After having made the case for staying the course in Japan earlier this year1, we now want to examine how to extract sustained and consistent alpha from this market, the benefits that allocating to different hedge fund styles may bring, and whether the market lends itself, perhaps more so than others, to a portfolio of managers investment approach.

To address these questions, it is helpful to review performance both more recently and over longer periods of time. 2020 has certainly been an informative year, with a plethora of data for investors and analysts to digest. No end is currently in sight to the market impact of the COVID pandemic, the long-term effects of ongoing and massive global monetary stimulus remain unknown, and the change in US government will only play out in markets over time. Despite all this uncertainty (or perhaps, because of it), 2020 has also been a very good year for certain Japanese hedge funds. Market neutral, trading oriented, multi-strategy, and some fundamental equity/long short managers in particular have been able to generate significant alpha when compared to long only indices.

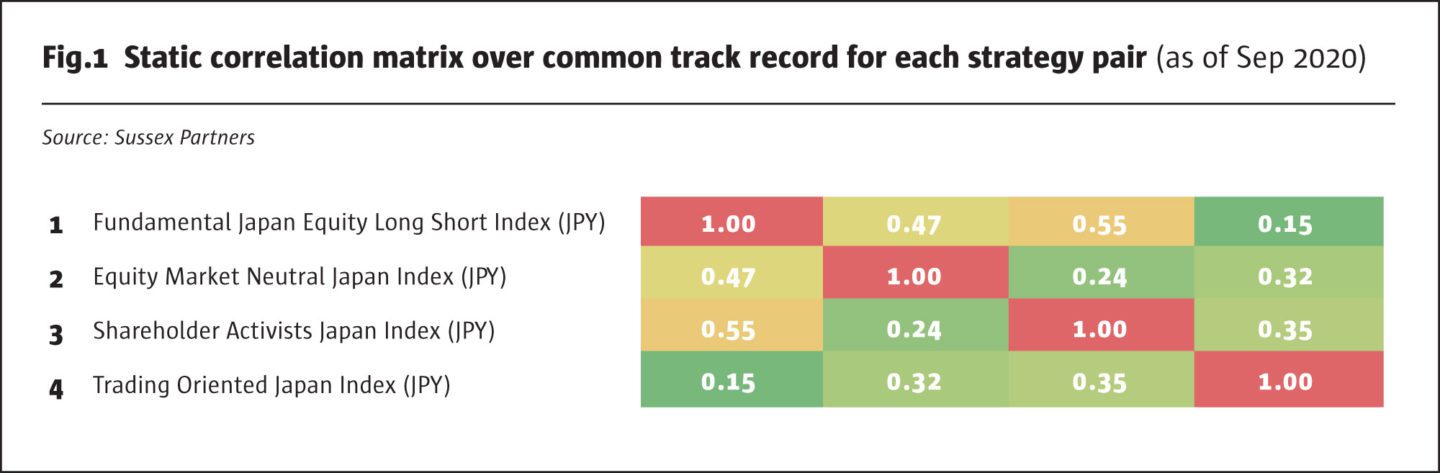

Japanese managers, even if they follow the same broad strategy tend to be quite decorrelated from one another.

Patrick Ghali, Managing Partner, Co-Founder, Sussex Partners

As is often the case though with data relating to Japanese hedge funds, purely looking at hedge fund indices does not tell the full story. The number of managers included in these indices tends to be limited, and often very different managers end up being grouped together under one heading. This means that these indices can easily be misinterpreted and provide an erroneous picture of actual performance, or the alpha available to investors. To gain a true understanding one needs to look at manager data at a much more granular level. The fact that the industry is very small also makes it a lot more difficult to create proper indices. The number of samples/funds/managers included in each data set can be very limited, a problem that only gets exacerbated when it comes to sub-indices, where one single manager can potentially significantly influence/skew that index’s performance. For example, as of the end of September of this year, the Eurekahedge Japan long short equities hedge fund index was down -5.13%, and our internally constructed Fundamental Japan Equity long short index was down -5.19%. Though this was still better than the TOPIX index, which was down -5.57%, that performance difference is not very significant and thus not overly compelling. However, by taking a closer look at the constituents of these indices we can see that there is significant dispersion of returns, and so the headline numbers do not tell the full story.

During that period, the top performing fund in our custom index returned more than +26% while the worst performer lost more than -37% and a third of the managers posted positive returns. These numbers demonstrate that these managers, though considered to be part of the same strategy, are clearly not following the same approach. Further analysis of returns reveals that, Japanese managers, even if they follow the same broad strategy tend to be quite decorrelated from one another.

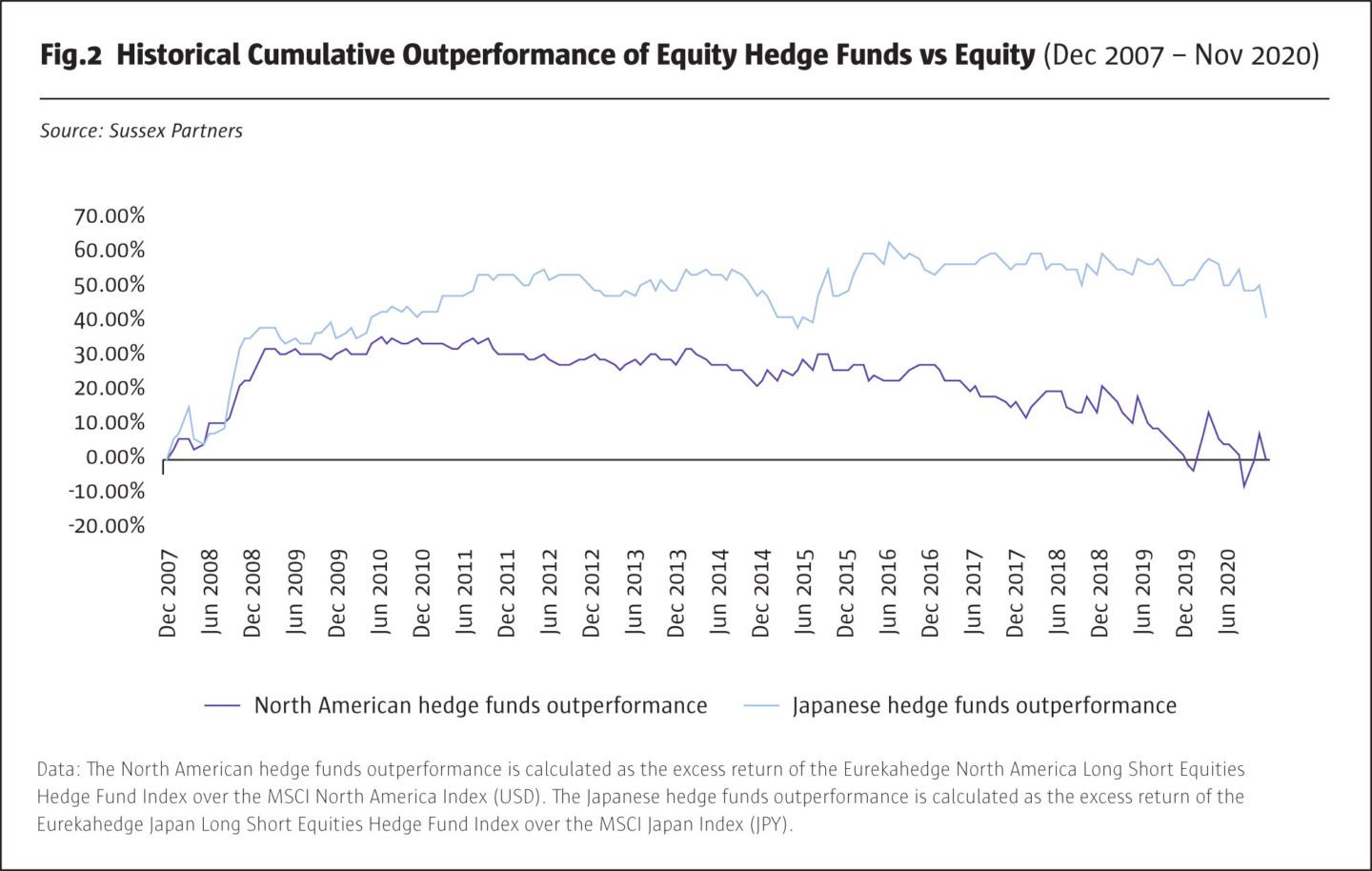

This makes intuitive sense given the large universe of stock, low prevalence of available research, and limited pool of hedge fund capital compared to other developed markets. A 2018 research paper by the Bank of Japan, which looked at data from the “Annual Survey of Corporate Behavior”2 backs this up, and came to the conclusion that due to the lack of analyst coverage, a real information advantage exists in Japan for those able to conduct primary research. This is not something one would expect based on the idea that markets generally should be efficient. The report goes on to state: “These findings suggest that the reason for the information asymmetry between firms and the market is that certain firms are insufficiently covered by analysts and that the survey responses reveal information held by firms that is not incorporated in stock prices”. To put this into further context, Japan has over 3700 listed companies, of which less than 50% have any research coverage, and, by our estimation only about 100-120 hedge fund managers competing in this space which account for approx. 0.25% of the total market cap of the Japanese stock market. Though the US is estimated to have 20% more listed companies than Japan, it also has much broader analyst coverage and approx. 30 times the number of hedge funds, all competing for alpha, and all contributing to making the market more efficient. Comparing the cumulative outperformance of US and Japanese hedge funds versus their respective MSCI benchmarks illustrates this point nicely, as it shows that US managers struggle to add value over time, while Japanese managers add significant value.

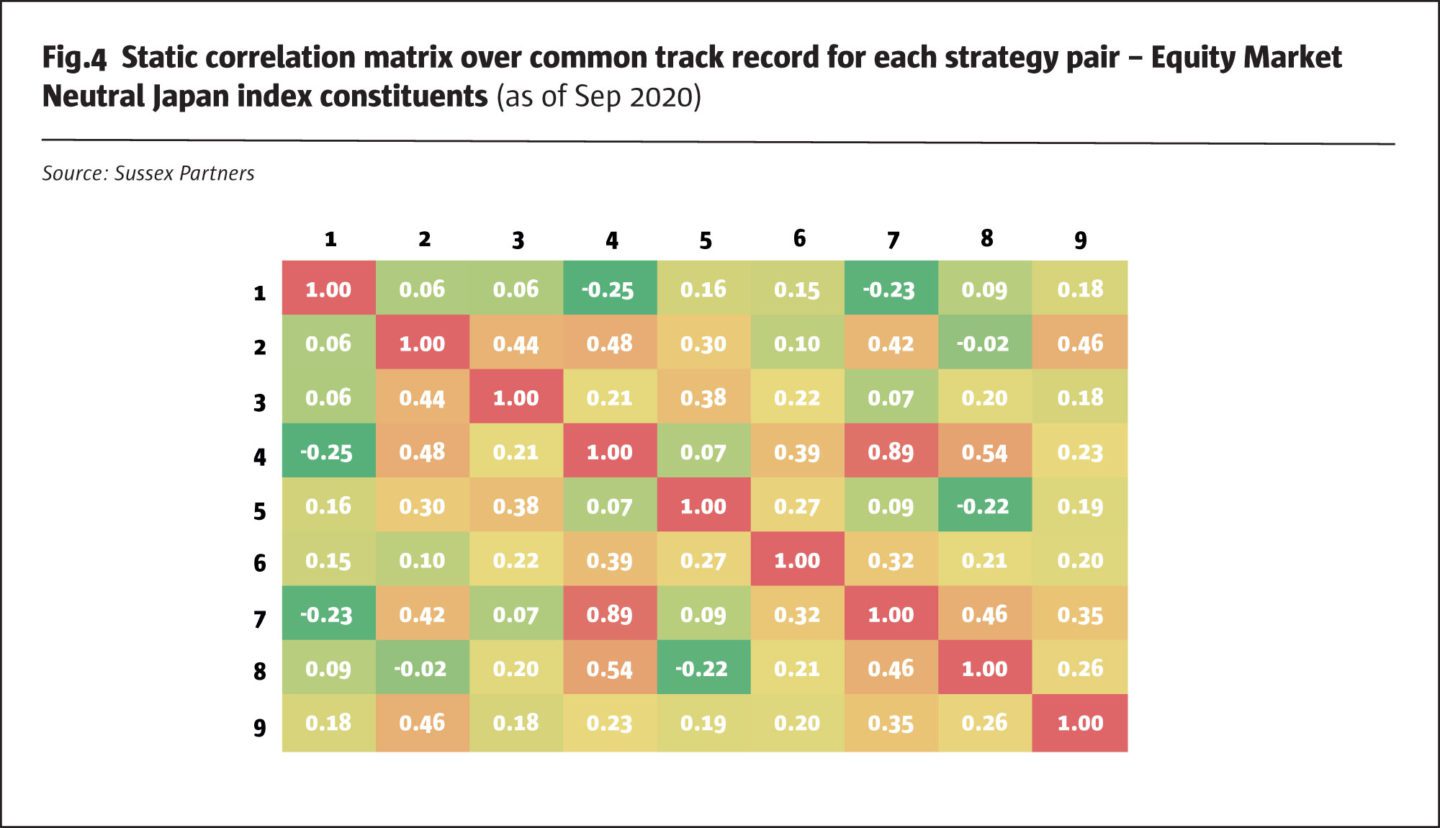

Taking a bottom-up approach as a starting point shows that managers within the same broad strategy will not only trade very different positions but will often also have a very different approach to portfolio construction. Though it isn’t unusual to see managers with over 100 positions in their portfolios, a somewhat unique feature of Japanese hedge funds, almost a quarter have less than or equal to 20 positions according to our most recent annual survey of Japanese hedge fund managers, conducted in November. But it isn’t just the amount of positions held that differ significantly from fund to fund (with concentrated portfolios being somewhat unique, and with clear implications on risk management and more prevalence among engagement/activist and event-oriented managers), but also the focus on specific market cap segments, holding periods for longs and shorts, net exposures or application of shareholder engagement methods varies widely among managers. Although 68% of Japanese managers consider themselves as having a fundamental approach to investing, according to our survey responses, this alone does not tell investors much in the absence of a deeper understanding of how this gets expressed in a broader investment context and affects other aspects such as holding periods. It is also important to understand what these fundamentals are measured against (e.g. quarterly results) and how often they get revisited. By looking at correlations amongst different managers within the same strategy it becomes clear that managers implement their strategies in quite different ways.

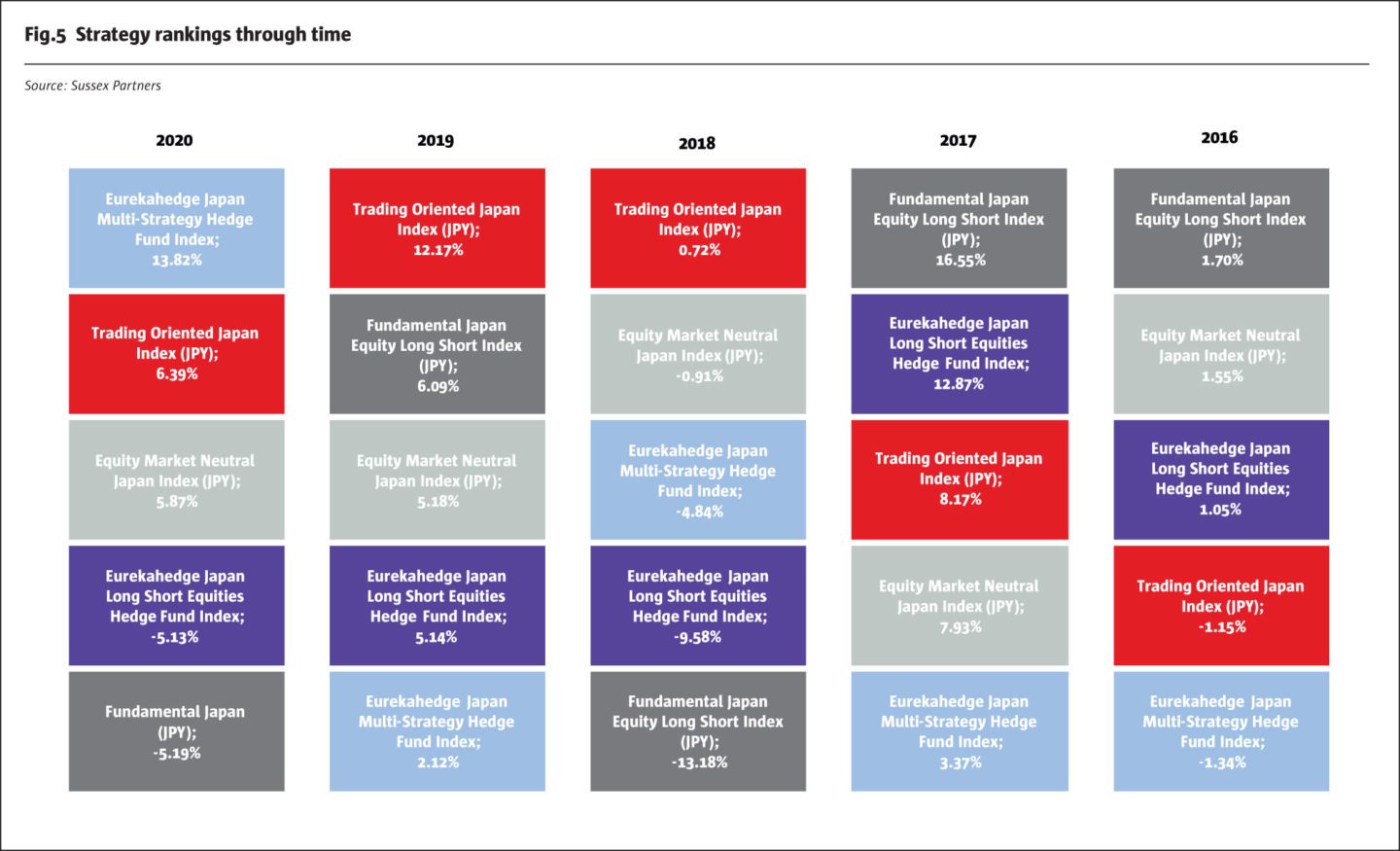

Though manager selection is clearly important, strategy selection is also key if investors want to extract long term alpha from Japan, as dispersion at the strategy level is no less significant. While the aforementioned long/short indices were down -5.13% and -5.19% respectively, our internal Equity Market Neutral Japan Index was up +5.87% over the same time period, trading oriented managers in our own index returned +6.39%, and multi-strategy managers had the highest year to date returns with +13.82% according to the Eurekahedge Japan Multi-strategy Hedge Fund index. Therefore, picking the right manager in the wrong strategy can still lead to a less than optimal outcome (refer to Fig.5).

Even more importantly though, is understanding how these different strategies perform during different market regimes. While Multi-strategy managers certainly are shining so far in 2020, investors would have been better off investing in fundamental growth oriented long/short managers in 2019 as these would have returned +10.19% versus only +2.12% for multi-strategy hedge funds (which was one of the lowest performing sub-strategies last year, and for which, incidentally, 2020 has been the best year in 5, and the only one with double digit returns). Certain strategies clearly do better in certain environments. Fundamentally driven long/short strategies, as well as value-oriented strategies, for example have suffered over the past few years as ample central bank liquidity flows, outright market intervention and direct equity purchases have led to market distortions. Shorts in particular suffered, as companies with lackluster fundamentals have been pushed up along with other parts of the market. Managers focused on fundamentals or those with a value bias found it therefore especially challenging to extract meaningful short alpha, and to really protect their portfolios in an efficient manner, with many of them recording some of their worst losses in over a decade. The perceived gap between the intrinsic value of these companies versus their market prices kept increasing over the past one to two years but has finally seen some normalization post March with fundamentals in Japan coming back to the fore in light of the pandemic. This in turn has led to many of these managers posting some of the best returns this year. Market neutral managers have also struggled to generate more than lack luster returns over the past few years, as many have been hesitant to increase their gross exposures to meaningful levels but are also having a very strong year this year. There are of course also strategies which are evergreen in nature such as trading oriented managers. These have generally been able to provide investors with consistent, albeit sometimes lower returns, irrespective of market regime. Capacity with such managers tends to be scarce and quite hard to find, and the choice of managers tends to be more limited. Understanding the broad drivers of performance for different sub-strategies therefore is important, though timing these perfectly very challenging. Therefore, a deep and thorough understanding of each manager, style, and overall market regime, is essential and allows allocators to take advantage of the manifest differences among managers to construct more robust portfolios and to extract different alpha sources at different points in time. This understanding is garnered by conducting quantitative analysis including of mangers’ returns as well as detailed qualitative work to get as much understanding of the manger differentiators as possible.

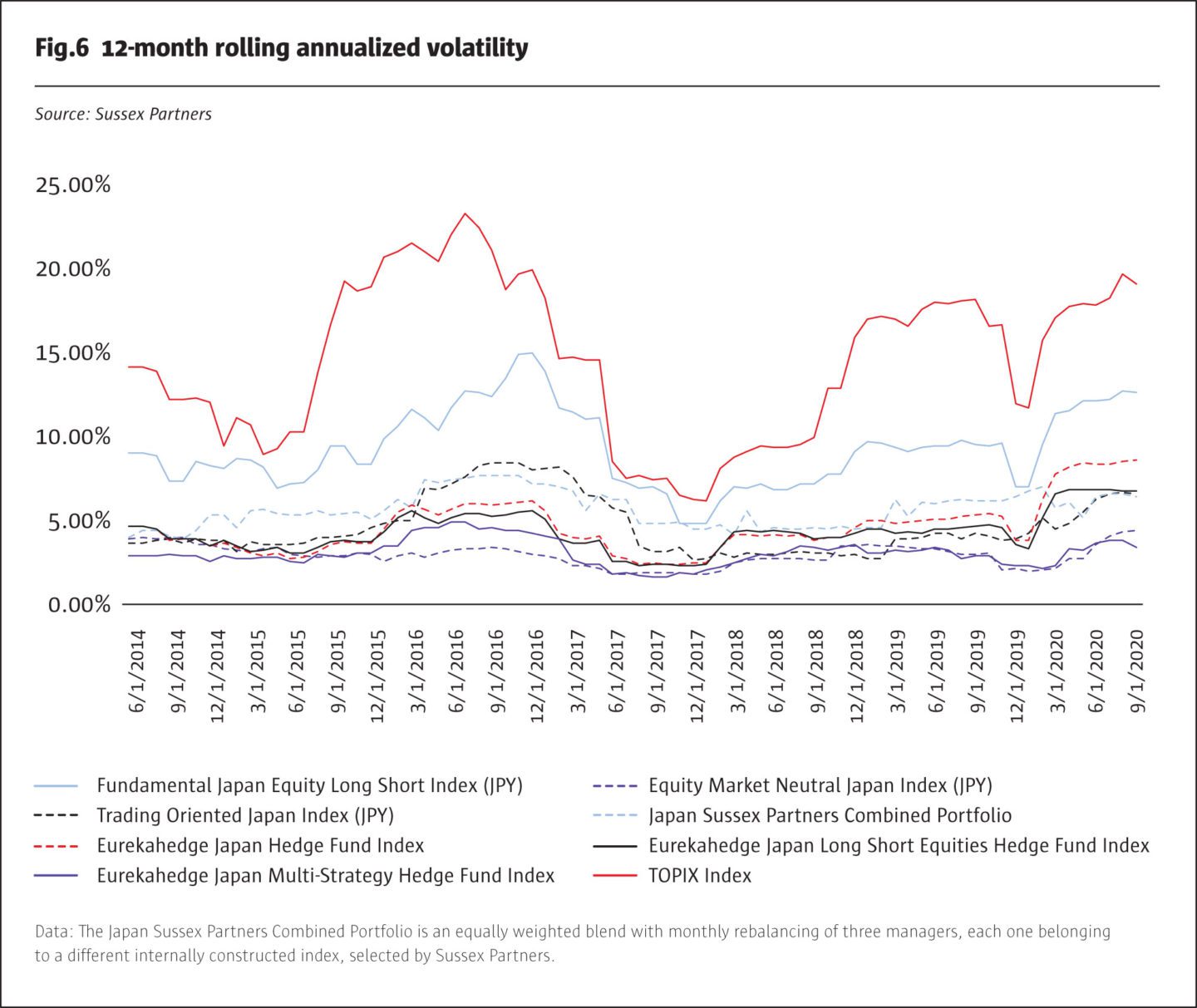

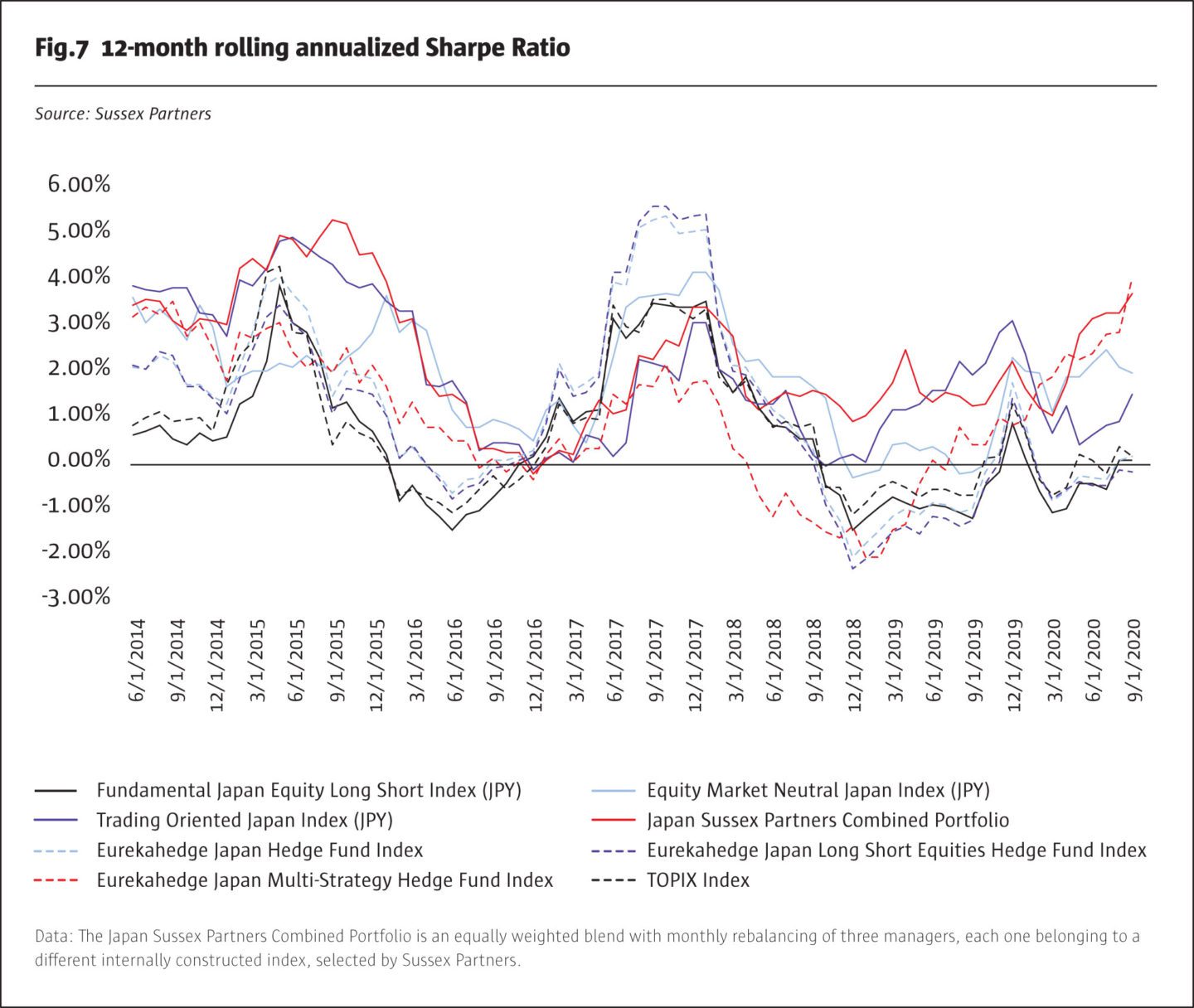

This then leads one back to the question of how best to approach investing in Japanese hedge funds? Should investors try and identify one manager, and hold that manager for the long term? Should they try and time the market and switch between strategies, or are they better served with a (small) portfolio of different funds instead? While holding one manager may make sense, as long as investors are able and willing to tolerate periods of underperformance (Fig.5), market timing is notoriously difficult and probably not appropriate but for the most sophisticated and experienced investors in Japanese hedge funds. The divergence in performance among managers and investment styles, the low correlation, and the lack of capacity, all seem to suggest added value from the construction of multi-manager portfolios. Combining fundamental long/short managers (higher volatility, and suffer in environments of significant market interventions which lead to divergences from fundamentals, but also tend to be better at capturing up trends in markets), with trading oriented managers (steady albeit lower returns, but with few manager options/scarce capacity), as well as market neutral managers (lower returns than trading oriented managers, lowest rolling annualized volatility of any other sub group of managers, readily available capacity/manager options), should allow investor to create an all-weather portfolio.

Figures 6 and 7 show what such a portfolio, based on a somewhat carefully selected set of managers, could look like in terms of rolling annualized volatility and Sharpe ratio. Additionally, this approach benefits from the ability to deploy meaningful amounts of capital, as well as diversification of operational risk. It also removes the challenge market timing and provides different return drivers with little correlation to one another. The key to a successful portfolio of Japanese hedge funds ultimately lies in being able to combine bottom-up manager selection, based on granular research, with strategy diversification that allows investors not to have to engage in market timing, but instead allows different alpha streams to compound over time.

Footnotes

- Ghali, P (January 2020), ‘Japan Redux or where we currently See Opportunities’, The Hedge Fund Journal, Issue 146, available here.

- Y. Nakazono, M. Koga, T. Sugo, ‘Private Information and Analyst Coverage: Evidence from Firm Survey Data’, Bank of Japan Working Paper Series, October 2018, available here.

- Sussex Partners’ calculations based on data from Eurekahedge ‘Key Trends in Global Hedge Funds (October 2020)’, Eurekahedge, October 2020, available here and the Japan Exchange Group (Japan Exchange Group, 01 December 2020, available here)

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical