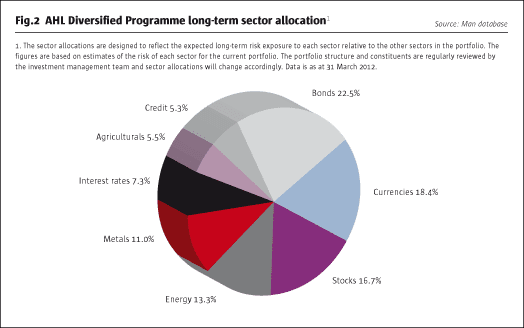

The massive growth in the number of futures contracts spanning different asset classes (See Fig.2) and volumes in those contracts has been a key factor in helping CTAs expand assets, while remaining highly liquid. Far from this process running its course and bumping up against capacity limits, it seems that future developments might presage a new round of growth. For the top seven managed futures firms – Winton, AHL, BlueCrest, Transtrend, Tudor, Aspect and CFM – managing around $100 billion, this could be the key to the next phase of expansion.

The question of where a good chunk of the growth in futures contracts might come from has a straight forward answer: China. Wong, born and raised in Hong Kong before immigrating to Britain to attend Oxford, is intensely aware of the opportunities that the liberalisation of Chinese futures trading offers. The Chinese authorities are planning the launch of a crude oil contract on the mainland that would be open to foreigners to trade. How the contract will be structured and whether it will be priced in RMB or dollars remains undecided.

“The answers will become clear before too long,” says Wong. “China is opening up pretty quickly. Its influence on the global market, apart from generating some growth, has been a little bit limited. If you talk to the Chinese people they say they don’t have enough pricing power to influence the global market. This is something China wants to address – the need for more pricing power, particularly over the commodities that they rely on.”

The opening of Chinese futures markets to the world will have a big impact on managed futures trading. With China now possessing a larger futures market by volumes traded than the US, it means the liquidity added to global futures markets will be huge. Even more significant is how China will offer a plentiful source of diversification at a time when that is desperately needed.

“Over the next few years China will be an extremely important chapter for the CTA universe,” says Wong. “I’m not saying trading with them will be automatically easy. But AHL has always been one of the first to trade pretty much all the new markets, so hopefully we’ll be one of the first funds that can benefit from that.”

AHL will need regulatory approval to be involved in the new Chinese crude oil contract. But it is well placed to obtain permission. It already has a trading desk in Hong Kong (with other front office functions run through Man Group) and the fund itself was the first CTA to be licensed for distribution to investors in Singapore. The group’s business model of operating onshore and offshore globally means that it has a culture of complying with a wide range of regulatory regimes.

Correlation heightens drawdown

Getting right of access to trade the currently off-limits Chinese futures markets could be highly positive for AHL. Certainly, its drawdown has been exacerbated by the heightened correlation that has seen prices in different asset classes across the G10 markets get overwhelmingly driven by the euro zone sovereign debt crisis.

“When you lose diversification in the G10 markets it’s extremely difficult to make money,” says Wong. “It doesn’t mean that you won’t make money, but your returns are very low. The strength of our models is that they can be applied to a wide range of markets. Therefore you can rely on that diversification to get the Sharpe ratio higher. But in this environment even though the Sharpe ratio is still positive, it takes longer to make money.”

It is notable that of the 300 different instruments AHL trades around the world, the portfolio outside of the G10 behaved with less correlation. That diversification helped generate performance for the broader programme but not enough to offset the G10 correlation.

“If you focus on the (non-G10 markets) over the last few years, they have generated performance over the last few years and with a reasonably similar Sharpe ratio to before,” says Wong. “It highlights how this extremely Eurocentric and debt-centric environment is causing problems.”

Expanding diversity

The growth in emerging markets and rising liquidity means that asset class diversity is expanding for AHL and other CTAs. But G10 markets still remain the biggest part of the investment universe. So with those markets behaving with less dispersion, AHL is diversifying by adding different types of models rather than new asset classes. Allocating more to new models is expected to go further this year and during 2013.

One thing the new models do is trade intra-asset class. This involves looking at the price relationship of different contracts in a particular market but not with respect to a trend. Other models try to make use of different factors to forecast a market, rather than using just price trends. Shorter-term relative value type trading has also been developed. In addition, some models look at what can be picked out on the yield curve in trading fixed income instruments.

“We are doing a variety of different things which are not trend-following,” says Wong. “We have done the diversification in terms of using different time-frames in trend-following so there’s not much more diversification you can get there. So we have sought to diversify by finding different types of models. Having said all that, clearly, momentum-trading will still be a large part of what we do, but the new models will help.”

Examining casual relationships

With currencies, for example, casual relationships with other asset classes are being examined. Looking at asset flows may also yield insight into the price movement in a national bond or equity market. It could be possible, for example, that price movements in those markets may provide information that leads the currency rather than its movement being just the product of a trend.

New models are also being deployed on commodities. The relationship of a commodity price curve and the volatility of a calendar-spread is one focus. If that can be forecast accurately it could be possible to make money off the calendar spread as well as the more straight forward price movement. In all of these things Wong says AHL is trying to be more orthogonal.

“The idea is you can have models that actually complement the trend-following model, but don’t take away from it,” he says. “Ultimately, a momentum model has some very nice characteristics. It tends to be uncorrelated to investors’ traditional portfolios. In a sustained financial crisis, it tends not to have a very sharp tail. You want to preserve that and not jeopardise that relationship. So we are trying to find something that complements the trend-following model, but doesn’t overwhelm it.”

Oxford Man Institute

The work on trading models is one product of the research being done at the Oxford Man Institute of Quantitative Finance. For AHL, this search for alpha in innovative trading models also extends to research in portfolio construction.

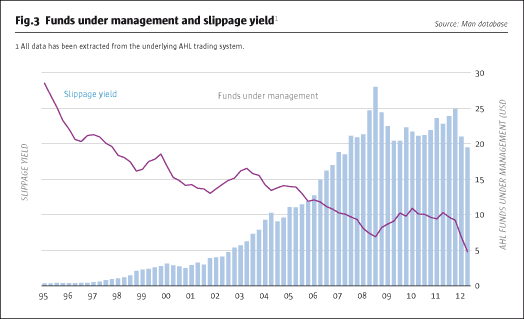

Another focus of the Oxford Man venture is risk management. The aim is to analyse ways to measure risk and manage correlation. A third area of research is execution and finding more efficient ways of getting trades done in the market. Here AHL monitors execution and broker transactions to assess slippage on trades, which has declined over time (See Fig.3).

For many years, the programme has made continual adjustments to algorithms to get trades done at best cost. Recently AHL introduced an ultra slick, proprietary ‘virtual trader’. In a wide screen demonstration, streams of colour coded FX pairs bid/offer prices from dozens of banks are displayed showing price competition and the fill points where different portions of a currency pair get settled.

“It is a big step forward for AHL to know what the best algorithms are and to improve them,” says Wong. “That is actually quite a big research effort. A large part of it is about the plumbing and trying to connect your algorithms to exchanges, trying to understand how the allocation algorithms actually work and trying to understand the market microstructures and how all those things actually hang together. Once you’ve understood that, the solution becomes pretty obvious and we have benefited from research that Oxford academics have done.”

A risky juncture

Over the past five years constant research and innovation has gone into risk management. The euro zone crisis is merely the latest spectre to hang over markets. Whereas counterparty risks with banks were once virtually unthinkable, now contingency plans to deal with a systemic bank crash are very much mapped out.

“We run a scenario where if something does happen, then we want our models to be reacting in a reasonable fashion,” says Wong. “Secondly, we also want to make sure that if something really big happens, say to a counter party, we have enough redundancy to be able to shift our positions. Five years ago that wasn’t on our radar. We assumed basically that as long as the futures markets are clearing that the system is well capitalised and that the top-tier banks we dealt with were basically too big to fail. You simply can’t make that assumption anymore.”

AHL has enhanced the risk management function and heightened its presence in the investing programme by appointing Douglas Greenig as chief risk officer with Matthew Sargaison, currently CRO, moving to become chief investment officer. An early task for Greenig is looking to quantify and factor different scenarios. A simulation might consider what would happen in the case of an intervention to cap some of the risk in the portfolio and what the impact on performance might be.

One area where research has been particularly fruitful is using higher-frequency data to forecast volatility. That can improve risk-management. What’s more, if volatility can be more accurately forecast, it can then be traded more directly.

In this area, Neil Shepard, Research Director of the Oxford Man Institute and Professor of Economics, has given some impetus to AHL revising models run in its main programme. This has involved the use of a small volatility trading model which trades options and tries to capture volatility mismatch. Man has also utilised the research in its development of a tail protection product.

Volatility wobbling

Analysis of the 1988 corn bull market showed that volatility can be estimated by using past volatility. Yet the paradox of volatility and its relationship to risk is that at times when markets are static, it probably doesn’t mean that there is actually no risk.

Events like sterling crashing out of the European Rate Mechanism in 1992, the spring 2010 ‘flash crash’ and the Japanese tsunami in 2011 all unleashed extreme volatility. In each case, the volatility came out of nowhere, bringing about extreme reactions, showing that risk in the markets was much greater than anticipated.

Post-sterling’s ERM ejection Wong and colleagues at AHL began to calculate applied volatility and forward-looking volatility as well as historic volatility. The calculations and research have sought to better calculate when a ‘normal’ regime has been re-established.

“What we have done, first, is modify our existing model,” says Wong. “But at the same time we have looked to use higher frequency data when we can. Using high-frequency data to try and estimate volatility gives us the ability when something happens to react pretty quickly.”

Take the Japanese tsunami of March 2011. If a programme only has a handful of data points it can’t really judge whether the extreme reaction in the market is over a few days after the event. Assume, instead, every tick in the market has been monitored every single minute. A few days after the disaster when the market has fallen substantially the programme is able to respond more quickly and get back to the ‘correct’ regime.

Institutional investors

The research and innovation at the heart of AHL is increasingly being funded by the allocations of institutional investors. Over the past five years, they have increased their allocation to hedge funds, sometimes through tentative steps and other times through major investment policy changes. Data shows CTAs have done better than most other strategies in terms of attracting new investors. This is expected to continue in the future as institutions look to diversify their traditional portfolio allocations beyond equity and bond holdings.

“What you’re seeing is just the tip of the iceberg,” says Wong. “The current market environment has slowed the investment process of institutions in terms of getting into anything new, even though they have decided it’s the right thing to do. When the market environment is a little bit more certain, I think there is quite a large potential influx of allocations to alternative investments in general.”

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical