Attempting to reduce overall management fees is a very important component of managing a portfolio of hedge funds or private equity funds. As a first step in this direction, a significant percentage of institutional investors have long since moved beyond funds of funds, investing directly in underlying funds and thus eliminating an entire layer of fee drag. As the next natural step in this dance, many of the same institutional investors have taken advantage of their few meaningful strengths, namely size and long-duration capital, to negotiate lower fees for writing larger checks or accepting longer lock-up periods.

Going one step even further, some institutional allocators have made notable commitments to start-up and emerging managers, securing additional discounts and often economics for providing seed capital and accepting increased business risk.

Worth noting to this point in the evolution of this back-and-forth relationship is that fee breaks have never really come for free! In almost all cases, investors have been required to actively adopt some change or compromise for the price discount. For example, going direct may reduce above-the-line investment fees in exchange for an (admittedly far smaller) increase in below-the-line investment administrative expenses required to staff up, as well as creating more decision risk for the investor. Locking up for longer time periods creates more illiquidity risk, funding earlier-stage managers creates more business risk, and so on.

In these cases, institutional investors have calculated that the benefits from the discount outweigh the costs or increased risks associated with it. Ostensibly, the managers have performed a similar cost/benefit analysis as well.

Most limited partnerships have complicated fee structures, and negotiations occur across multiple axes. In my experience, achieving discounted terms on the management fees is an easier row to hoe than bargaining for reduced incentive fee terms. Diving into the cost/benefit analysis in Table 1 elucidates why this may be the case, and highlights why management fee concessions should indeed remain a preeminent focus for LPs during legal negotiations.

Let’s assume a simple scenario where a fund charges a standard 2% of NAV as management fee and 20% of returns after the management fee, and we’ll ignore all other administrative expenses and fund costs. Attempting to price the impact of a discount to the management fee versus a reduction to the incentive fee requires some assumption of baseline returns. For example, if the manager is willing to provide a management fee rebate of 50 basis points (Discount 1) or a performance fee reduction of 5% (Discount 2), an investor should be indifferent to these changes at an average gross return of 10%. Total fees work out to be 3.2% in either fee structure. (Investors should also take note that since performance fees are charged on after-management fee returns, absent a hurdle rate, 20% of a 50 bps discount goes right back to the manager on the back-end anyway!) However, when underwriting such potential fee discounts, both GPs and LPs may in fact assume different probability distributions for return assumptions. Investment managers are on average over-optimistic about the return potential of their investment strategy (not unlike the average entrepreneur, average sell-side equity analyst, and average economist).

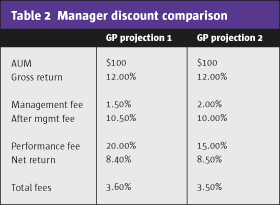

When a general partner prices the impact of a reduction in incentives versus reduction in flat fees, they may well determine that at their baseline returns (we will use 12%), reducing the performance fee from 20% to 15% is more costly than a management fee concession from 2.0% to 1.5%, as demonstrated in Table 2. Hence, they would prefer to offer the investor a fixed discount given their view of what is most likely to occur.

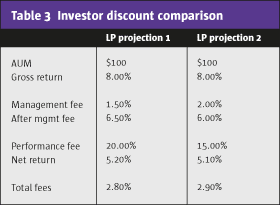

On the other hand, investors tend to be more skeptical and more cautious in setting their return expectations. A limited partner may decide that base-case scenario returns of 8.0% are more realistic, perhaps due to increases in AUM at the manager or because of other factors leading to erosion in returns over time. At this gross return level, the fixed fee rebate of 50 bps is superior to the incentive fee reduction, as it results in slightly higher net returns, as shown in Table 3.

Given that most limited partners want to ensure they are paying lower fees, certainly across lower net return scenarios, and are more likely to be able to justify higher fees if higher returns accompany them, this cost/benefit analysis makes sense. Furthermore, to the extent that the manager also is incentivised to generate higher returns (hopefully mitigated by their desire to prevent losses on their own personal investments in the fund), this represents a strong alignment of interests.

Fee negotiations should always be focused on ensuring not only the return stream comes at a reasonable cost, but more importantly that the fee structure actively incentivises desirable behaviour from the general partner. Rather than purely minimising explicit cost and dancing around alignment of interests, limited partners need to do a better job of thinking like a true partner and getting fee terms in line with intended outcomes. Next on our list of dance tracks is an agenda of normalising the crystallisation of performance fees realisable to the general partner with the lock-up and liquidity terms of the limited partner. In this two-step, it shouldn’t be realised capital gains to you if it can’t be realised capital gains to us.

In the words of the immortal Lewis Carroll, won’t you join the dance?

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 104

The Discount Dance

Negotiating lower fees requires a delicate balancing act

CHRISTOPHER M. SCHELLING, DIRECTOR OF PRIVATE EQUITY, TEXAS MUNICIPAL RETIREMENT SYSTEM

Originally published in the May 2015 issue