It seems perverse that the largest hedge fund managers continue to attract the vast bulk of net inflows, despite abundant evidence to suggest that smaller managers generate better performance. The HFR equal weighted indices continue to outperform their asset weighted indices by several per cent per year and manifold academic studies have arrived at the same conclusion. Redressing this balance was central to the vision of Trium Capital Co-Head, former investment banker, Shenan Dhanani, when he founded the firm in 2013, with backing from the family office of a legal entrepreneur, Robert Dow.

“The barriers to entry for emerging managers are very high and likely to get higher as this suits the incumbents, who behave like oligopolists. We identify talented managers, and help them to launch, using economies of scale to reduce the barriers,” says Dhanani. Most of Trium’s managers have previously worked at multi-billion dollar hedge fund managers such as CQS; GLG; Moore Capital; GAM; Man AHL; WorldQuant or firms that are now family offices such as BlueCrest. They can also enter the firm as smaller or mid-sized teams that have already set up a management company and decide that pooling resources makes sense.

The barriers to entry for emerging managers are very high. We identify talented managers, and help them to launch, using economies of scale to reduce the barriers.

Shenan Dhanani, Co-Head, Trium Capital LLP

As well as incubating new managers, Trium can accelerate more mature managers, and indeed has on-boarded one of the most venerable quantitative managers in London: Sabre Fund Management, where Winton’s David Harding cut his teeth. Sabre was founded in 1982 and has historically tied up with various fund structuring and distribution platforms for specific strategies. But in 2019 it joined forces with Trium, renaming its funds and moving its staff into Trium offices. Melissa Hill, former Sabre CEO and now Head of Quantitative Strategies at Trium, says, “Declining fees and rising costs, particularly for the data that quantitative managers need, led us to seek economies of scale. Trium have a robust quantitative infrastructure to support emerging quantitative managers.”

Seasoned convertible bond investor, Trium Credere portfolio manager, Oliver Dobbs, has chosen to partner with Trium rather than either going solo, or joining another multi-billion dollar firm of the sort at which he spent much of his career. As a family office backed alternatives firm Trium provides him with a happy medium between the potential bureaucracy of larger groups and the multi-tasking demands of smaller ones. “I previously worked for firms that had grown so large I had a hard time competing for the time and attention of operations departments,” he says. “Joining forces with Trium lets me focus on portfolio management safe in the knowledge that operations, compliance and risk management are being taken care of by the firm.”

(L-R): Shenan Dhanani, Co-Head, and Donald Pepper, Co-Head, Trium Capital LLP

Deal structures

Trium, which now has total internal and external capital of over $600m as of February 2020, provides investment capital, working capital, and operational infrastructure. There are 35 non-investment staff, including a compliance officer hired from Pelham Capital. This comes in return for formulaic fee-split or profit share with the manager. The normal intention is for this relationship to continue into perpetuity, so is different from some seeders who seek to take an equity stake which they plan to sell back to the manager or on to a third party in the future.

Seed capital comes from the family office that backs Trium, either directly or via Trium’s multi-PM incubation fund, The Trium Absolute Return fund which is currently comprised of internal capital, but may be opened up to external investors later this year. Trium also expects the portfolio managers themselves to invest in their own strategies, or “to eat their own cooking,” says Managing Director and Co-Head of Trium Capital, Donald Pepper, whose senior roles in hedge fund management have included being Managing Director of Alternatives at Old Mutual Global Investors (now Merian Global Investors), and working at prime brokers such as Goldman Sachs. Seed deals can sometimes be syndicated with other capital providers, and Trium’s eight sales and investor relations professionals assist with asset raising; day one assets for managers who progress to the fund launch stage have ranged from c $20m to above $100m. Sales are pursued from multiple angles: an extensive investor base supported by Trium’s customer relationship management system; industry and consultant databases; media, PR, events and awards; prime broker capital introduction teams and events, and other conferences and roadshows.

Multi-manager seeding fund

The Trium Absolute Return fund is a UCITS that has sleeves managed by each Trium manager, including some at the incubation stage and others who have set up funds. This structure allows for relatively efficient capital usage and low cost leverage from the prime brokers; exposures are rescaled to meet a volatility target of six per cent. The fund charges performance fees on just its net performance, meaning that managers bear some netting risk on these allocations, but not on their other capital.

Open architecture

Separately, managed by Andrew Collins out of Dublin, Trium Ireland operates a UCITS and AIF management company, “This was set up to ensure business continuity in the event of Brexit. Trium managers with UCITS funds benefit from economies of scale. Trium’s managers are also free to use other platforms e.g. as part of a seed capital deal. We are seeing strong interest from the top prime brokers to support smaller funds at inception because they are part of Trium. These funds would find it much harder to secure the top tier prime brokers and administrators as single start-up funds,” explained Pepper.

(L-R): Melissa Hill, Head of Quantitative Strategies, Dan Jelicic, CIO, Sabre Trium Strategies, Nikki Martin, Portfolio Manager, Tom Ayres, Portfolio Manager, and Joe Mares, Portfolio Manager.

Strategy criteria

Trium potentially runs the gamut of liquid hedge fund strategies, ranging from discretionary fundamental to systematic quantitative and everything in between; one team has a “quantamental” approach. The strategies include long/short equity, equity market neutral, global macro, systematic multi-alpha and convertible bond arbitrage. “Diversity of thought is sought, but the common strand running through the managers is that they are genuinely ‘alternative’ i.e. show low or no correlation to conventional asset classes,” says Pepper.

Dhanani leads the talent scouting and receives hundreds of applications and referrals each year, of which around one third are shortlisted. In 2018 he interviewed 120 managers but in 2019 he interviewed fewer, because the remit has narrowed. This is an automatic function of Trium broadening out its strategy range: they would not want to duplicate an existing strategy, and would only want to add a new manager who offered some diversification benefit versus the existing ones for the multi-manager seeding fund. Correlation analysis helps to determine if a manager is likely to be additive to the existing suite.

Trium has nine managers as of early 2020, and is unlikely to exceed 12 or 13, as they see little incremental benefit in terms of investment diversification. On average, Trium is likely to add two or three per year, partly to replace natural attrition. Of course, not all succeed: some managers incubated have not progressed to the next stage, usually due to lacklustre investment performance.

2013

Shenan Dhanani founded Trium Capital in 2013

Multiple stages of maturity

Trium can let managers develop a track record over several years before launching a fund. “Managers are Trium employees, should expect a relatively modest base salary and should have skin in the game by investing in their own strategies,” says Dhanani. Managers work with Trium at four levels of maturity. The incubation phase, lasting 6-24 months, will involve capital from the incubation fund, daily risk monitoring and broader monthly risk reviews. Launch phase requires external day one co-investors and investors willing to come in early, typically for lower fees which leads to higher total returns for their clients. This phase tends to last a few months before moving to the growth phase where assets are ramped up at more standard (higher) fees as the fund’s track record and critical mass has been established. Pepper is keen to make the point that Trium will avoid excessive asset growth that could lead to alpha decay or style drift. “The manager implements their own strategy as has been bought into by investors. Trium acts as independent risk manager and oversees that the strategy is managed to seek to deliver outcomes expected by its investors,” says Pepper. (We profile the four managers at this stage in early 2020 later on in this feature).

The fourth stage might have historically involved a spin out, as seen with the first manager, Selvan Masil of Westray Capital (who featured in The Hedge Fund Journal’s “Tomorrows Titans” report). But now Trium expects such managers to remain in-house – and might even on-board managers who have reached this stage alone or as part of other firms.

Cultural fit: collaboration and alignment

Some applicants will not get through investment due diligence while others could fail on softer criteria. “Ethical values and cultural fit are a pre-requisite,” says Dhanani. “For instance, if reference checks with former colleagues reveal that prospective managers were not collaborative this will likely lead to us concluding the process,” says Dhanani.

Culturally, Trium is collegiate as opposed to the “eat what you kill” ethos of some siloed multi-strategy platforms. Sabre Trium CIO, Dan Jelicic, envisages, “shared data and research projects with other teams at Trium”. Trium European Equity Market Neutral portfolio manager, Nikki Martin, says, “Trium openly encourages collaboration and has a pleasant office culture and environment,” and adds, “there is good operational and risk management functions, and strong sales and marketing support”. This matters because managers who join Trium are taking a medium to long term view on their careers. “In the early years, multi-strategy platforms that pass-through performance fees to individual teams may offer larger immediate AUM and more competitive remuneration. But some managers who joined Trium have turned down offers from such managers. On a medium-term view, managers who are able to set up their own fund might expect to be better off on a three or more year view and like the idea of running a stand-alone hedge fund,” says Pepper.

Trium is nurturing its managers to maximise their chances of attaining commercial success. Once managers reach the fund stage, Trium often cap their total expense ratio (TER). This is set at 0.50% on top of the management fee for two of the funds. It ensures that their performance is not handicapped by an excessive fixed cost drag, and underscores the importance of aligned interests. “We are subsidizing this from working capital and expect we may lose some money on the TER cap until managers get to critical mass,” says Pepper. (The TER cap applies to line items that the FCA defines as ancillary, such as legal and administration, but does not include trading commissions or leverage costs, which are part of gross performance). Research costs under MiFID II and data costs are also borne by Trium rather than being charged to fund investors.

Diversity of thought is sought, but the common strand running through the managers is that they are genuinely ‘alternative’ i.e. show low or no correlation to conventional asset classes.

Donald Pepper, Co-Head, Trium Capital LLP

Tailored risk constraints

Managers’ risk frameworks are tailored to their strategies rather than being centrally dictated and standardised controls. “We have had refugees from other firms, where risk limits can be much tighter, who say that they had capital withdrawn from them, even though they have not breached limits,” says Pepper. “That said, Trium’s risk managers do have a power of veto in cases where managers are ultra vires,” he clarifies. Trium has built a proprietary risk system for monitoring UCITS constraints, and uses leading vendor packages such as Eze compliance. Trium’s Investment Committee monitors all of this. Trium’s risk management team also aims to enrich managers’ processes by alerting them to factor risk exposures – and also increasingly ESG risk factors.

Diverse perspectives on ESG

Trium signed up to the UN PRI in 2015 and has retained a consultant, Kukua, to advise on the ongoing development of their ESG policies. But the plan is to leave managers latitude to apply and develop their own policies. Trium do not enforce adherence to ESG ratings agency scores, not least due to the mixed quality of data and differences of opinion between the agencies. Trium is of the opinion that ESG need not detract from returns, but also that negative screening is a rather crude way to implement ESG. The only hard and fast prohibition is direct investments into cluster munition makers.

One of the debates in ESG hedge fund investing is whether companies with low ESG scores are legitimate candidates for short books or if they should be removed from the investment universe altogether. Trium keeps an open mind about managers either owning or shorting both stronger and weaker ESG companies as a source of alpha, and indeed engaging with them on the long side to try and generate alpha from ESG improvements. For instance, power companies shifting their feedstocks from coal to gas or renewables should reduce their carbon footprint over time. This flexible framework affords Trium ESG Emissions fund portfolio manager, Joseph Mares, who previously worked at Société Générale, Moore Capital and GLG, the freedom to carve out his own distinctive approach to constructive ESG engagement.

Sabre Trium’s CIO, Jelicic has a different take on ESG. Sabre excludes tobacco in addition to weapons, but beyond that, “We use no formal ESG quant or factor screen. We think ESG would be hard to codify into a quant process.”

Trium European Equity Market Neutral has another, more nuanced, perspective. “Our quality factor has a very high correlation with ESG, mainly because the G – governance – is highly correlated. We tend to find management teams with good governance are using capital efficiently and are keen to communicate about ESG. We have a sense check to make sure that the long book overall has higher ESG scores than the short book,” says Ayres. But this is not an ESG fund. It has owned clothing retailers (such as Primark owner Associated British Foods) that are subject to some controversy around supply chains. It also currently owns a tobacco company (Swedish Match) that is generating extraordinary growth from nicotine patches, and to a lesser extent oral snuff tobacco, as well as continuing to sell flavoured cigars. This is not the first time that this team have identified growth segments within a declining industry that sometimes features on ESG exclusion lists. They also owned a mid-cap Danish brewer that saw its share price quintuple over a number of years.

Sabre Trium Equity Arbitrage and Dynamic Equity

Choosing where and how to innovate

A continuous track record since its inception date of August 2002 makes Sabre Trium’s CIO, Dan Jelicic’s Sabre Trium Equity Arbitrage strategy one of the longest running purely quantitative European equity market neutral strategies we know of. “Hardly any of our competitors at the time are still around. They often disappear,” says Jelicic, whose strategy has made money over all three-year rolling periods since inception.

Fundamental factor rotation

This is the original Sabre equity strategy (previously named Sabre Style Arbitrage), which has maintained an equity beta of near zero, but has never kept factor weights constant. The rationale for factor or style rotation was set out in a vintage piece authored by Melissa Hill, Sabre CEO, in issue number six of The Hedge Fund Journal back in 2004. Sabre were ahead of their time in introducing factor rotation at a time when the received wisdom was to maintain static factor exposures. Nobody denies that the different factor premia returns fluctuate enormously over time, but whether and to what extent these alphas and factors can be timed in a repeatable and statistically robust manner is intensely debated (viz AQR’s Cliff Asness versus Research Affiliates’ Rob Arnott). The Sabre Trium strategies have demonstrated that it is possible to time factors through multiple cycles. “We were style agnostic from the start. We always had an overlay of style rotation. This has generated an average of 25-30% of net performance,” says Jelicic. He adds that alpha from timing alphas also follows its own cycles. “Style rotation alpha does vary through time – it could be 50% of returns in some years and nothing or negative in others,” he says.

In contrast, Sabre Trium has not majored on innovation in terms of redefining factors or introducing new fundamental equity factors. Factor definitions, based partly on historical company accounting data and earnings estimates, have remained fairly consistent over time, but Sabre is keen to define the well-known ones more precisely. For instance, Jelicic points out that the low beta factor should not be conflated with the low risk factor. “The two may often be highly correlated, but Tesla is a good current example of a low beta stock that is very high risk in terms of volatility, on a five-year lookback. We have faith in the low beta anomaly, based on research such as the academic paper ‘Betting Against Beta’ – and are of the opinion that central bank quantitative easing and liquidity injections have been supportive of this factor,” he says.

Technical statistical arbitrage

This fundamental approach is complemented by a purely technical (price and volume data based) statistical arbitrage strategy, which is also designed to perform well during inflection points that can be challenging for factor investing. The stat arb sleeve explains why the strategy trades large caps and the upper ranks of mid-caps (800-1,000 stocks in the US and Europe) but avoids small-caps, which are too expensive to trade short term time frames of one day to two months. These are in fact relatively long by stat arb standards, in a space where some funds are trading intraday. “We have innovated our stat arb program in terms of new frequencies, time horizons and techniques,” says Jelicic, but the firm has not ventured into anything approaching high frequency trading. Sabre Trium’s experience of stat arb in fact predates Jelicic’s arrival at Sabre, as it launched one of Europe’s first stat arb funds in 1996.

Taking the fundamental and technical sleeves together, Sabre Trium rebalances around 40 models, and this is all systematically driven by an optimiser, in contrast to those quantitative managers who exercise discretion in their allocations amongst models. Sabre Trium’s optimiser takes account of both recent performance and the diversification benefit of models.

Tactical directional tilts

“If the core market neutral approach has seen evolutionary change with R&D, the real revolution in our strategy was introducing directionality by launching the Sabre Trium Dynamic Equity fund in 2013,” says Melissa Hill. There were two reasons. “One was a desire to capture the equity risk premium because markets go up over time,” continues Hill. “The other reason for allowing some long exposure was that history showed that since 2002 roughly 60% of the alpha has come from the long book and only 40% from the short book, and this is quite typical of other long/short and equity market neutral approaches, according to academic research,” says Jelicic. Though this was revolutionary measured against the yardstick of a strictly and purely market neutral approach, in fact the realised beta of 0.18 to 0.20 would be within the parameters that many allocators and databases (such as Morningstar) use to define market neutral.

Even this sliver of beta is not hard wired but tactically varies. “Proprietary models for adjusting beta exposure are carefully calibrated and tested based on in-house sentiment measures and some exogenous ones,” says Jelicic. “The backtest would even have gone net short twice, though it has always been net long during live performance since 2013,” he adds.

Idiosyncratic attribution

Nonetheless, over 50% of risk and performance attribution remains stock specific; around 20% is equity beta and the rest comes from the limited factor bets permitted within a tight framework of risk constraints. “Viewed through the lens of traditional performance attribution, over 50% of returns are unexplained alpha, but I can explain the returns are coming from our proprietary factors,” reveals Jelicic.

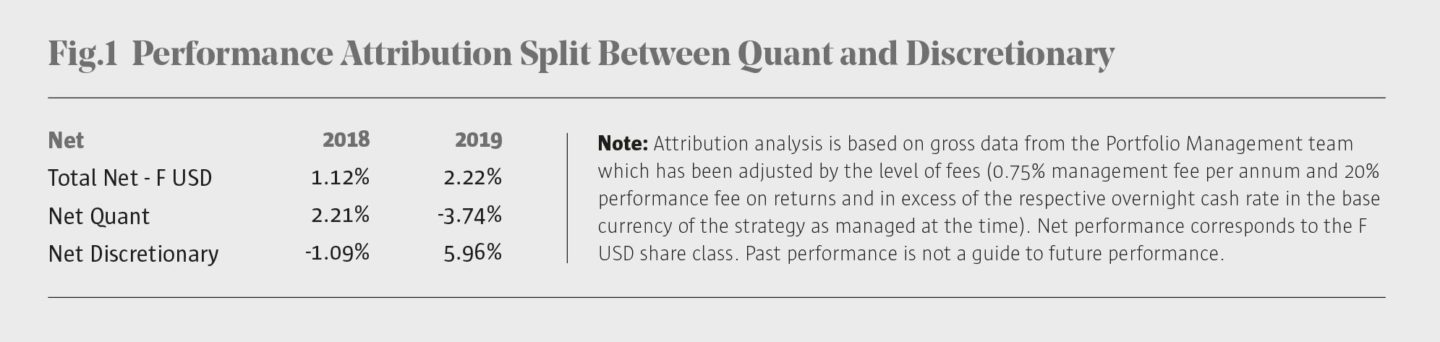

The strategy has generated a Sharpe ratio above one since inception in February 2013 and has received The Hedge Fund Journal’s UCITS Hedge performance award. The overall return profile has thus been comparable to equities but with much lower volatility. The strategy has not escaped the headwinds for quant equity market strategies in 2018, but has delivered some of the best performance in the space in 2019. Taking the two years together, net performance remains ahead of peers and indices.

Innovation in data and techniques

Sabre Trium uses proprietary data including sentiment measures, and some unstructured data, that might be dubbed as “alternative data” but is not making use of data sources that are not normally public, such as expensive credit card data sold by data vendors.

Whether Sabre Trium employs machine learning is partly a semantic question for Jelicic. “People now define machine learning however they want to. For years we have been using techniques such as cluster analysis, dendrograms, hierarchical techniques, sound robust techniques, and expectation maximisation algorithms, which are now fashionably described as machine learning or artificial intelligence. You need to know what you can and cannot use in statistics. We have started using some non-linear techniques for unstructured data, but it is hard to blend this in with what is already a very strong process.”

Currently Sabre Trium strategy assets are c $320m, and Jelicic estimates capacity of c $1-2bn for the market neutral and long/short strategies together (which implies gross assets of around $6-7bn given gross exposure of 300 to 350%). “Size is the enemy of performance and some rivals have taken in too many assets. We are always determined to put investors’ interests ahead of asset gathering,” says Pepper.

Trium European Equity Market Neutral (TEEMN) UCITS

Fundamental analysis augments quant models

Assets of $123m as of December 2019 make this the second largest Trium fund, after Sabre Trium Equity Arbitrage. It was Trium’s largest launch to date partly thanks to day one capital from a UK based wealth manager, in addition to the capital from portfolio managers, Trium Capital and Trium staff.

Portfolio managers, Tom Ayres and Nikki Martin, have worked together for 15 years and have a track record of consistent alpha over nine years: returns of 4.8%, a standard deviation of 2.8%, and a worst cumulative drawdown of just 3% at Trium, Aldersgate, Ivaldi and BlueCrest, with a slightly negative correlation to equities. The term “quantamental” can simply mean a purely quantitative process using fundamental data, but TEEMN combines quantitative models based on fundamental data with discretionary fundamental analysis. Historically, the quant models have generated a Sharpe of around one and the discretionary fundamental analysis has increased this to nearly two. Attribution has been broad based by country, sector, factor and stock, which are all subject to exposure limits. Performance drivers vary from year to year. “In 2019, quality and value stocks in the UK made a notable contribution while in other years industrial stocks could have made a big contribution,” says Martin. There is some tilting of factor weightings, without aggressively timing them, and these dynamic re-weightings have added 0.50% to 0.60% per year to returns, which is over 10% of net returns.

Dynamic rebalancing of proprietary factors

Returns in 2018 and 2019 have been below the long run average. In common with most quantitative equity market neutral approaches, the models have lost money over 2018 and 2019 taken together. One headwind has been outflows forcing competitors to liquidate billions of dollars’ worth of positions. Another, probably related force, has been the violent reversals seen in factor returns. Value has experienced resurgences but they have not lasted more than six or eight weeks before growth, quality and momentum have been re-asserted. As the bull market has progressed, the value style is no longer merely underperforming growth but now sometimes incurring absolute losses. “Value has seen an absolute de-rating while quality has seen an absolute re-rating,” says Ayres.

The pattern of returns from their quant models – making a small profit in 2018 while the HFRI Market Neutral index was down – shows that their factors are somewhat different from peers. Proprietary value, growth and quality factors, are subdivided into 17 more granular factors that tend to have a forward looking flavour. “For instance, quality is defined more in terms of improving margin trends than based on absolute historical levels of margins. Momentum also emphasises improving fundamental variables rather than historical share price momentum. And growth is seeking surprises in sales or earnings rather than their growth – which may be already in the price,” explains Ayres. The factor definitions have also been adapted over time, jettisoning metrics, such as price to book value that have performed especially poorly.

The portfolio can tilt between 15% and 45% towards individual factors, and will not short factors. Factor exposures sum up long and short books, so being short an expensive stock also counts as long exposure to the value factor. In early 2020, the manager views the quality factor as being very richly priced and value as very unloved, so the portfolio’s bias to value is towards the top end of the range. Martin sees huge valuation dispersion as some stocks have seen their valuation double or more in a few years to reach all time high relative valuations while others are trading at their cheapest ever valuations relative to the market. “It is dangerous to disregard value as investing all comes back to fundamentals,” says Martin, who also finds it hard to justify why some lossmaking companies are being rewarded for acquiring other lossmaking firms.

Factor investing returns might improve under either bullish or bearish scenarios for the wider market. “If the bull market continues it could broaden out beyond growth and technology, particularly if regulators begin to scrutinise the monopolistic qualities of tech earnings. When we see a bear market, growth and quality may be too expensive to be defensive,” says Ayres. Equally, Martin recognises that current market trends could extend further, not least because they are reinforced by a feedback loop of flows. “Outperforming funds attract more inflows and then reinvest in the quality, growth and momentum stocks,” she says. The pair will not “bet the ranch” on value, and sometimes over-ride quant value signals for various reasons.

Discretionary fundamental: augmenting and over-riding quant signals

The models are the foundation, on top of which discretionary decisions are made. The quant models rank 1,000 stocks to identify good candidates but the portfolio of 140-180 stocks, with position sizes up to 2.5% of NAV, is more concentrated than those market neutral strategies (including several others at Trium) that can trade a thousand or more stocks, partly because discretion is part of the process. The quant output can be over-ridden by discretion, which turned overall strategy returns positive in 2019. Recently there have been more over-rides than normal, for both long and short quant signals. “If stocks are optically very cheap, but there is absolutely a structural reason for this, they may be a value trap,” says Martin. A South African retail conglomerate (Steinhoff) looked good on a quant screen, but Martin, a qualified accountant and experienced private equity manager had concerns about the firm’s accounting and so did not buy the stock (while not actually shorting it). She is wary of aggressive accounting and certain accounting adjustments, which might include insufficient provisioning in some UK support services firms or capitalising excessive amounts of R&D spending.

Quant signals can also become overly pessimistic: “If sentiment and recent earnings, tax and currency considerations have been poor the quant models may be negative, but we might still hold the stock if we believe in the fundamental story. For instance, we have confidence in the management team and online strategy of a UK clothing retailer (Next).” The managers are also wary of quant overcrowding at extended levels where sectors may be near a turning point. For instance, in late 2015, growth and momentum factors were very negative towards commodities and oil stocks, which were trading at huge discounts.

Unlike many quants, the managers continue to interview corporate management, and have met most investee companies several times, partly to form a view on whether they are overconfident. Unlike some quants who are mainly desk based, Ayres spends 75% of his time on fundamental analysis including company visits. Most positions require a catalyst for investing, which could include a new CEO, an accretive acquisition, or offshoring the cost base for longs.

“We balance a rules-based strategy, with a discretionary approach to optimise the quant process,” says Martin. Behavioural finance biases inform both the quantitative and the fundamental processes. But other techniques used are more grounded in traditional statistics, and do not employ artificial intelligence, machine learning or natural language processing. “We are not getting into an arms race of quant development, optimisation and TCA models,” says Ayres.

The investment universe is reasonably liquid mid and large caps with market caps of at least $750m that they would define as mid caps (although a handful of positions might be classified as small cap depending on thresholds). Strategy capacity is estimated at around $1bn.

Trium Credere

Catalyst driven convertibles and hybrid alpha

“I lived and breathed game theory in the 1980s when nobody else thought about it,” says Credere Capital LLP CIO, Oliver Dobbs, who studied Zoology (now called Biological Sciences) under Richard Dawkins at Oxford University, where Dobbs was also immersed in statistics and computer science.

Game theory can inform trading convertibles by providing a framework for predicting whether, when and how a company might choose to refinance debt prior to maturity, for instance. Dobbs judges that, “pattern recognition and other systematic coding techniques are increasingly important drivers for the equity markets”. But he contends that computers cannot yet cope with the complexities of more exotic and idiosyncratic credit and hybrid instruments and finds artificial intelligence and quant driven flows are more likely to throw up precisely the anomalies that he exploits, rather than threatening the strategy. His early career employers, investment banks, are not putting up much fight either as their retreat from proprietary trading has left fewer competitors chasing these opportunities.

Complexity and catalysts

The Credere strategy trades mainly hybrid credit in the US and Europe, and trades around the complexity of prospectuses, which can contain clauses on convertibility, cross-default scenarios or ratchet uplifts upon takeovers. Dobbs analyses these features from multiple angles, including a significant minority of trades that revolve around accounting and tax complexities. He hedges out the equity and credit risks to negligible levels, to isolate mis-pricings and create potential profits from special situations, such as: news events; new issuance; buy backs; tender offers; flushes; restructurings or regulatory changes. He also trades a repertoire of relative value trades that are sometimes akin to more traditional convertible arbitrage trades such as gamma trades feeding off volatility; synthetic put options constructed at low, zero or even negative cost; and busted convertibles trading close to their bond floors. He can also take a view on relative value within the capital structure. And Dobbs relishes trading more complex instruments, such as “mandatories”, that fall between equity and credit stools and may therefore deter other market participants.

The philosophy is based far more on anticipating catalysts than are some mean reversion oriented relative value approaches. Nearly all positions require a foreseeable catalyst, though this is more likely to be a corporate action such as a rights issue, new issue, reorganisation, earnings surprise, bond maturity or call, than a corporate event such as a takeover. Changes in credit ratings can also provide a fillip for some trades, such as one that could make a few bond points if a company gets upgraded due to being reclassified into a different industrial sector, but which is not expected to lose money if this does not happen.

Portfolio construction does not engage in trades found in credit strategies but seeks to take advantage of long implied volatility exposure due partly to the embedded options in convertibles. It starts from the bottom up and all of around 30 trades are intended to be independent profit centres. They can be put into various buckets but the choice of trades is completely opportunistic so some sleeves – such as Japanese warrants in early 2020 – may not be populated.

Global purview

Having thrived on the cut and thrust of bank trading floors, Dobbs also has the market savvy to appreciate the human side of trading. Over a 35-year career Dobbs has lived and worked in Tokyo and New York, and he argues that, “you cannot appreciate the cultural differences of Japan and trade that market unless you have lived there. And as for our US cousins, you just don’t get it without having worked there.” He runs a global portfolio to benefit from the low correlations amongst the major regions but anyway finds plenty of idiosyncratic volatility in his universe. Individual equities and credits are demonstrating a decent amount of dispersion, despite the subdued broad index volatility that many hedge fund managers bemoan.

This diverse repertoire of trade types has helped Credere to grind out steady and consistent returns in the high single digits since inception in September 2017. The strategy is lowly correlated: returns in the fourth quarter of 2018 of around 1.8% were very close to the annualised average of 7.2% since Credere started. Profits come mainly from trading; positive carry around one per cent only just about defrays the management fee. There have only been four losing months since inception. Tight risk controls aim to limit losses per trade to 0.5% and Dobbs has exited certain trades, such as an oil company (Tullow Oil) that issued a profit warning, at much smaller losses. He also sold a bond in a South African company (Steinhoff) before accounting fraud emerged.

This track record continues Dobbs’ 30 years of experience in the convertible bond markets. Dobbs has been a trader, working for CQS founder Michael Hintze at Goldman Sachs, and later at CQS, and spent a decade managing money for Tribeca. He also has war stories from winding down the LTCM fund during 1998. Dobbs has a portable ten-year track record spanning several firms.

Liquidity and scalability

Dobbs has seen worse convertible bond market liquidity at the start of his career in the late 1980s, and better liquidity in the early 2000s, before the GFC; though the picture is mixed: he cites research from Barclays showing an improvement in US convertible market liquidity in 2019. Currently, independent risk managers estimate that over 90% of Trium Credere’s book could be liquidated within a day, and capacity for the strategy is around $1bn of net assets, which implies $3-4bn of gross assets given leverage of up to three or four times, which is less than some other firms trading this strategy use. As assets – which reached $56m as of February 2020 – grow, some less scalable trades will have less impact on the P&L but new opportunity sets will open up. Dobbs expects to get more competitive financing and security borrow rates, and also envisages revisiting the sorts of capital market trades that he did in former jobs where he managed up to $2bn. “We would get sounded out more often on issuance pricing,” he says. In the meantime, buoyant issuance of convertibles is expanding the investment universe and Dobbs is garnering allocations to new issues. Dobbs is confident alpha will not be diluted at higher AUM levels, saying that, “93% of our current portfolio could be scaled up if AUM were $1 billion”.

You cannot appreciate the cultural differences of Japan and trade that market unless you have lived there. And as for our US cousins, you just don’t get it without having worked there.

Oliver Dobbs, Chief Investment Officer, Credere Capital LLP

Trium ESG Emissions Impact UCITS

Can the biggest emitters attain redemption?

The Trium ESG Emissions Impact UCITS fund’s return target of cash plus six to eight per cent is not unusual nor are its neutral exposures to equity markets, sectors and commodities. But its return pattern is likely to prove very differentiated from many thematic ESG funds because its holdings are not likely to have any overlap with the most obvious and popular ESG names, in some increasingly fashionable areas of the market – such as wind farm operators – that may now be quite richly valued on 12-15 times EBITDA.

Some ESG investors eliminate the negative, through exclusion, while others accentuate the positive, through impact investing. But a growing proportion prefer to emphasise engaging with companies to improve their ESG profile, with the main intention being to extract alpha from valuation expansion for longs. Trium ESG Emissions Impact portfolio manager, Joe Mares, fits into the latter group and is distinguished by focusing on the biggest emitters, selecting from a universe of 300 mid and large cap stocks in the energy, resources, materials, utilities, chemicals, transport and industrials sectors, which together make up roughly one third of the MSCI Europe, but account, according to Mares’ estimates, for 90% of carbon emissions. “We are targeting those that can improve their carbon footprint through organic operational improvements to their existing activity or sometimes changes in their business model (and not through unrelated offsetting activity such as reforestation or buying carbon credits). This narrows the shortlist down to perhaps 30 or 40 companies with scope to improve in an environmentally efficient way,” he says.

Mares is throwing down the gauntlet by asking: “Do you want a clean portfolio or a clean planet?” Alternative energy and renewables companies may have little or no scope to improve their behaviour. It is easy enough to avoid investing in polluters, but this does nothing to change their behaviour.

Proactive, constructive and private engagement

Mares, who has run money for Société Générale and worked on the buy side for Greg Coffey at GLG and Moore Capital, identifies firms that have the potential to see a valuation rerating, and often also earnings growth, from improving their ESG profile. A classic example could be Neste of Finland, which has successfully transitioned to biofuels. Investors were initially sceptical, but the stock has been a ten-bagger over a ten-year period.

“We tend to avoid the mega cap stocks as we have little potential to add value to their extensive policies and presentations,” he adds. Mares focuses on companies that may have little or no ESG communication, and no score (or possibly a poor one) from ESG ratings agencies.

His engagement prioritises the E in ESG and within that focuses on emissions. Mares does not deny the importance of water and waste issues but he is focused on the six Kyoto protocol gases, which have the advantage that C02 equivalent data is relatively easy to find and analyse.

Disclosure is the first step, and is still missing from some firms. He contends that “there is no good excuse for companies not reporting and forecasting their carbon emissions in a full manner, considering Scope 1, 2 and 3 levels of emissions, which can be forecast with a much smaller margin of error than the future earnings of cyclical companies. If companies are not publishing this information, we will estimate it from first principles rather than rely on opaque third party data – and will openly share the calculation methodology with the companies concerned and seek their feedback.”

Actions to reduce emissions are the next step. Rather than asking firms to fill out boilerplate and sometimes onerous standardised questionnaires, Mares is proactively proposing solutions specific to their activities. As a former sell side equity analyst, Mares has some flair for presenting ideas that are getting a positive reception. He gets invited to board meetings, but is not an activist and does not seek to install his own directors onto boards or comment on S and G matters such as remuneration. Mares is not seeking any fame as he fears this could make it more difficult to interact with other companies. Even so, the fund’s Impact Report lets investors know which companies it has engaged with and monitors what measurable improvements have been achieved.

ESG ratings reshuffle ahead?

Where target companies have an ESG rating, Mares is not reliant on the disparate opinions expressed by external ESG ratings agencies, but he does expect a shakeup in ESG scores could create some share price volatility. The subjectivity of ESG ratings is now widely understood but even where a high degree of consensus currently exists, investors should be braced for an upending of current scores. Mares envisages a confluence of disruptive factors will reshuffle corporate ESG rankings: TFCD (the Taskforce for Climate Disclosure), the EU’s new green taxonomy increasing the granularity of fund classifications, and growing disclosure and analysis of Scope 3 emissions.

Scope 3 data adds to the Scope 1 data of companies’ immediate carbon footprint, by calculating the impact to the environment generated by their supply chain and customers. Currently, the most widely followed standard – the GHG protocol – requires reporting of Scope 1 and 2 data (the emissions effect of energy used by its suppliers). When this changes, and Scope 3 data is taken into account investors will have to reassess their opinions of some companies where they begin to recognise that Scope 3 data could prove to be more important than the Scope 1 and 2 data. An example could be an iron ore producer (Ferrexpo) currently reporting high Scope 1 and 2 emissions due to an energy intensive production process, but which has lower Scope 3 emissions because its output – a particular type of pellet – consumes less energy during the ultimate end use of steelmaking. Similarly, a glass maker might be a big carbon emitter, viewed in isolation, but its double-glazed windows might allow buildings – the largest source of emissions – to economise on fuel. In both cases, the “net net” carbon footprint could be reappraised as being relatively good, even though Scope 1 and 2 data are still high in absolute and/or sector relative terms.

Another key weakness with standardised ESG ratings is that they are backward rather than forward looking. An energy or power company transitioning from oil or coal to natural gas or renewable power generation should get some credit for improvements underway. This will not be apparent in e.g. latest annual reports that cover prior years.

The irony here is that ESG is all about the ecosystem, yet the prevailing analytics paradigm has so far placed more emphasis on supply chains than on end uses. Mares sees this as about to change and transform the whole economic system, not only individual companies’ behaviour. “Longs include high emitters who are improving, while shorts could include some companies perceived to be low emitters that will eventually be revealed to be part of the problem. Companies who are unwilling to engage with us are more likely to become short book candidates,” he says.

The paradigm is thus radically different from a standard ESG approach. It is forward not backward looking; it looks at the whole ecosystem not only individual companies; it is transparent, and aims to effect change through engagement and influence rather than by raising companies’ cost of capital.

Valuation enters the equation in terms of the timing of buys and sells. “We will not necessarily buy a stock on the day they announce a target for carbon neutrality,” he says.

Exclusion lists

In common with other ESG funds, Mares does have a much longer exclusion list than the minimum of cluster munitions set by Trium: rainforest logging; thermal coal mining; tobacco and alcohol; armaments; gambling and pornography and animal testing are excluded. This was specified at the behest of a Scandinavian seed investor; many of the restrictions are not actually germane to the sectors he invests in. Other seed investors included a German institution, and as usual Mares himself and Trium. The strategy ran $22m at year end 2019.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical