Where Next For Monetary Policy?

The unveiling of tools of unlimited power

ERIC LONERGAN, PORTFOLIO MANAGER, EPISODE MACRO FUND, M&G INVESTMENTS

Originally published in the October 2016 issue

Recent shifts in policy direction by global central banks may prove to be profound. Since the financial crisis, most major central banks have responded to weak growth with ever lower rates or further bond buying. Today, a consensus may be emerging that these are the policies of the past. Not only this, but both the Bank of Japan and the ECB appear to be conceding that they are in fact self-destructive.

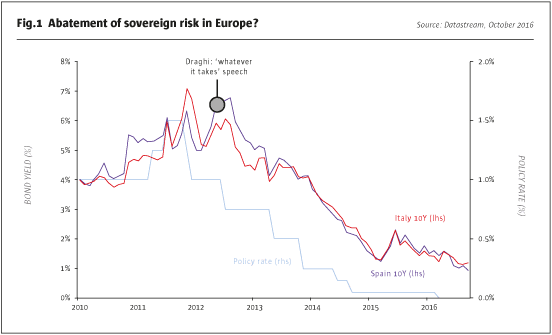

To some extent ultra-easy monetary policy has been successful in averting the worst possible outcomes from the financial crisis. In the ECB’s case bond-buying has achieved its primary objective: consigning sovereign contagion to history. Its secondary objective, strengthening the fiscal positions of European sovereigns and underpinning their accounting solvency, has also been achieved.

If ever proof was needed that Europe’s sovereign panic was induced by Trichet’s ECB rejecting QE in 2009, Mario Draghi provided us with the counterfactual. When the central bank with its printing press stands behind the government there is no credit risk, when it leaves them standing alone they are subject to runs. Such is the difference between money and debt.

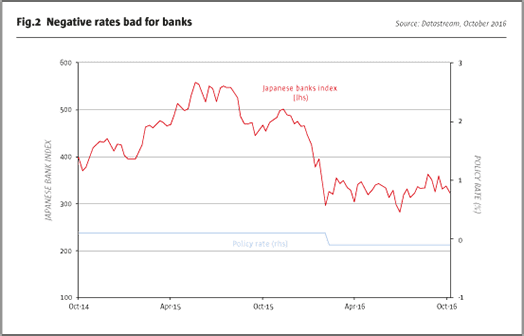

However, it has also been increasingly clear for several years that bond-buying QE and ever lower interest rates run the risk of having counter-productive effects. This is most evident in two areas; i) in the impact on consumer spending, and ii) in threatening financial stability and the banking sector.

In the case of consumer spending, the empirical and theoretical basis of lower official interest rates having a stimulative effect is weak at the best of times. But in Europe and Japan, where high GDP per capita and relatively even distributions of income prevail, angst about the future – rising health care costs, and shrinking labour forces – mean that lower rates may actually reduce spending. For those who need a fixed amount at some time in the future, lower rates simply mean that more saving is needed today.

Moreover, while it is true that more government debt (and inflation) can be a solution to a private sector debt problem, it cannot be the case that adding ever more debt is the way out for an already over-leveraged private sector. There are good reasons why credit growth has been anaemic despite the collapse in its cost. Austerity tripped on this basic fallacy.

As for banks, little more needs to be said on how negative rates pressure profits. The market reaction to negative interest rates illustrates this clearly.

Central banks are now aware that traditional tools are failing, but until now have been limited by narrow interpretations of what monetary policy entails and the nature of their own mandates. However there are increasing signs of innovation that could offer a lifeline to global economies.

So what next for monetary policy?

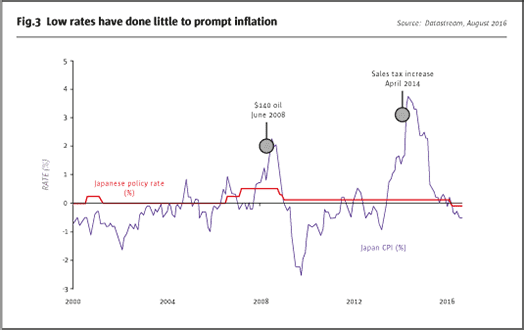

Governor Kuroda at the Bank of Japan deserves a great deal of credit for being prepared to innovate quietly. Since 2000, low policy rates and periodic bond buying have done little to shift inflation, with CPI only breaching 2% in the oil spike in 2007/8, and an increase in sales tax in 2014. However, Kuroda understands that inflation is the central bank’s responsibility, and temporary failure is no grounds for jumping ship. He is testing contemporary macro to the limit: and has committed to print money until Japanese CPI rises above its previous 2% target.

I am inclined to believe him. I don’t think many people outside a semi-religious core of modern theoretical fantasists really believe that central banks can, armed with determination alone, simply raise ‘inflation expectations’ at will, when all the evidence suggests abject failure to achieve more modest objectives. Nonetheless, the clever economists at the BoJ and ECB have been innovating busily. They have already moved far away from anything you will find in a monetary textbook.

Consider two wonderful innovations: tiered reserves and TLTROs. Part of their brilliance resides in obfuscation. Economics struggles to define ‘money’, let alone the difference between fiscal and monetary policy. It appears an inevitable feature of modern democracy that central banking must operate behind a veil of ignorance – analogous perhaps to the machinations of the secret service. In this instance, the barrier is cognitive effort.

The inventors of tiered reserves and TLTRO each deserve a Nobel Prize. What both have in common is in decoupling monetary stimulus from market interest rates.

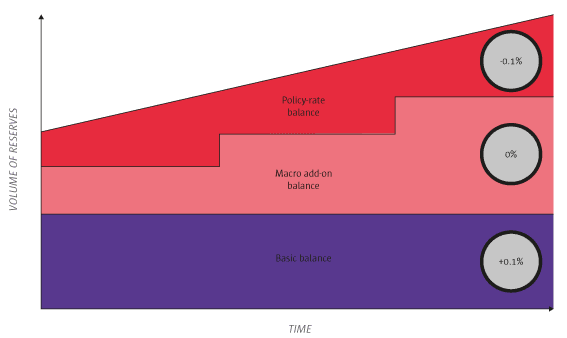

Tiered reserves

Tiered reserves make it explicit that the monetary base and T-bills, while sometime close substitutes, are in fact qualitatively different. And not just for Greece. Bills are issued into a market at a price – an interest rate. The ‘interest’ paid on reserves or IOR, is an interest rate only in name – it should correctly be named a payment (or deduction) to the holders of reserves. Central banks can set market interest rates by setting an interest rate on a fraction of ‘excess’ reserves. If they want to, they can remunerate the balance at a premium, or discount.

In future, it is conceivable that required reserves could be shrunk using negative ‘interest rates’ and excess reserves paid a premium. Some theoretical economists like to dismiss all this as fiscal policy – via the banking sector. But this is disingenuous. This is very clearly monetary policy – just not what we are familiar with. The institution is the central bank, and money is being created and destroyed. That’s about the clearest definition of monetary policy you will find.

Making elevated transfers on tiered reserves in excess of money market rates is a Friedmanite dream. Monetary policy is never out of ammunition. There is the small matter of who receives this bonanza – but requiring banks to pass it on to the corporate or household sector is an obvious next step.

Targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs)

The TLTRO has similarly broken new ground. Previously, Bagehot’s dictum was sacrosanct – central banks only ever lent to the bank sector at ‘punitive’ rates, or at least at a premium to what they paid on reserves. This was only ever convention. It has died. Since the ECB announced this year that the TLTRO would be extended to banks at the same rate as reserves were being remunerated, a whole new avenue for monetary policy has opened up.

The ECB has made explicit that there are in fact three axes along which monetary policy can be eased: duration, credit risk, and price. The TLTRO programme seems far more radical than QE, because there is literally no limit along any of these axes. So far, TLTROs have been extended for five years, at negative interest rates (subject to certain restrictions), and in the form of collateralised loans.

But there is nothing stopping the ECB from making the TLTRO programme its principal policy tool. The next step is to decouple the interest rate on TLTROs from the interest rate the ECB pays on reserves. And before anyone panics that this exposes the ECB to losses and unwarranted risks, that barrier has already been hurdled – the risk is no different to buying long-dated bonds at very low or negative rates.

Many commentators, including the Bank of England’s Ben Broadbent, seem to believe that engaging in policies with a negative net interest income to the central bank are for some reason taboo. This is a spurious form of mental accounting. QE programmes, although currently net income positive, expose central banks to the prospect of huge future net income losses (unless they use tiered reserves) – a point Chris Sims has correctly made. Furthermore, how can it make sense that central bank operations must make the treasury a profit, and never a loss? That is an entirely arbitrary asymmetry.

The Bank of Japan and Bank of England also have TLTRO programmes, with different nomenclature. A logical next step is for the duration and pricing of these directed lending programmes to be extended aggressively. There will be shrill voices crying ‘subsidies’! This too is mental accounting – what is the ‘wealth effect’ of QE if not a ‘subsidy’ to the owners of financial assets? On this logic, negative interest rates are a bailout of irresponsible borrowers. Every change in interest rates has distributional consequences, whether we like it or not.

Directed lending via the banks to the private sector provides central banks with a new bazooka. If Kuroda wants, he can deliver his new target – and Japanese real GDP may be 10% higher, if he does.

Other options

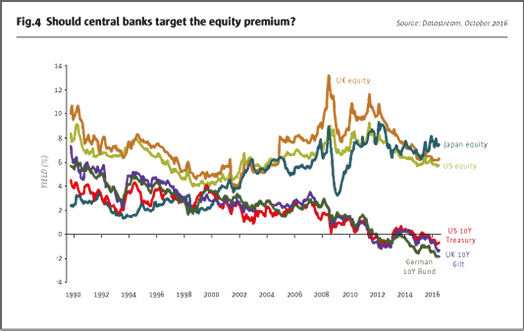

The BoJ has also innovated in targeting the equity risk premium directly. Other central banks’ focus on purchasing government and corporate bonds epitomises the very ‘risk aversion’ they are trying to combat and lacks intellectual rigour.

The great irony is that they are far more likely to make huge balance sheet losses on their bond portfollios, and BoJ officials will be high-fiving over their equity gains. The implied equity risk premium in Europe, Japan and the UK is currently enormous.

I do worry that buying what is currently a cheap asset on the scale that government bonds have been bought might rapidly create an equity bubble, but it is a far more logical way to raise investment spending than targeting interest rates on supposedly ‘safe’ assets, damaging the pensions, insurance and banking industry in the process.

Conclusion

The abandonment of ever lower bond yields by the Bank of Japan, and its attempts to raise demand by new means should be welcomed. So too should the rumours that the ECB is abandoning further QE. This is a recognition that these policies, once relevant, are now counterproductive. Our economies do not need lower government bond yields, or lower official overnight interest rates – that is surely obvious. Fortunately, the BoJ and ECB have also revealed new tools of unlimited monetary power. The next step will be a measure of their courage to use them.

THE NEW POLICIES DEFINED

Tiered Reserves

In February 2016 the Bank of Japan introduced a tiered reserve system, which mirrors the system in place in Sweden, Switzerland and Denmark.

Under this system the Central Bank seeks to mitigate the adverse impact of negative rates upon private banks’ balance sheets by ensuring that negative rates only apply to a certain portion, or ‘tier,’ of that bank’s reserves. In Japan, a large amount of pre-existing reserves continue to earn a positive rate, a smaller amount set by the BoJ will earn zero, while negative rates will only apply to new reserves created at the margin. This is intended to influence transaction prices but not bank profitability.

The aim is to ensure that negative rates incentivise banks to lend out of the new reserves created through QE but without harming profitability on the business as a whole.

Targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs)

TLTROs are simply a means of providing credit to financial institutions. Importantly however, the amount that can be borrowed and the attractiveness of the terms is conditional on a bank’s loans to households and corporates. The more a bank lends the more favourable the terms and the more that can be borrowed.

Like tiered reserves, and the Term Funding Scheme in the UK, TLTRO is a clear effort to ensure that the effects of quantitative easing are felt in the real economy and not just in bank balance sheets and asset prices.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical