The principal aim of the OECD project on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS”) was to tackle perceived aggressive tax planning by multinationals. It was not aimed at hedge funds, private equity funds, real estate funds or other alternative investment funds (“AIFs”), yet they find themselves impacted. In particular the OECD and its member governments have used BEPS to revisit how companies claim relief from double taxation on income and gains arising in the “source countries” in which they operate and invest. The upshot is that such tax relief may be denied if obtaining that relief is considered by those source countries as being one of the main purposes of establishing a company in the treaty claimant jurisdiction. AIFs operate and invest internationally, so the ability to benefit from international tax treaties is critical. A key principle underlying collective investment is that the investors should not be subject to additional taxation beyond what they would have incurred through investing directly.

Accordingly, it is important that an AIF be entitled to rely on double tax treaties in the same way that their investors could have if investing on their own. Otherwise these investors could be subject to an additional layer of tax because of investing collectively, which would undermine the rationale and economic basis for the collective investment.

Double tax relief

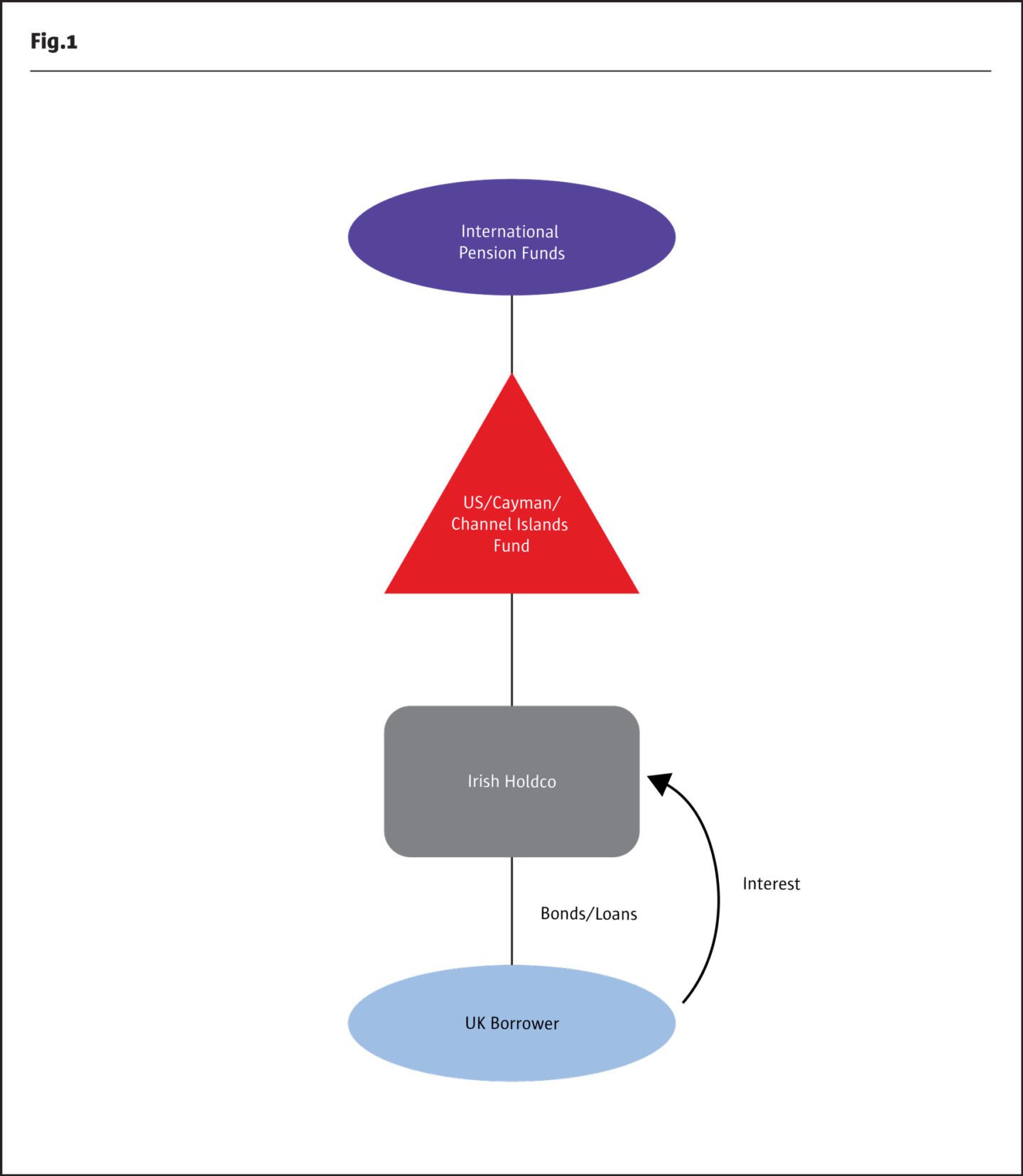

When an AIF receives overseas income (typically dividends, interest or rent, etc) or makes a gain on disposal of an underlying asset (typically shares, debt or real estate) a tax may be imposed in the source country on the income or gain. Depending on the asset, an AIF may invest through a holding company (“HoldCo”) in order to provide investors with legal, regulatory and tax benefits. If there is a double tax treaty between the source country and the jurisdiction of the AIF or Holdco, the tax on income or gain may be reduced. Take a structure like Diagram 1 below. A UK withholding tax can apply to the payment of interest from the UK to a non-UK person but the treaty between Ireland and the UK (the “UK/Ireland Treaty”) gives full relief to an Irish recipient.

BEPS and the OECD Multilateral Instrument

The BEPS project culminated in a series of “Actions” and made certain recommendations regarding double tax treaties in Action 6. Countries could adopt a principal purpose test (“PPT”) or a limitation of benefits test (“LOB”) or a combination of the two to limit the ability of a company to benefit from a tax treaty where there would be abuse of the treaty. These recommendations are now being implemented through a legal instrument which over 70 countries have signed (the “OECD Multilateral Instrument” or “MLI”). Under the MLI procedure, those countries have given the OECD their choices of PPT or LOB for each bilateral tax treaty they are party to. Depending on what the other party to each treaty chooses, a LOB or PPT will be automatically inserted into that treaty. It means that potentially many hundreds of double tax treaties worldwide will be automatically amended without the need for each to be renegotiated individually. Most countries have made their choices and, in general, it can be said that the PPT is the default option, with the LOB applying in a small number of cases (although it should be noted that the US adopts the LOB test). Accordingly we focus in this article on PPT.

Principal Purpose Test

The PPT will deny a treaty benefit (such as a zero or reduced rate of withholding tax) if it is reasonable to conclude, after considering all facts and circumstances, that obtaining it was a principal purpose of any arrangement or transaction that resulted directly or indirectly in that benefit.

For example, the UK and Ireland have both chosen PPT for the UK/Ireland Treaty. This means the treaty exemption from 20% withholding on payments of interest from the UK to Ireland will not apply if the UK considers that one of the principal purposes of the arrangement was to obtain such relief. Though some treaties already have a PPT-like test, the introduction of the PPT through the MLI and future guidance is bound to affect existing interpretations. For most treaties it will be entirely new.

PPT and EU law

Some commentators consider that the PPT may have more limited application in the EU because EU countries need to abide by EU law (as interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European

Union (“CJEU”)), which restricts the application of anti-abuse provisions to “wholly artificial arrangements” without economic activity or substance. The European Commission has stated in a recommendation dated 28 January 2016 that EU Member States should limit the application of PPT in their tax treaties to arrangements or transactions that result in tax benefits and do not reflect genuine economic activity. The recommendation reflects CJEU jurisprudence on abuse of law such as Cadbury Schweppes and the recent Eqiom SAS case where a PPT-like test in France was ruled to be contrary to EU law because it failed to include an objective test focused on wholly artificial arrangements that do not reflect economic reality. This overlay and added protection of EU law will mean, we expect, that investment in EU assets by AIFs will continue to be done by holding companies in long standing and well-regarded financial centres in the EU – primarily Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. It would be helpful if the EU approach was also adopted by the OECD (ie using the PPT to target artificial and contrived arrangements).

PPT and AIFs

The PPT has been criticised in its application to AIFs. Firstly, it turns on the subjective interpretation of each source country, which means it will be difficult to achieve consistency of application. Secondly, the test appears to ignore the ultimate investors – very often pension funds and other institutional investors located in countries with double treaties (although the useful subsequent OECD guidance, discussed below, did cite this as a helpful factor in considering the application of the PPT test). It therefore potentially does not respect the principle of tax neutrality for investment funds. (This, as already noted, is that the investor should not be subjected to an additional layer of taxation at fund level and thus penalised simply because they chose to invest collectively rather than individually.) Thirdly, it has an unfair effect on majority investors. An investor who may be entitled to treaty benefits if they invested directly may be adversely affected if a minority of investors in the AIF were not so entitled.

CIVs vs non-CIVs

The OECD has provided draft guidance on the application of PPT to funds. This guidance makes a sharp distinction between collective investment vehicles (“CIVs”) and any other fund, including an AIF, which they term a non-CIV.

In brief, the OECD consider that CIVs should be eligible for the benefit of tax treaties on the basis that CIVs are defined as being widely held, hold a diversified portfolio of securities and are subject to investor protection legislation. The OECD considers that these features mean there is less likelihood of tax treaty abuse with CIVs than non-CIVs.

Of course, the difference between CIVs and non-CIVs is more apparent than real. Many non-CIVs are subject to investor regulation and are widely held. Moreover, according to Preqin’s 2016 Global Hedge Fund Report, a significant amount of the capital invested in hedge funds (42%) comes from private and public pension funds (so are in effect “widely held”), just like a CIV. The other investors in hedge funds are predominantly sovereign wealth funds, endowment plans, asset managers, banks and insurance companies who themselves also hold their investments on behalf of multiple investors, so again in our view could be considered “widely held”.

The OECD and its member governments have two main concerns in relation to non-CIV funds: firstly that such funds may be used to provide treaty benefits to investors who are not themselves entitled to treaty benefits; secondly that investors may defer recognition of income on which treaty benefits have been granted.

OECD Guidance for CIVs

In 2010 and before the BEPS project, the OECD published a detailed report on the granting of treaty benefits to CIVs (“2010 CIV Report”). It confirmed that CIV funds should be granted treaty access in their own right provided the CIV fund is a ‘person’ and a ‘resident’ of the State in which it is established and the fund managers have discretionary power to manage the fund assets on behalf of investors. The conclusions of the 2010 CIV Report were reaffirmed in the BEPS Action 6 Report 2015.

The report also provided that, if a State was concerned about treaty abuse, a number of optional provisions could be considered when negotiating or renegotiating its treaties. The favoured approach was to treat a CIV as a resident of a Contracting State and the beneficial owner of its income, at least to the extent that its investors would themselves be eligible for benefits from the source country, rather than adopting a full look-through approach.

OECD Guidance for Non-CIVs

On 6 January 2017 the OECD published for comment three real-life example scenarios to guide application of the PPT for non-CIVs: a regional investment platform, a securitisation company and a real estate fund. A modified version of these was added to the draft update to the OECD Model Tax Convention. While it will ultimately be up to each revenue authority how they interpret and apply the PPT, the final OECD guidance will be an important reference point and is understood to be effectively binding on the revenue authorities in those countries who are not part of the MLI process. We also expect it will form part of the analysis by national courts.

The regional investment fund example is the most relevant for AIFs. In that example, the OECD commentary outlines the case of an institutional investor established and regulated in State T (“Fund”) which establishes a company in State R (“RCo”). RCo acquires and manages a diversified portfolio of private market investments located in countries in a ‘regional grouping’. State R was chosen mainly for ‘the availability of directors with knowledge of business practices and regulations, the existence of a skilled multi-lingual workforce, State R’s membership of a regional grouping and use of the regional grouping’s common currency, and the extensive tax convention network of State R, including its tax convention with State S which provides for low withholding taxes. RCo employs a management team to review investment recommendations from Fund, approve and monitor investments, carry on treasury functions, maintain RCo’s books and records and ensure compliance with regulatory requirements in States where it invests. The Board of RCo is appointed by Fund and is composed of a majority of State R resident directors with expertise in investment management, as well as members of Fund’s global management team. RCo pays taxes and files returns in State R. RCo proposes to invest in State S. The withholding on dividends paid from State S to State R is 5% whereas the withholding on dividends paid from State S to State T is 10%. In making its decision whether to invest in State S, the existence of the treaty between S and R was considered. However, in view of the above non-tax reasons for establishing RCo in State R, the draft commentary states that it would not be reasonable to deny the benefit of the treaty.

Commentary on the OECD Guidance on Non-CIVs

In practice most AIFs are Cayman or Delaware partnerships that have a range of institutional investors including pension funds. AIFs will mainly be managed and controlled by their board of directors or general partner where they are domiciled. However, to provide investors with the best expertise in a particular strategy they will often delegate day-to-day investment management to an expert manager in a major financial centre with back office functions outsourced to wherever is most efficient.

Moreover, though PPT is about ‘purpose’, the example suggests that AIFs will need to increase ‘substance’ in the jurisdiction of the AIF and/or HoldCo. If trading companies should be taxed where their profits arise, then ‘substance’ has something to bite on. For an AIF whose management takes place through a manager in a major financial centre it is not as easy to achieve a change in substance.

Substance

Nevertheless, many AIFs are aware of the importance of showing the non-tax factors in their structure to strengthen their case in the event of any challenge from source countries to future claims for tax relief. Typically this includes concentrating as much of the middle and back office operations in one suitable HoldCo jurisdiction as possible, and, in some cases, moving one or more senior investment executives with real deal experience to that jurisdiction. Ireland has become a popular choice in this regard, given the size of its financial services industry and economy generally. Several AIFs in our experience have located personnel in Ireland, and indeed relocated operations out of other jurisdictions. This is coupled with the “Brexit effect” in which AIF managers need an EU hub post-Brexit for regulatory reasons. Such modifications are considered essential given the potential tax cost on the fund flows involved in modern cross border investments.

Conclusion

The introduction of the PPT into potentially many hundreds of worldwide treaties through the MLI gives a powerful additional tool to countries looking to restrict access by AIFs to double tax treaties. This could adversely affect investment by pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and other tax-exempt investors in AIFs and potentially penalise such investors unfairly from investing collectively, ultimately with negative impact to otherwise beneficial capital flows. In the meantime AIFs are looking to make practical changes to how they structure their investment platforms in order to protect returns for investors.

About the Authors

Andrew Quinn is Partner and Head of Tax in Maples and Calder’s Dublin office. He is an acknowledged leader in Irish and international tax and advises companies, investment funds, banks and family offices on Ireland’s international tax offerings. Andrew is a member of the Dublin office Management Committee. andrew.quinn@maplesandcalder.com

David Burke is an Of Counsel in Maples and Calder’s Dublin office. He is a highly experienced tax specialist and advises on international transactions structured in and through Ireland. David works with companies, banks and investment funds and their advisors to structure and implement capital markets, structured finance, asset finance and funds transactions. david.burke@maplesandcalder.com

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical